Marilyn Monroe might have crooned “diamonds were a girls best friend”. Yet, clearly she had not seen the treasury of an Indian prince. Christie’s London displayed a selection of magnificent jewelled objects which range from bejewelled cups and fly whisks to turban ornaments (sarpesh), necklaces, bracelets and rings covered in diamonds. The full collection of over four-hundred jewelled objects from the subcontinent is scheduled to auction in New York this June, after its global tour. I was filled with curiosity to see a selection of the collection of jewels in the ‘flesh’ as I entered Christie’s London.

I was drawn up the carpeted stairs into another carpeted room (with walls and floor covered in silk carpets for sale at an up-coming auction), into a dimly light circular room. In the centre a crescent of cabinets had been erected to contain the ‘magnificence’ of the Mughals and Maharajas of India. In the shadow behind this central crescent were placed more cabinets, and a few exquisite painted miniatures were hung depicting the bejewelled noble men of the subcontinent. My attention, however, as the curators had intended, was drawn to the central crescent and its well-lit cabinets.

An Art Deco emerald, sapphire and diamond belt buckle-brooch, Cartier. Octagonal step-cut emerald of 38.71 carats, buff-top calibré-cut sapphires and emeralds, old and single-cut diamonds, platinum and 18k white gold (French marks), 3½ in, 1922. Unsigned, partial maker’s mark (Atelier Renault), no. 0346, red Cartier case

Behind the glass I was confronted with a broad sarpesh (turban ornament) that looked like a tiara, with a broad band of five large cabochon diamonds set within a cluster of unevenly cut smaller diamonds, yet in fact it had once been worn at the base of a man’s turban. The cluster arrangement creates of diamonds set within gold foil creates an image of blossoming flowers. From the largest central flower-face rises a tower of diamonds framed on either side by a parallel row of diamonds set at an angle on thin gold stalks. The tower curves to the left like a feather and tappers in a larger diamond flanked by two smaller triangular stones. From this hangs a large roughly cut and highly polished red stone. Nine large spinels hang along the bottom of the band. The largest central spinel is helpfully inscribed with the names, titles and dates of its former royal owners, Shah Jahan and his father Jahangir. These Mughal Emperor’s were renowned for their lavish tastes and exceptional collection of gemstones. This detail is both a dynastic declaration and a touching reminder of the sentimental value of jewellery.

I turned next to the next cabinet and saw a large diamond necklace, which had once belonged to the Nizam of Hyderabad (1850-75). The seven large triangular diamonds larger than a 50p coin were set into an intricate web of gold wire inlaid with smaller bud shaped diamonds. From the centre hung an eighth large diamond surrounded by a band of smaller diamonds. The stones were cut flat, with few facets, as if they were slices water. The shallowness of the stones would allow the broad collar necklace to lie closely against the wearer’s chest. I tried to image the man who had once worn this necklace. Was he a vain dandy like the foppish princes of the French court in their powdered wigs and high-heeled buckled shoes? It seemed more likely that the Nizam of Hyderabad wore such a dazzling necklace simply as a Englishman in the 19th century had worn a tie.

Devant-de-Corsage brooch, 1912, Cartier. Pear brilliant-cut diamond of 34.08 carats, oval brilliant-cut diamond of 23.55 carats, modified marquise brilliant-cut diamond of 6.51 carats, heart modified brilliant-cut diamond of 3.54 carats, lily-of-the-valley old-cut diamond links, platinum and 18k white gold (French marks), 7½ in, 1912. Signed Cartier

Turning my head to take in the other cabinets filled with egg sized emeralds and rubies the larger than golf-ball suspended between a strands of pearls, I felt a shiver run down my spine. It felt like snooping into your grandmothers forbidden jewellery box. The incredible size and superb quality of the stones were breath-taking. In the knowledge that these pieces were made for, and worn by, men I tried to remove my childhood notion that jewellery is the luxury of women, and that diamonds are not just a girls best friend. From the enormous scale of the bangles, necklaces and rings on display, one would be forgiven for imagining the deceased Maharajahs bedecked like Paul Ru’s drag-race contestants, however the subcontinent cultivated very different attitudes to gender and jewellery in the 16-17th centuries compared to the West. Diamonds, emeralds, pearls, and the Mughal’s beloved Balas rubies and spinels, were not gendered as exclusively feminine. The imperial harem was as richly bejewelled as the Emperor.

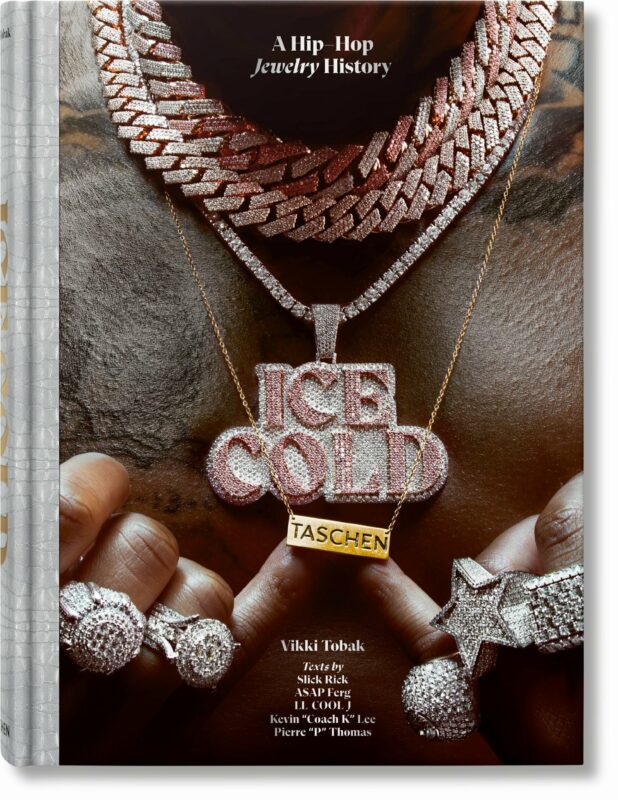

Jewellery really is genderless. I reflected that more and more of my male friends were searching for silver rings or piercing their ears just as the powerful Mughal general Asaf Khan who was depicted in a small miniature hung by the door. Men’s jewellery is a fast growing market today. In September 2018 the New York Times published an article reflecting on the impact of social media on men’s fashion. Cynthia Sakai, a Japanese jeweller noted that although men today “don’t look at fashion magazine, they do look at Instagram”. Moreover, the research company NPD Group declared: “Millennials are driving men’s jewellery sales, generating half of the growth, followed by Gen Z and Gen X”. In fact, their had been a 22% increase in global sales of men’s luxury jewellery between 2012 and 2017 according to Euromonitor International. As evident from the display at Christie’s it was clear that Mughals and Maharajah’s were one step ahead and that diamonds are not just a girls best friend.

Diamonds aren’t just a girl’s best friend… as visible in ‘Maharajas and Mughal Magnificence – A collection of Extraordinary Treasures.’ Christie’s, London: 26th-30th April 2019

Further reading: professionaljeweller.com/in-depth-an-analysis-of-the-mens-jewellery-market/

nytimes.com/jewelry-mens-rings.html

Buy Art jewellery and watches from The MET here

for more info: https://thehollywoodmirror.com/