Trevor Paglen, CLOUD #865 Hough Circle Transform, Dye sublimation print; 156.53 cm x 126.05 cm. Installation view: Art in the Age of Anxiety, Sharjah Art Foundation, 2020. Courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery, New York. © Trevor Paglen. Photo: Danko Stjepanovic

On March 21, Art in the Age of Anxiety did not open as scheduled. Culminating a decade of research, the landmark group exhibition at Sharjah Art Foundation in the United Arab Emirates explores the manners and behaviours of a world reconfigured by digital technologies. Part II of our conversation with curator Omar Kholeif explores how the exhibition’s currents of bombardment, misinformation, emotion, secrecy and surveillance have flowed into the strange space of “hiatus” shaped by the Covid-19 pandemic. Read Part I, focussed on the exhibition, here.

Omar Kholeif is prolific. As a writer, curator and cultural historian he has led over 100 exhibitions, special projects and commissions globally, he has also authored and edited two dozen books and catalogues on contemporary art. Named as one of Apollo Magazine’s 40 under 40, he has held positions with the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Whitechapel Gallery, Cornerhouse and HOME, Manchester, and FACT Liverpool. Today, he is Director of Collections and Senior Curator at Sharjah Art Foundation, a boundary-pushing institution that has defined the cultural landscape of the Arab Gulf, and, particularly through its Biennial and March Meeting platform, shapes significant dialogues with artists and cultural thinkers from South Asia, the Arab world, and Africa.

Whether engaging with the politics of art in the Arab world or post-internet cultures, Kholeif’s books and exhibitions expose the latent structures of fast-paced social and economic change and hyper-mediated technological evolution. Though his pace of thought, work, writing, production is impressively relentless, as for everyone, the new realities of the pandemic have brought pause, cancellation, postponement.

Art in the Age of Anxiety is subject to this deferral, its themes exacerbated by the enforced closure. As lockdowns have quieted the velocity of frantic lives, we have found ourselves in a more static relation to the panic and anxiety prompted by our digital context; in stillness confrontation and inspection. So too the ideas of this as-yet-unseen exhibition are cast more starkly. The third of a loose ‘trilogy’ of exhibitions charting the shifts in context and consciousness shaped by digital and internet technologies, it follows the genealogical survey Electronic Superhighway (Whitechapel Gallery, 2016) and the more intimate reflections of I was Raised on the Internet (MCA Chicago, 2018). FAD spoke to Omar over Zoom, from London to Sharjah, in late-April.

The exhibition is open to the public from June 26 – September 26 2020, at Sharjah Art Foundation, UAE.

Trevor Paglen, ‘de Beauvoir’ (Even the Dead Are Not Safe), From ‘Even the Dead Are Not Safe’, 2019. Colourised eigenface, dye sublimation print; 126.05 x 126.05 cm. Installation view: Art in the Age of Anxiety, Sharjah Art Foundation, 2020. Courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery, New York. © Trevor Paglen. Photo: Danko Stjepanovic

A note on context: This is part II of a conversation that took place at the end of April, in the middle of lockdowns that had given a sense of extreme pause to life as it was being lived. In the past fortnight, though the pandemic still rages, global events have shifted us rapidly out of this experience of “hiatus”. As newsfeeds and news cycles mutate, they pattern a shifting consciousness, at the level of content, if not behaviour. The following conversation touches on the experience of pause in the context of technology and the lockdown. These thoughts are complicated by the urgent reminder of the imbalances that precipitate many of the pandemic’s tragedies. At the same time, cautious optimism might ask if current events will connect with experiences of the pandemic to resist a return to the “status quo”.

Omar Kholeif I was emailing with James Bridle the other day, who said he felt the obsession with trying to seem hyper-productive was especially strange right now, that this should be a moment for reflection – that’s what I want to take from this.

FAD Is it a case of reframing what “productivity” is? This process has felt a lot like mourning, a word that you used earlier. There’s a sense of grief. But grief includes processes of organising as well as emotion – sifting thoughts, feelings, reshaping life around loss, even efficient or bureaucratic modes of processing. I have found the most hope in the idea of a forced reckoning, being very honest about what we want to keep what we don’t need, what we’re willing to give up, what we must change.

There’s ritual, order, productivity in the processes of mourning. If those who have privileged space for reflection and hiatus could reorient themselves towards that mode of productivity, rather than the one of “keeping going”, perhaps there’s a possibility of disrupting a return to a faulty “status quo”. I think this is what I mean with regards to the “cancelled” future – perhaps it isn’t cancelled but postponed. What seemed relentless has given way to a vacuum of hiatus. The lifting of lockdowns suggests a need for progression–onwards–acceleration. It’s as if there is an impetus to keep moving, in case there is too much space to find alternatives. I wonder whether we can use this moment to reflect on what we want or need to keep?

Omar Kholeif One thing that we are doing at Sharjah Art Foundation is looking back at our archives – that’s probably why you saw that piece from last year’s March Meeting come up on your newsfeed. More broadly, I think it’s a good opportunity to go back to your own material, to the things that you have created and produced, to ideas you didn’t have time to follow through, to reflect “I was thinking this way then, I’m thinking this way now – maybe I have gotten better, maybe things aren’t as bad as they were. Maybe I want to return to those ideas?” I think that’s very important.

Now, it feels like the way of least resistance is through writing. I was on Zoom yesterday with Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, who I have worked with on shows that share common ground with Art in the Age of Anxiety. We collaborated in 2015 on a three-part exhibition called I Must First Apologise (2015), which was accompanied by the book The Rumours of the World: Rethinking Trust in the Age of the Internet. It was a whole project about spamming and scamming.

They said that, for them, as filmmakers and artists, the only way to get through this is to write. Expression (and by expression, we meant formulated expression, as opposed to something throw away like an Instagram selfie) holds the possibility for a thoughtful meditation on the situation. That can be our salvation. Through that, hopefully, we can find a creative outlet to express the ideas that we might not be able to explore for a long time to come through exhibitions.

FAD Has “the pandemic” changed everything, or has it just opened up a space to think, crystallised perspectives on things which were faulty, giving enough of a pause to gain some perspective? Either way, does it reframe all of our ideas? Allowing us to revisit what we had taken for granted, what we were unable to see clearly because of the sheer velocity of change, thought, noise, the bombardments of our hypermediated world. Are the ideas now necessarily going to be revisited and retold through the lens of this strange collective experience?

Omar Kholeif I don’t think we will have to cite “this” consistently, because I think a lot of our peer group, or people who work in our field, are aware of the context that has directly or indirectly led to this situation. Most notably, this notion of civic space has shifted into what I call a thickening, a textured digital sphere.

Digital space is proposing itself as another civic realm when clearly it is not – because most of the spaces that we use are owned by corporations, which are then owned by people who sell it on the stock market and make billions. And what do we make? How can that be our civic sphere? We have to find different ways of existing. I’m thinking about my own role in the world. I am asking myself whether curating is going to be a modus operandi for me forever or not; I don’t know – I would love it to be, but things might change.

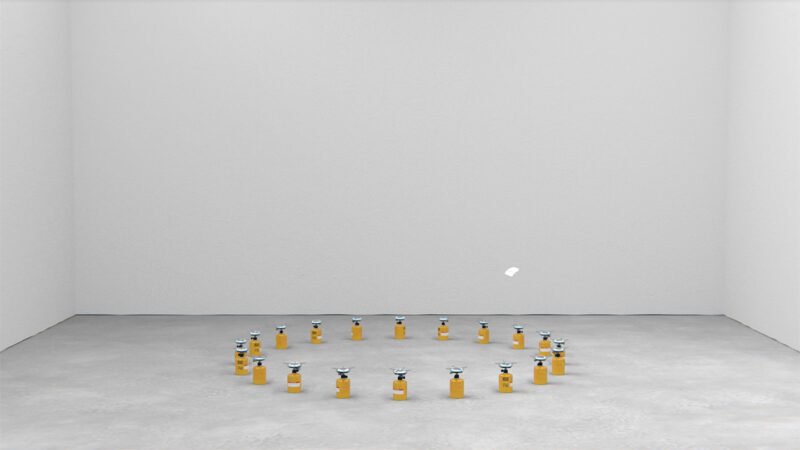

Katja Novitskova, ‘Pattern of Activation (Mutants)’ Digital print on aluminium, steel, cut-out display; dimensions variable. Installation view: Art in the Age of Anxiety, Sharjah Art Foundation, 2020. Courtesy of the artist and Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin. Photo: Danko Stjepanovic

Mark Westall When, or if, we come out of the “pandemic”, it’s going to be fundamentally different from when we started. Because of that change, would you re-consider doing a “chapter four” to the series of exhibitions, which began with Electronic Superhighway at the Whitechapel in 2016, followed by I Was Raised on the Internet at MCA Chicago in 2018, and concluding here in Sharjah?

Omar Kholeif No, absolutely not. It’s time to rethink the paradigm. I think this conversation has touched upon that very pointedly and appropriately, it’s time for something different. This is how I came to write Goodbye World – Looking at Art in the Digital Age. I was asked repeatedly to give talks about the Arab uprising in the digital age, about art and the Internet, about the “post-internet” moment. So, when I was a visiting professor at Hunter College, I just merged and distilled all my work into one long talk. At the end of the presentation, I said “Goodbye! Goodbye to all this research, I am done talking about this!” I put it into the world as a book as a way to close the chapter – I did not want to keep on doing talks about the same thing, it was no longer stimulating for me, nor did I believe that I was creating any new discourse. Likewise, here. If I did another, it wouldn’t be a “chapter four”, it would be a whole new beginning. And it might not be physical space, and it might not be online. I don’t know. But I think that the reality is that I’m craving a material culture. And I am craving a return to certain principles of thought; a sense that thought and thinking are respected.

We live in a world now where it’s all about how fast you respond… “Why didn’t you respond to that email?” “Why didn’t you get that up online?” “Why didn’t you write that?” On and on and on. That is not appropriate for the creative field. What we need now, I believe, is a reflective period, to pause and to return. It’s like we all need to go back to university for a bit – not the parties! The bit in the library.

FAD What you said about writing as process resonated. I am finding everyone’s capacity to TRY touching almost – that effort, that willingness to work with remnants or within confines, despite it all. I think it feeds into what you were saying about the need to rethink everything. It isn’t just about the number of opportunities, but also an opening up of new-old ways of approaching thought, to try ideas out. It’s so obvious it is almost trite, but I keep thinking about the origins of the word “essay”, “to try”. With writing, or whatever it is we’re capable of within limited confines, within disrupted conditions. It seems to me there are many very sincere efforts to think through new thoughts, or old thoughts with new patience and fresh perspective.

Omar Kholeif That’s what I think writing is; it’s trying. I don’t think any good writer sits down at their desk and thinks “I’m writing a great piece today”. We all know about the grit that it takes, the pain that goes into it. Essentially, when you want to make yourself proud, or someone else proud, you’re really trying. It really is about going through the process.

Eva & Franco Mattes, ‘What Has Been Seen’, 2017. Taxidermy cat, microwave oven, hard drives; 50 x 40 x 120 cm. Installation view: Art in the Age of Anxiety, Sharjah Art Foundation, 2020. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Danko Stjepanovic

FAD A lot of the ways that we worked digitally before the pandemic were about polished and composed presentation, so finessed it became perfunctory. We are suddenly in a place where we can only get to new thoughts, provide responses to the situation, in process. A moment characterised by stillness and limited horizons has catalysed a re-ordering of thought, with ideas and expectations “disturbed” into motion. This is an uncomfortable reminder of complacency, making me conscious of all the privilege inherent in finding possibility in this set of circumstances. Those thoughts are predicated on time, space, security, sanctuary, health – conditions so precarious and essential that they feel abundant and tentative simultaneously. Again, two feelings that tap into this sense of “trying”: we are compelled to try because of necessity; we feel inherently unsure of outcomes, so anything we do will be, at best, a provisional attempt. And of course – that secondary meaning of trying related to endurance – all of it is so much more taxing than when we didn’t have time to pause, to second guess ourselves.

Omar Kholeif What’s fascinating to me, and it enacts the ideas of the exhibition around shifting consciousness, is that I used to have an incredible memory. And I never had books “with” me, I would just write and write and quote and quote. But my memory has changed in the last five years, to the point that I don’t remember. And it’s difficult; writing the essay for this catalogue, I struggled! I did the opposite – I pulled every book from the shelf, rebought those I didn’t have to hand, to find one sentence!

But you can’t live your life trying to validate yourself for or through other people, which is what academia teaches you. This might also be an interesting shift in whatever “New World Order” we end up with on the other side – perhaps we won’t need to cite academics, but instead other kinds of people. I was talking to the managing editor for the Art in the Age of Anxiety book, Saira Ansari, and she pointed out to me that I had always intended to make the essay “lyrical” and that it was never going to be lyrical if this was my approach. She told me I had to just “go for it” – and I realised I never just go for it anymore.

It’s a universal problem, whatever you’re writing. It’s always a challenge, and it’s all about trying. I think all we can do now is try, all we can do now is hope. But that means taking agency, putting our voices into the world somehow – I believe that is done through writing. If not writing, it’s about platforms for critical thought, with an awareness of the presentation of that thought. If we don’t do that, I think we all might lose a bit of ourselves.

The exhibition was due to open on March 21. It is now due to open on March 26, and will run until September 26 at Sharjah Art Foundation, UAE. The Art in the Age of Anxiety Book is forthcoming from Mörel.

Trevor Paglen, CLOUD #135 Hough Lines (detail), 2019. Dye sublimation print; 126.92 x 169.23 cm. Installation view: Art in the Age of Anxiety, Sharjah Art Foundation, 2020. Courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery, New York. © Trevor Paglen. Photo: Danko Stjepanovic