I met with artist Maria Pilotto on the occasion of her participation in Whatever it Takes (A Plus A gallery, Venice). Pilotto graduated from the Accademia di Belle Arti, Venice, one of the most prestigious Fine Arts schools of the country. She is the winner of several prizes and open calls, and her work has ben exhibited all around Italy. Last year, Pilotto took part in the famed collective show organised by Fondazione Bevilacqua La Masa, and she has been recently included in ‘Whatever it Takes’ at A plus A (Venice). During the past month, she was awarded an open studio in collaboration with Vulcano Agency. The final exhibition will be held next week.

Pilotto works primarily in painting, especially oil and watercolours, transforming family-memories in poetic works that ‘everybody can identify with’. Her works portray scenes of everyday life imbued in a rare intimacy. Most of the times, her landscapes are populated by human figures, sitting at fully set tables and dressed in elegant garments. Yet, their faces are never to be seen.

When did you decide to study painting?

I’ve always loved painting, since I was a child. I was very curious about colours, shapes, shadows. All my studies have been in Fine Arts institutions, where I balanced my passion for experimenting and my need to learn the fundaments of drawing. I’ve also worked at a goldsmith workshop, but I soon realised that was not my vocation – too laborious, slow, precise.

I guess you like the immediacy of watercolours, the fact that you can see the product immediately on the surface of the paper.

Exactly. With jewellery-making there’s a lot of rules to follow, a sequence of steps to respect. What I enjoyed was the drawing part – designing new jewels, creating new models.

When did you decide to study at the Accademia delle Belli Arti in Venice?

It was love at first sight! I remember walking down the hallway for the first time. It was mesmerising… there was art everywhere! I was used to just having my little desk where I could draw at school. There, every angle was covered in paintings, sculptures, installations. It felt like being inside of a huge shared-studio.

How was your experience there?

It was tough at first, I realised I had to sharpen up my language. My teacher told me ‘you have to define your style. Do anything, a simple portrait, but do it your way.’ I froze for a while but, eventually, this moment of confusion and halt helped me a lot. I understood what I wanted and how I wanted it to be done.

What kind of style did you develop?

I started experimenting a lot with photography, looking for different angles where to picture things. I would take tons of photos of trees from far below, imagining my self as a little kid in this gigantic landscape. Then, I transposed this passion for nature into painting. I would use the photo only as an initial source of inspiration, to then translate it into oil and watercolours.

Why the necessity to transform the it into something else? Why was the photo not an end product?

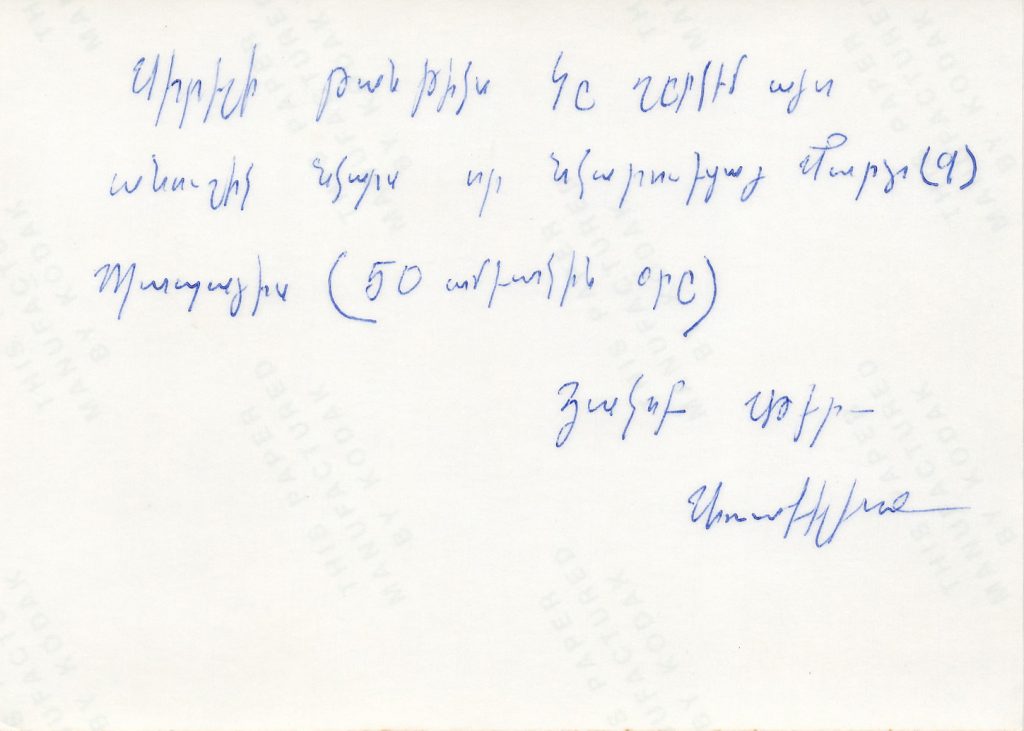

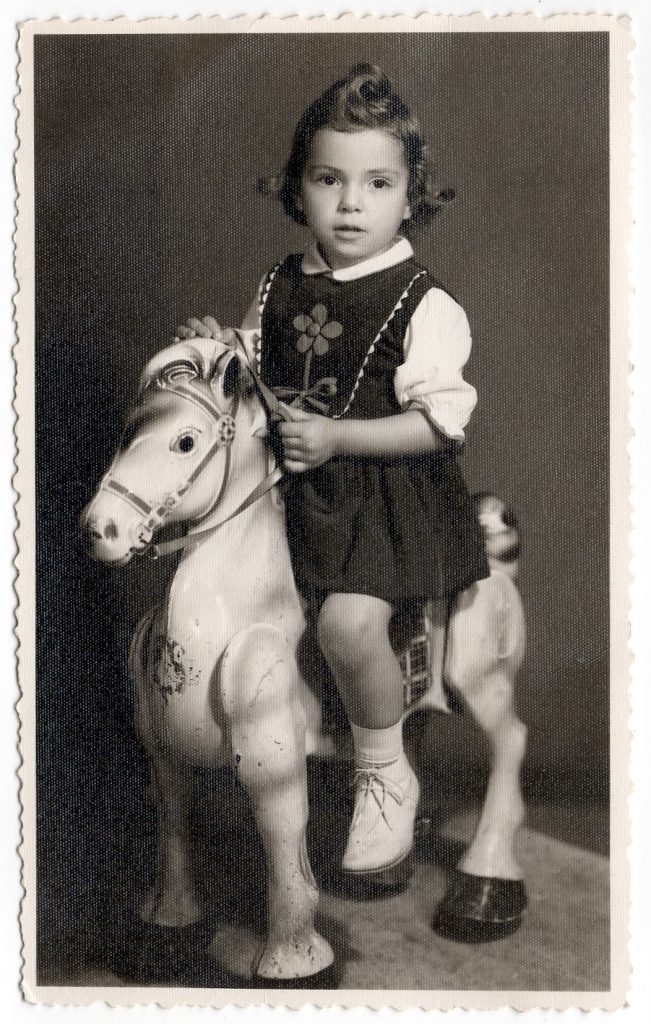

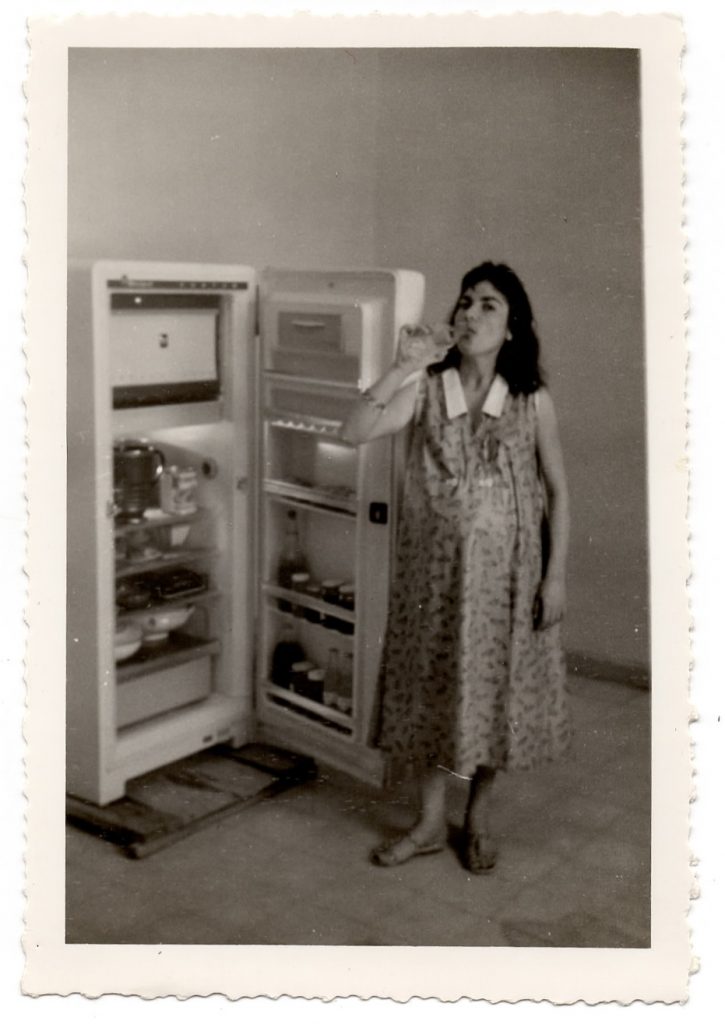

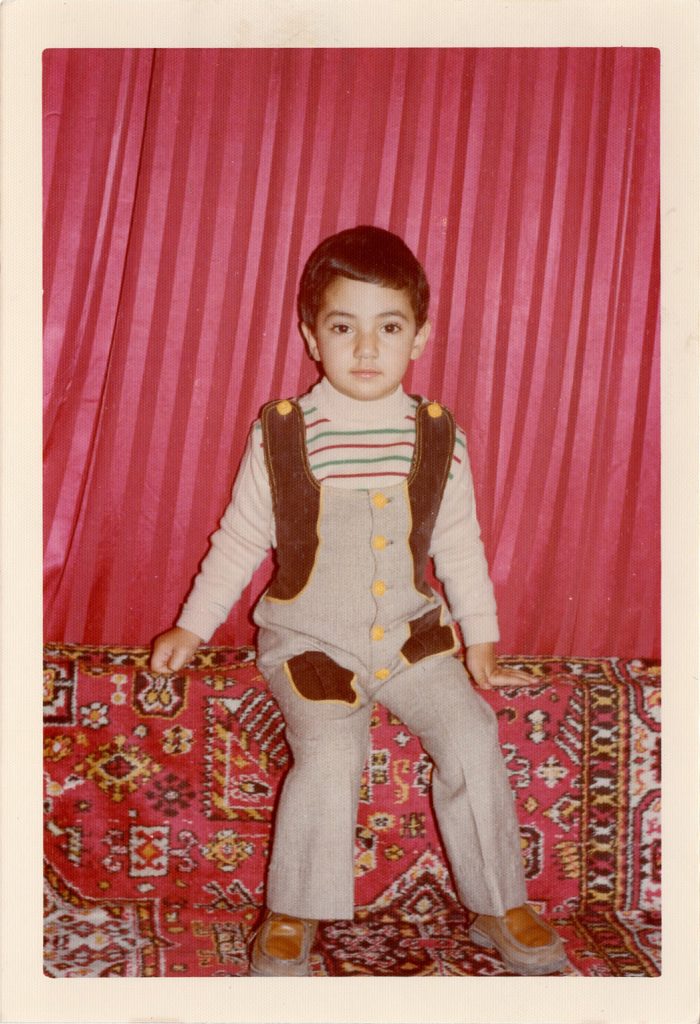

Most of the photos I use now come from a discovery I made a few years ago. My family has a very intricate story, with almost every person coming from a different part of the world. Since I was a child I would hear all these stories about my grandma’s festive lifestyle from Damascus; about my grandpa escaping from the Armenian genocide, or about the other grandpa born in Romania but having lived almost all his life in Puglia (South of Italy), out of several other places. One day, scavenging around the house, I found a box of old family photos. They all had such a rich history, it was fascinating! Many came with notes and short stories at the back, as if they were postcards.

How did you transposed this very emotional material into your work?

When I begun with this idea, I would only use the poses of my relatives for the final painting. They were just ghostly silhouettes cut out from their space and inserted into a new landscape. After a while, I started appreciating the incredible richness of details of the photographs— the sumptuous textiles of Damascus, the warm and vibrant colours of the houses, the flamboyant dresses. These photos shrined a whole culture inside! It became impossible not to integrate these particulars into my work.

The titles you use are quite evocative, sometimes funny, other mysterious. They tend to transport the spectator into a ‘parallel’ world, where we can only catch a glimpse of what is going on, while the actual references slip away.

That’s my aim: to create an enigmatic aura. Take ‘Carnevale Trani 1951’, for example. People might wonder what happened there in 1951, but the title simply refers to the photo that inspired it — a big carnival celebration! Behind this photo there was a note: ‘Carnevale Trani 1951’. I wanted to keep the intention of the photo in the painting, so the title became a memory of the original event. I often ask myself what will people think of these titles. Will they wonder who the people I portray are? What was going on? This makes me think of the work I exhibited at Bevilacqua La Masa, ‘Era forse la palma di Goethe?’ [Was That Goethe’s Palm Tree?]. I had just taken a photo of a palm tree and my mind wondered to the botanical garden in Padua were there’s this huge ‘Goethe’s palm tree’. Most probably the tree I photographed was not the poet’s one, but I just had fun inventing a narrative. It’s a pun, a game… but it makes things interesting.

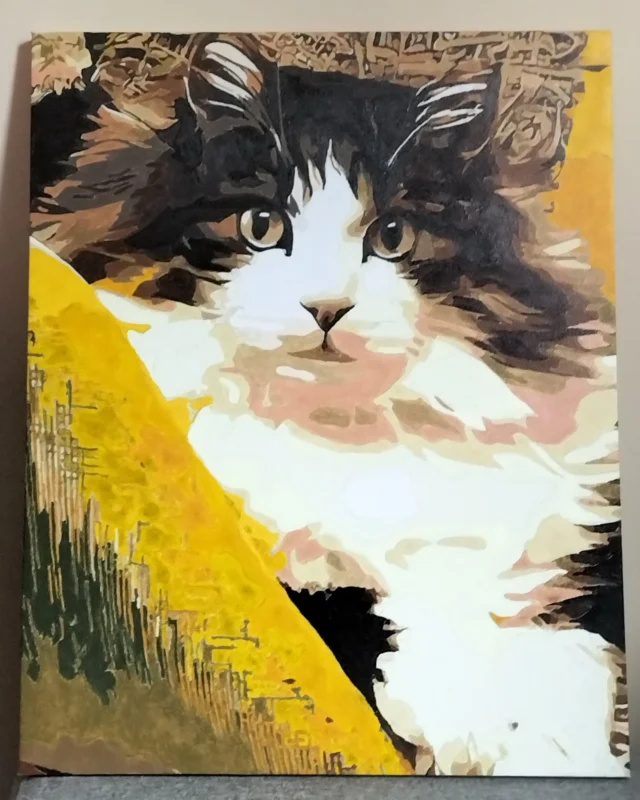

You often take the beholders into an intimate reality— an empty dining table, a child on her rocking horse; ‘Zia Lucia’s cake’ (La torta di zia Lucia). Yet you remove all somatic traits. Why?

I want people to enter an intimate moment, a familiar place. But I don’t want my personal memory to preclude anyone from identifying with a certain situation. At first I would make people the least invading as possible, drawing only silhouettes. Eventually, I started adding more details, but never enough to make my ‘sitters’ evident, singular people. I want beholders to recognise the situation without linking it necessarily to my own family. I want people to say ‘I had a similar moment’.

This is particularly evident in ‘Domenica = pasta al forno’ (Sunday = Oven-baked Pasta). There’s a fully set table, with flowers and all the cutlery, and yet there’s no people sitting at the table, nor can we see the over-baked pasta.

This work doesn’t refer to a one moment, but, rather, to a recurring event. Every Sunday we would make pasta al forno. In the photo I used as inspiration, the dish was not visible, but I though ‘if they photographed the table, it must have been a special occasion…. most probably a Sunday, with oven-baked pasta!’

Well… ‘Sunday lunch’ is sacred in Italy!

Yes! This reminds me of a story my grandma told me. Growing up in Puglia the whole family would go to the beach on a Sunday and have oven-baked pasta…. Not in any typical ‘beach-manner’! They would eat it on ceramic plates, demonstrating how important the Sunday meal is. ‘La torta di zia Lucia’ [Zia Lucia’s cake] is another instance of such culinary traditions and rituals. Aunt Lucia was famous for her cakes, and anytime she would make one the family would celebrate, no matter what. My mum used to tell me so many stories about this cake. One day I found a photo of my family reunited to eat a cake and I immediately understood it was aunt Lucia’s.

What made you decide to add some life to the protagonists of your paintings?

I got more and more into the richness of my family photos- the jewellery, the textiles, the embroideries. Oil painting, in particular, helped me analyse the picture even further. In oil you have to be slower, to work and rework the various layers. With every new layer I would add a detail, create more embellishment, more luxury.

Many photos are in black and white…. Why add colour in the final painting?

I like the dimension of colour. As Kandinsky said, every colour has a unique aura; every tonality gives away a different impression. That’s so true! I couldn’t renounce the emotivity of colour.

Have you ever worked in black & white?

I am exploring etching. At the Accademia my teacher encouraged me to turn my paintings into etchings, so I started experimenting with black and white. It was like going back to photography; you kind of use the same technique…. Now I am also developing coloured etchings, so I flow between the photographic technique, etchings, and colours.

What other techniques did you experiment with? Is there one that belongs to you the most?

I’ve worked with silk-screen printing as well. At first, as it was for etching, I thought it would have nothing to do with my recurring work. Again, I realised it’s all connected. In terms of a ‘favourite’ technique, I’d say it’s watercolours, probably because it’s where it all began.

You tend to work on a small scale with watercolour and oil painting…

Yes, especially with oil painting. I spend a lot of time working the image over and over again, adding a layer more every time. So with a small scale it’s easier and more immediate.

Furthermore, your works originate from small photographies — easy to handle, to touch, to look from quite close. Is your choice to create small works influenced by the intimate nature of your depictions?

I think so, the works would lose their intimacy. The richness of details would also get lost into the big picture. As the work gets bigger, it gets less defined, less precise. You stop appreciating the tiny details; the focus becomes the dimension of the painting, rather than the singular detail. I would get lost as well, not really knowing where to start and how to go on.

Did you stop photographing and using nature with time, entering more into the family house?

Not really, I actually keep working with both subjects, by uniting the landscape with the figures. I guess the recurring theme are the people that animate either the natural landscape or the house. Whenever I insert people into nature they become small figures into a gigantic landscape. So the world maintains its importance.