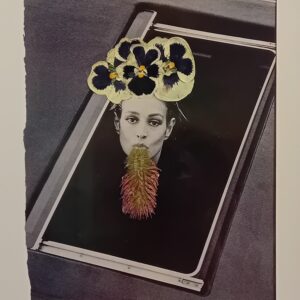

You can see a new work by Barbara Kruger, Untitled (Who?) (2020), installed on the facade of Sprüth Magers Los Angeles gallery now until mid-January. Visible from Wilshire Boulevard in the heart of the Miracle Mile arts district, a new work by Barbara Kruger, Untitled (Who?) (2020).

This work extends a long and celebrated history of public projects by Kruger across the world, including many in Los Angeles, that pose direct and pressing questions to viewers. In both English and Spanish, Kruger asks for example, in her recognizable bold, black-and-white font: “Who do you believe?” “Who do you hate?” “¿Quién es el que amas?” “Who do you hurt?” In the context of the imminent and divisive 2020 US Presidential Election, the ongoing struggles against systemic racism and a pandemic that has affected millions of Americans and others worldwide, such questions have never been more consequential.

Barbara Kruger Untitled (Who?), 2020 October 15, 2020–January 15, 2021 Sprüth Magers Los Angeles

About the Artist

Barbara Kruger (*1945) is an artist who works with pictures and words in the hopes of revealing and resisting socially ingrained assumptions about power: how it determines who lives and who dies, who is healed and who is housed, who speaks and who is silenced, who is visible and who is marginalized. Since the mid-1970s, she has juxtaposed her own texts with found images in her effort to expose the machinations of capitalism, politics and gender that often go unquestioned. Based in Los Angeles and New York, Kruger has been with the gallery since 1985, represented first by Galerie Monika Sprüth and later by Sprüth Magers.

The artist’s oeuvre spans photomontages and complex video and sound projects, as well as installations in the public realm. Frequently working outside the bounds of the museum or art gallery, Kruger has always managed to find new ways to reach the public, from traditional pictorial formats to vast architectural installations that transform the walls, ceilings and floors of entire spaces. Her works may appear in magazines and newspapers, the kind of light boxes usually reserved for advertising, T-shirts, posters, shopping bags, billboards, LED displays, displays on buses and in train stations, and on building facades.

Kruger’s texts—often in black or white lettering with brightly colored backgrounds, most often red—can become image elements in their own right. They take the form of evocative statements (“I shop therefore I am,” “Your body is a battleground,” “We don’t need another hero”), questions (“Do I have to give up me to be loved by you?”; “Who will write the history of tears?”) and suggestive declarations (“Put your money where your mouth is”; “You are not yourself”). When words pictures appear together, the texts dismantle the found image’s pictorial plane, making room for an abundance of echoes, effects, contradictions and implications.

Kruger’s emphatically visual conceptual practice draws on the aesthetics of graphic design and magazines (a field in which she briefly worked early in her career), 1970s punk posters and album covers. It plays with ideas informing the language-based conceptual art of the 1960s and 1970s, including those underpinning text and image works by artists such as John Baldessari, Jenny Holzer and Ed Ruscha, and it adds to the art historical legacy of German Dadaism and Soviet agitprop art by El Lissitzky and Aleksander Rodchenko. Perhaps the biggest difference between Kruger and her predecessors is her strategy of subversive mimicry: Kruger uses the dominant advertising media of late capitalist consumer society to criticize its patriarchal structures, its hierarchies and dynamics, effectively supplanting the innate purposes of these media with her own singular project.

Her works are political without trying to persuade viewers to adopt any particular system or ideology. Instead, they invoke and rattle positions viewers might take innately on account of their gender, social class, nationality, religion, or age, confronting them with often repressed feelings of powerlessness, ignorance, anger, fear, or greed. They exploit the immediacy of images and texts, and the unconscious and semi-conscious reactions evoked in the beholder, and they upend social stereotypes by forcing viewers to consider them in a new light. They are as seductive as successful advertising and as effective as propaganda. Ultimately Kruger subverts systems of cultural representation, turning it back on itself.