Alison Jacques Gallery presents the first solo exhibition in Europe devoted to three generations of women artists living in Gee’s Bend, now known as Boykin, a remote black community situated on a U turn in the Alabama River. The exhibition provides a survey of quilts spanning over 90 years from the 1930s through to 2013 with some of the artists still living and working in Boykin today. The exhibition is organised in partnership with the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, a non-profit organisation dedicated to documenting, preserving, and promoting the contributions of African American artists of the South, and the cultural traditions in which they are rooted. The Foundation derives its name from a 1921 poem by Langston Hughes (1902 – 1967), the last line of which is: My soul has grown deep like the rivers. Our exhibition follows on from the inclusion of several Gee’s Bend artists in the UK museum show We Will Walk – Art and Resistance in the American South, Turner Contemporary, Margate (2020).

The geographic isolation of Boykin, and the tightly knit community within it, has created a unique environment for the women’s art community and their chosen language of quilting. The experimental processes and compositional language of these quilts has been passed through many generations of Gee’s Bend residents from grandmothers to mothers to daughters. The idea of handing down or passing on knowledge through generations of the same family is a key part of the artists work, and in the show we see members of the same family’s work exhibited side by side. A quilt by Aolar Mosely (1912 – 1999) from the 1950s is shown alongside her daughter Mary Lee Bendolph (b. 1935), and her granddaughter Essie Bendolph Pettway (b. 1956); both of whom continue to make work today. A quilt from the 1930s by Annie E. Pettway (1904 – 1972) is shown alongside her granddaughter Rita Mae Pettway (b. 1941). The familial lines of quilts illustrate a sense of community. Continuity is key with ideas passed on but uniquely interpreted within each generation. These quilts signify the artists personal pasts and hopes for the future, but also respect the culture from which they originated.

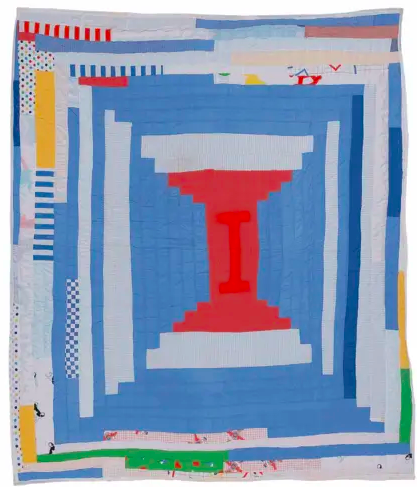

These quilted collages constitute a crucial chapter in the history of African American art; they are uninhibited by the norms of fine or folk art, often guided by a personal vision. Within the colourful and multi-layered works on show, we discover different quilting vocabularies and approaches to form and construction. Their use of symbols, asymmetry and bright colours refer back to African textiles and create a distinctive visual language which also recalls Modernist painting.

The artists refer to different types of quilting techniques, from Abstraction & Improvisation, Pattern & Geometry, Housetop & Bricklayer, Lazy Gal and Work Clothes. As Michael Kimmelman wrote in The New York Times review of Gee’s Bend work exhibited at The Whitney Museum of American Art (2002): The results, not incidentally, turn out to be some of the most miraculous works of modern art America has produced… These women, closely bound by family and custom (many Benders bear the slaveowner’s name, Pettway), spent their precious spare time—while not rearing children, chopping wood, hauling water and ploughing fields—splicing scraps of old cloth to make robust objects of amazingly refined, eccentric abstract designs.

Audio of some of the songs sung passed down through the generations of artists in Boykin are included as a backdrop to the show. Like quiltmaking, singing was an emancipatory act and an essential form of self-expression that sustained nearly all of the women of Gee’s Bend. In fact, singing and quiltmaking often went together, an outpouring of haunting gospel harmonies and ecstatic, spontaneous prayers amidst the endless rhythms of stitching.

The Gee’s Bend quilts were not originally created as art works but out of necessity. The very culture that these women were raised in taught them that everything had a use. When the nights became cold each winter, the women would use scraps of fabric and stitch a quilt to put on the beds of their children. The inspiration for this approach to construction came from daily practicalities, such as managing housing insulation, the residents using layers of paper found in newspapers or magazines to protect their families from the cold. In addition to their functional use, the quilts are often hung vertically indoors and outdoors on gates and clothes lines. It was, and still is, common practice for the quilt makers to ‘air out’ their quilts every spring providing members of the community an opportunity to study other’s methods and designs for inspiration the following winter.

The residents of Gee’s Bend are almost all descendants of the slaves working on the original Pettway plantation. The single road in and out of town was first paved in 1967, coinciding with the ferry service the community relied on, being suspended in an attempt by the nearby white community to stop the residents of Gee’s Bend registering to vote. During the Civil Rights Movement, the quilts from Gee’s Bend gained national recognition when the women formed the Freedom Quilting Bee collaborative, resulting in quilts being sold across the United States, which generated income returning to their community. In 1999, the Los Angeles Times featured Gee’s Bend artist Mary Lee Bendolph in the Pulitzer Prize-winning article Crossing Over, highlighting her and the community’s efforts to re-establish the ferry service across the Alabama River. In 2006, 39 years later, the ferry service was reinstated, with Mary Lee Bendolph now aged 85 years old, who exhibits a quilt from 1990 in this exhibition, still quilting today.

THE GEE’S BEND QUILTMAKERS Alison Jacques Gallery 26th November 2020 – 16th January 2021

The first major museum exhibition dedicated to The Quilts of Gee’s Bend was at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (2002). In 2006, the publication, Gee’s Bend: The Architecture of the Quilt premiered at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and that same year, the U.S. Postal Service issued ten commemorative stamps featuring images of Gee’s Bend quilts. More recently works were shown in History Refused to Die: Highlights from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation at the Metropolitan Museum, New York (2018). The quilts of Gee’s Bend are now in many prominent museum collections including Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia; Fine Arts Museums of San Francis- co, San Francisco; The Museum of Modern Art, New York; High Museum of Art, Atlanta and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.