On July 6th, Vanmechelen’s most awaited project yet “LABIOMISTA” opened to the public. The “new-age zoo” saw over 4,000 visitors on its first weekend. I was lucky enough to be invited for a sneak peek and a chat with Vanmechelen before its opening.

Koen Vanmechelen in “The Battery” bird enclosure, Photo:Kate McIlwee

For more than 20 years Koen Vanmechelen has been creating work that explores the connections between art, science and community. He follows the philosophy that art has a vital role in enhancing our understanding of current issues, developing solutions and creating sustainable diverse communities. LABIOMISTA, meaning “the mix of life”, is a multi-faceted project bringing together the vital threads of Vanmechelen’s work, seeking new opportunities for collaboration and creating a space for dialogue on challenging social issues. The 60-acre site features a park called The Cosmopolitan Culture Park, full of animal enclosures, the artist’ studio “The Battery”, entrance and meeting building “The Ark”, a gallery space “The Villa”, and an open-air pavilion “LabOvo”.

It was over 30 degrees when I arrived in Genk on Monday morning. I was staying in a hotel right across from the station I had arrived at. The hotel was embellished with a dark stone throughout and dimly lit, its appearance and its name “Carbon”, instantly identified Genk’s cultural history as being an old mining city. Unlike other Flemish cities, Genk does not spread out from a church steeple – it spills out of three mines. After the mines, the motor industry became the new sustainable economic and social model for Genk. These industries have attracted quite the unique melting pot of cultures. There are currently over 100 nationalities in a mere population of 66,000 people. With so many nationalities, conflict and tension have been a part of Genk’s history. Vanmechelen has collaborated with the city of Genk to transform one of the central mines, ironically already once transformed into a zoo, into LABIOMISTA to celebrate the uniqueness of the city and its inhabitants, and to showcase his work. The collaboration between Vanmechelen and the city of Genk makes a lot of sense, seeing as diversity and coshaping communities have been at the centre of his most recent work – such as The Cosmopolitan Chicken Project, the Planetary Community Chicken, and The SOTWA Project, amongst others. Vanmechelen has also collaborated with Detroit, similarly devastated by an extinct automata industry and struggling with conflicting communities.

“As an artist, I connect with a city with a ‘wounded history’: a city with a past in which identities such as the mines, or Ford, have disappeared. There is room for other structures, for transition. Here, we can start anew, with the energy that was once dug up from beneath the earth.”

Upon arrival of LABIOMISTA, you enter through “The Ark”, with obvious biblical connotations, is an instant indication to a motley crew of species, fertility and new beginnings. The dark brick of the building, designed by Mario Botta, cleverly signals the mining background of the site. A mythological figure sits on top of the building, acting as a guardian of the entrance. The figure’s head has been morphed into an egg. The egg is a clear symbol of fertility, and follows you around the whole site, reminding me of what Vanmechelen said; “It is a pregnant site.” The egg is also a nod to one of Vanmechelen’s most famous work; The Cosmopolitan Chicken Project.

The Cosmopolitan Chicken Project launched more than 2 decades ago. It is a crossbreeding program. The artist naturally breeds chickens from different countries, diversifying the flock’s gene pool. The project is a metaphor of the world’s diversity and to highlight weaknesses and vulnerabilities of establishing monocultures. A chicken represents the culture it is bred from. For example, the French chicken has a white body, blue legs and a red head, which is also the colours of the French flag. The Turkish chicken, Vanmechelen observed, made a similar sound to the call to prayer. Their traits are expressions and reflections of their culture. A culture that is co-shared and coshaped by animals as well as humans. Vanmechelen travels to these countries to discover these chickens and to continue cross-breeding. He even re-introduced the Cubalaya chicken in Cuba, which was thought to be mostly extinct. Vanmechelen brings his Cosmopolitan chicken into the gallery space with hens from that specific culture with the intent that they breed to diversify the flock. He brings science and biological discussion into the gallery space. Art has the potential to communicate this. He saw that his chickens were living longer, having more offspring, and not a lot of diseases. It was even confirmed by scientists that he was diversifying chickens. He believes that with larger diversity, there are more possibilities for survival.

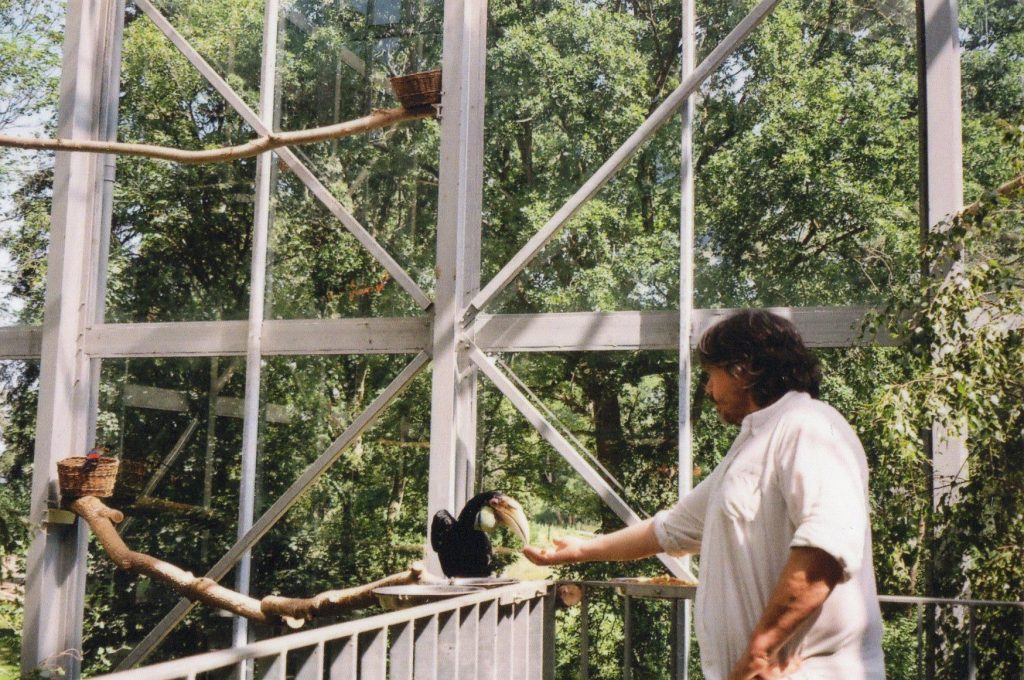

Koen Vanmechelen feeds the Hornbill Bird. Photo: Kate McIlwee

Koen Vanmechelen feeds the Hornbill Bird. Photo: Kate McIlwee

Vanmechelen began to be drawn towards struggling communities, economically and/or environmentally, which he saw as a result had weaker chickens. These areas had chickens often made weaker by industrial and factory farming processes as well. Commercial chickens have been bred to be more productive with the biggest chest as early on. Yet, are becoming weaker and weaker with more controlled environments. The chicken cannot survive in the wild anymore due to the sterile living conditions it has been bred in. It is bred to be consumed, rather than for strength and sustainability. No longer a natural evolution of the survival of the fittest, it is a capitalist evolution. One that does not benefit the chicken as a being in its own right – only the consumption of them. Vanmachelen decided to visit cultures and communities, such as Detroit, Zimbabwe and Ethiopia to breed his cosmopolitan chicken with their local commercial chickens. This is the Planetary Community Chicken. There is a balance between productivity and diversity, but also global and local – a new coproduced and co-benefitting balance that has the potential to strengthen the community.

In the meeting room of “The Ark” – the first building you enter in LABIOMISTA – the chairs have been covered with cow skin. The cow skin originating from the cows that Vanmechelen has gifted to the Mesai Tribes. The installation is part of Vanmechelen’s SOTWA-project, in which he has collaborated with African communities to strengthen and conserve biodiversity in local livestock. When the gifted bull has passed on, it is returned to Vanmechelen who then makes art from the bull. The art is sold for money to gift more bulls to the communities. It is a modern economical life cycle. I was informed that Vanmechelen never kills an animal for his art, only uses animals that have died a natural death.

“The Battery”, Photo: Kate McIlwee.

The artist’s studio, The Battery, energises the whole site. It is mostly private, but two huge greenhouses dissect the building and can be observed from outside. Split into two for meat-eating birds and fruit and seed eating birds. The space is for animals and for humans, and a balance between the predator and the prey. In-between waiting to see Vanmechelen I spent some time meeting the fruit and seed eating birds. Although dared to walk through the eagle enclosure, I decided against it. Used to birds flying away from me anytime I tried to communicate with them, and mangled pigeons trying to steal your food in London, I was blown away. Most specifically with the female Wreathed Hornbill from Southeast Asia and the Toco Toucan from East and South America. The hornbill reminded me of my dog, biting at my trouser leg to capture my attention, trying to steal my coffee mug, and eating from my hand. The toucan was shy, but always curious and always watching nearby. The two birds always seemed together and it seemed they had made their own version of a friendship in the greenhouse. At one point, teaming together to try to unravel the hose pipe in the hope that I or Vanmechelen would spray them with water. I had never shared a space so intimately with a bird before, and it made me realise how little I connect with birds in everyday life.

The Toucan in its enclosure,Photo: Kate McIlwee

The Hornbill, taken by Kate McIlwee

The paths leading towards the park dramatically wind and curve as to not disrupt the nature. They also forced me to slow down my walking speed, forcing me to take my time and take in the surroundings. The land had been devastated by the mining site and former zoo, however, the vegetation has begun to regrow naturally. The park houses a collection of domesticated creatures, animals that stand in between man and nature. Chickens are included in most if not all enclosures. Most notable, was the dromedary and ostrich enclosure. I was surprised the two could share the space so peacefully. The dromedaries often played the irritating younger sibling, by teasing and trying to gain a reaction out of the ostrich. The ostrich would calmly put its point across by fluttering its feathers in their direction.

Nomadland is an area developed by the neighbourhood of Zwartberg and Vanmechelen, it connects LABIOMISTA to the surrounding areas. There are allotment gardens identified by flags of orgin, picnic areas and clearings for events – Vanmechelen envisions it as an area of fertilisation and collective equality. He made a point of ensuring there would be no commercial café or restaurant built with LABIOMISTA as to not to take away from the neighbourhood’s developing commerce. Nomadland has the potential to open up as a market place for visitor and community. A space that is coproduced and co-beneficial. It is also a space in which people can meet and develop new ideas with ingredients from all over the world.

Vanmechelen’s work is not a static work of painting in a gallery, it is a living-art initiative or a living process which is both artistic and biological. When I asked him whether he saw himself as not only an artist, but also a farmer or a scientist, he only affirmed his status as an artist. He told me that only through the language of art, could he open-up difficult discussions and bring issues essential to our society into the public sphere. He is not the scientist, breeder, farmer, or the politician but creates or is the inspiration to change a mentality. LABIOMISTA is essentially that, a place where the arts will bring people together to experiment and speak about current issues.

Vanmechelen is aware of the politics of cross-breeding and has received backlash from putting animals into the museum and gallery space. His argument is that the conflict is already in our hands, and that he is trying to offer diverse solutions. As humans, there is constantly a need to simplify our surroundings and to understand complexity. Since he was a child, and his uncle gifted him with an incubator. He saw the small life force of an egg and the struggle to crack it – Vanmechelen has understood that you must find the right moment to crack the shell. Evolution and nature are complex and to simplify these he believes is very dangerous. As an artist, you use pain and experiences, and you speak them through the language of art. Vanmechelen believes that through his art, he is speaking the pain of our planet.

Koen Vanmechelen and Toucan in background. Taken by Kate McIlweeLABIOMISTA

Koen Vanmechelen and Toucan in background. Taken by Kate McIlweeLABIOMISTA

Marcel Habetslaan 60 3600 Genk (Belgium) labiomista.be

Special thanks to Goele Schoofs for her hospitality and kindness.

Image courtesy of Kate McIlwee