German-born, New York-based artist Jule Korneffel recently sat down with art historian, writer and curator Hector Campbell to discuss her move to New York and time at Hunter College, her art historical and academic influences, her physical painting process and her upcoming solo exhibition All that kale at the new Claas Reiss Gallery in Euston, London, which opens on Wednesday, November 4th.

Hector Campbell: You completed your undergraduate diploma at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, Germany, where you studied as a Meisterschüler (Masterstudent) of the acclaimed Danish painter Tal R. What sort of artwork were you making as an undergraduate student? And did you learn anything from studying under Tal R that still informs your practice today?

Jule Korneffel: Actually I transferred to Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, before that I studied for three years at the Hochschule der Bildenden Künste Dresden, a very traditional painting school. It was quite an academic drill, but very relevant to what I’m doing today. We studied the Old Masters in terms of how they built pictorial space and volume through colour. Even now my technique for employing negative space and my method of layering colour still derives from this. Both are major criteria in my work.

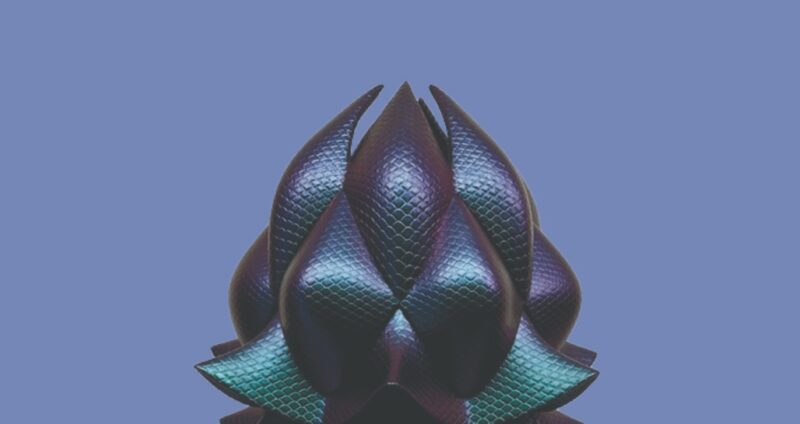

I decided to transfer to Düsseldorf because I was looking for a confrontation with the contemporary. Back then I was painting figuratively, the only time in my life I ever have, even though I’ve painted since age 2. I was mostly working with mythologically inspired themes, but my figures kept ‘dropping off’ from my paintings, and what remained were abstract patterns, some geometric, some reminiscent of florals. All these parts were figurative remnants, which I would paint over. My paintings were already going through a process of reduction, for which I was seeking a language.

I was very fortunate that Tal invited me to be in his class. It was just what I needed at the time. He supported, actually enforced, my loss of figuration, and sensitised me to the minimal and intuitive. His recurring question was: “How much less can a painting be, to be recognised as such?”

H.C: In 2018 you completed your M.F.A at Hunter College in New York, and presented for your thesis exhibition a series of abstract paintings that depicted text, numerals and circles set against striking monochromatic or patterned backgrounds. What led you to re-enter art education and pursue an M.F.A? And how did your practice evolve during your three years at Hunter College?

J.K: First, I have to clarify that those were not circles, ‘Balls’, ‘splotches’ or ‘circle-like shapes’ I can agree to, even though I think these elements in all of my paintings are (just) ‘marks’ in their essential meaning. I employ marks to define the painting, and while I define on canvas I do this simultaneously in my mind – I call this process ‘Internal landscaping’. The painting is a visualisation of my internal process. Marking is mapping my never-ending emotional flow; painting is a vehicle.

Mark-making was a key from my education at Hunter College. The term was new to me then, and it clicked. As far as I know, it is not a common term in German or European art history, and that is so interesting, as it tells you about cultural differences and how they apply to art history. Once I gained this missing key, my identity as a painter came together entirely. My paintings and I grew to a truly German/American compound over those three years.

American Abstraction, particularly the ‘New York School’, has always been a crucial part of my work. My decision to go to New York City and take the journey through another education derived out of my curiosity for learning. I wanted to study American Art in its actual environment and explore the New York art scene. I originally planned to stay for one year, as it was simply not imaginable at that moment to leave home for longer. But with my first step out of the subway on 23rd Street, my ‘love story’ with New York City began. We simply seem to be a fruitful match, I’ve been here six years now, and it has become my base, which includes my relationship with Spencer Brownstone Gallery, the New York art scene, and, of course, friends.

H.C: A recognisable trait of your vibrant, minimalist paintings is the exposure of previous layers of underpainting, revealed through a process of overlaying and filtering of colour. What role does the physical painting process play in your practice, as opposed to factors such as form and colour?

J.K: That process is physically tough, and is the most intuitive part of my work. Even if I draw from previous experience, each painting is a discovery of new, unknown territory. I’m normally working on approximately thirty paintings of all sizes at the same time. The panels lie on the floor, as the paint is too fluid for vertical application. Due to spatial limitations, the panels are piled up, get rotated within the piles, and then, if dry enough, get staggered on the walls. It’s a crazy procedure, and I even made extensions for a few brushes to reach more easily all over the floor. I have hardly any emotional, or spatial, distance from the paintings. I’m living them, it’s full chaos, the studio looks like a hot mess. But I’m following an internal logic that arises while working. I feel entirely absorbed into matter. Following this path takes me to a place out of matter – to meaning. I massage the paint in, and through adding and over-layering, the painting’s final form is cast.

The other, alternating step is just sitting and looking at the painting, trying to figure out what it is about. Looking at a painting is, as Mary Heilmann says, akin to watching a movie. Both the active and reflective parts of my practice are equal, and I can work and move between them as long as I know what the painting is about. The process is long, often a couple of years, sometimes a painting can remain untouched in my studio for months, but I only realise after months that it is done. I’m growing with my paintings, and sometimes they are ahead of me.

H.C: You’ve listed Agnes Martin and Mary Heilmann as two key art historical influences, the latter of whom you exhibited alongside in last years Mini Me Mary at Albada Jelgersma Gallery in Amsterdam. To what extent does art history, and the work of artists such as Martin and Heilmann, inform your own practice?

J.K: It’s still hard to believe that Renée Albada Jelgersma and I got to meet Mary Heilmann and that I showed with her! Her approach to imbuing personal, everyday experience into mostly geometric, abstract language has inspired me deeply. And the most important values I’ve received from Agnes Martin are her introspection, sensitivity, and persistence for taking the time the painting needed. Both painters believe in simplicity. Each, in her own way, links reductive and quite rigid compositions to human existence. They both seem absolutely dedicated to their work, and there seems to be no division between life and art. I’m impressed by their honesty and integrity. Agnes Martin is modesty, Mary Heilmann is directness. They speak their truth through painting.

I also maintain a close relationship to the Italian Renaissance, especially the Early Renaissance. Fra Angelico’s frescos, Botticelli’s colour and line, Giotto’s blue skies – looking at them feels like breathing fresh air. The works speak to me through their compassion. I find it interesting that this era, although so long ago, feels so close to me here and now. I wonder if this is because Humanism, which was re-introduced in a large scope back then, somehow speaks through these paintings.

There are more artists, movements and art historical references I could mention, most of them American, such as Cy Twombly or Minimalism, but it seems more important for this conversation to mention how I love to see nearly any exhibition. New York City’s art scene is very rich and diverse, I find it interesting to see and talk about what everyone is doing. I learn so much from this community I’ve grown into, and I simply love the people here. Cancellations due to the coronavirus pandemic have impacted this of course, but actually only transferred us to other mediums. It’s good to see though that galleries and museums are now reopened, and I’ve seen as many shows as I could recently. It is great that everyone seems to be back out there, and to run into each other again. New York’s scene still has its vibrancy, and I’m so glad to be part of it.

Authenticity and full dedication to the process drives my practice too. My longing for reduction originates from a deep care for bringing out an essence and letting go of what doesn’t really matter for the whole. My layering is a process of filtering, as in cleansing. I’d like to contribute to spaces where we can simply be again, places to reconnect and recharge. The current state of a global crisis has made me very sensitive to veracity. I’m inspired by and have great respect for anybody who shows humanity at this moment. We need people who have the courage to show up and contribute to the welfare of the entire planet. I believe we need to relearn making personal sacrifices in favour of the collective

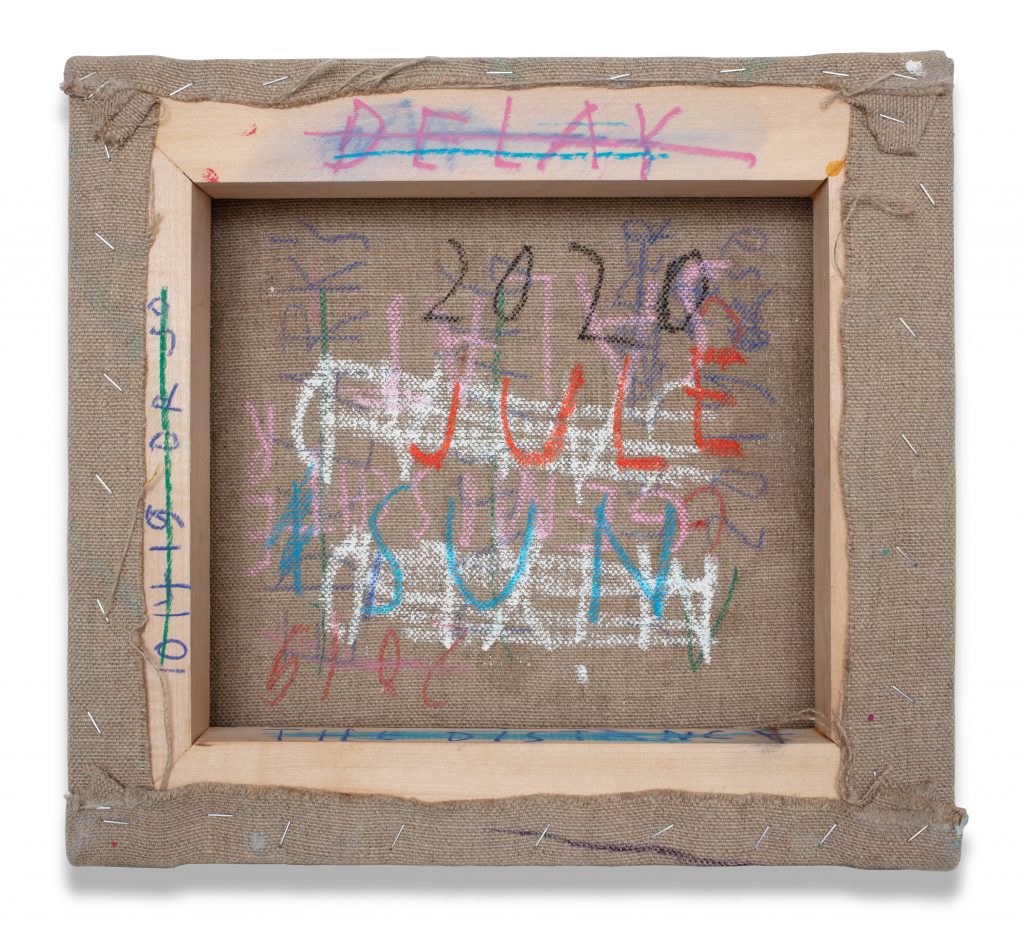

H.C: In previous exhibitions you’ve completed a number of wall murals, and have also been known to display paintings that can be viewed from the front and, unconventionally, the reverse. What effect do you hope experimental exhibiting methods such as these to have on the artwork’s audience?

J.K: I don’t think too much about the audience, my priority is that the work looks right. My paintings are containers of space and time, and as such, they relate to their environment. Although it is a subtle feature, the use of backs and sides underlines a painting’s ‘objecthood’. The backs carry written notes, the final title, and previous titles, while through the sides one can retrace the history of the layers of paint, akin to a rock formation, and perhaps some colour tests. This is subordinated additional information, and if space allows it is nice to occasionally display.

Each space requires something unique from the installation. Generally, I want any exhibition to be a sensual experience, as my paintings are. I hardly ever install the paintings on the same midline, it would look too firm. Instead, I seek for an installation which is as my paintings are: an open or floating form. I believe this best invites one into that sensual experience.

The first time I showed the back of a painting was in 2019 for my show Here comes trouble at Spencer Brownstone Gallery in New York. The piece Nacht was installed against the enormous glass window between exhibition space and backyard, facing its back to the exhibition and its front to the backyard. I also made a painting outside on the backyard wall. Together this wall painting, the outward-facing painting Nacht, and a third painting Sunset installed in the exhibition space, extended a line (like a bracket) of three different sky blues throughout the entire installation. This arrangement as well as the whole installation was a collaboration between me and the gallery (Spencer Brownstone and Jae Cho), and took shape as we worked and spent time in the space with the artworks over several days.

Because I can’t travel to London for this current exhibition, I used a model and installed dummy paintings on my studio walls to figure out the installation. I needed to feel ‘it’ all together to know what’s right. One rather larger painting is installed in between the front space and a walkthrough to the back space, and another is standing on the balustrade of the staircase. I hope that both interventions animate the viewer to move around in the spaces a lot. I don’t believe you can fully understand my paintings when sitting steadily in front of them, as they are not standing still either. It is also more fun to freely explore an exhibition. I like to encourage that.

H.C: Alongside the aforementioned influence of historic painters, you also maintain a keen interest in physics and have spoken before about your mathemetician father and the prevalence of mathematics in your childhood. In what ways do academic subjects such as these find there way into your artistic output?

J.K: What my father passed on to me is the understanding that math and science are rooted in intuition-driven discovery. My father lived in a world of abstract pattern and numbers, and we often communicated through equations and chess. As a child, I thought this is what you did, and, as colours have always been my world, I somehow – without consciously knowing – transferred numbers and names into my colour systems. I lost this ability when I began attending school, as my teachers made me use different colours for letters and numbers than those in my system, a time of great confusion!

Still, I retained my freedom for experiments and discovery. I’m actually interested in all different kind of sources, academic and non-academic. Right now my reading material includes painting techniques, anthropology, physics, metaphysics, alchemy, poetry, and fiction, and of course art history, to name but a few. I love researching, accumulating knowledge, and then filter it into paintings. Since the pandemic lockdown in March, I started to explore darkness. I have been reading, writing, and painting in almost equal parts. ‘A sun’, my most recent painting included in All that kale is the first painting to come out of this process.

I’m driven by light-hearted curiosity and an unrelenting joy for crossovers of any information and techniques. In this, I strive for the most comprehensive painterly outcome. I oftentimes think of my paintings as poetic formulas. I sometimes wonder if, above all, science is the most poetic subject. Referring to parts of Kurt Nassau’s and Isaac Newton’s colour theories, Victoria Finlay describes in her book Color her own sensual experience of this physical phenomenon – “I suddenly understood with my eyes and not just my mind how the phenomenon of colour is about vibrations and the emissions of energy.”*

H.C: Finally, your upcoming solo exhibition, ‘All that kale’, is both your debut UK solo exhibition and the inaugural exhibition at Claas Reiss in central London. Could you give us an insight into what to expect from the exhibition?

J.K: What to expect? Well, I feel incredibly lucky and grateful to have a solo show during a pandemic. I’m very honoured that Claas believes in my work and has me as the inaugural show of the gallery. I think we both put a lot of work and love into it. All I wish is for many people to enjoy seeing it.

Jule Korneffel’s debut London solo exhibition, All that kale, is the inaugural exhibition at Claas Reiss in Euston. It opens on Wednesday, November 4th, between 10:00 am and 8:00 pm, and will continue post-lockdown.

* Victoria Finlay, Color (New York: Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2004. first published 2002), p.6