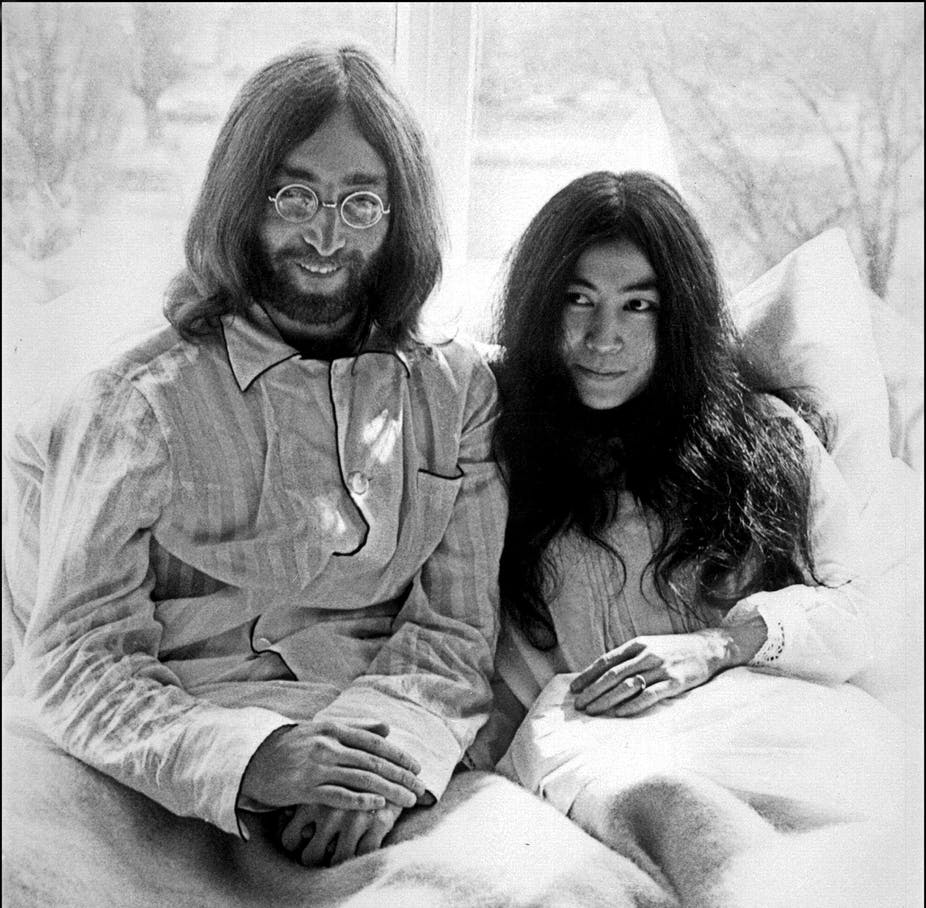

John Lennon and Yoko Ono at the Hilton Hotel, Amsterdam, in 1969. EPA-EFE

Fifty years ago the Beatles released a single that sold over 8m copies – their highest selling 45rpm – Hey Jude. While Hey Jude made the greater impression, it was the B-side – Revolution – in which John Lennon addressed the global political upheaval of 1968 that has the more interesting story. Rare as it was for a pop song to address politics, the message in Revolution – which I outline in my book – attracted fierce resentment within the radical left before re-appearing in 1987 in one of the most seminal and ground breaking advertisements ever made.

Lennon wrote Revolution in India where the Beatles were meditating with the Maharishi while the Vietnam War and Chinese Cultural Revolution raged on. There was a major riot in London and Paris was brought to the brink of another revolution in May of that year.

Upon their return to London, the Beatles recorded the song with Lennon lying down to sound serene. In one line he sings: “You say you want a revolution … but if you’re talking about destruction, don’t you know that you can count me out.” And then, after a pause, he sings “in” (because he hadn’t made his mind up).

The rest of the band argued that the slow bluesy number was insufficiently commercial and so a faster, rockier version with distorted guitars needed to be re-recorded. Lennon reluctantly agreed, despite worrying that the political message would be more difficult to understand.

The first version (Revolution No. 1) appeared on the White Album, which was released later that year. The faster version, simply named Revolution, became the flipside to Hey Jude. A third version – Revolution No. 9 – was also included in the White Album. This was just a scramble of noise, static, and nonsensical phrases – though an early example of electronic mixing.

‘A lamentable petty bourgeois cry of fear’

Hey Jude was proclaimed as one of the Beatles’ best songs by the pop media which largely ignored Lennon’s more political offering. Yet the radical underground media railed, with Ramparts, the American literary and politcal journal, declaring “Revolution preaches counter-revolution”.

The New Left Review called it a “lamentable petty bourgeois cry of fear”, while the Village Voice wrote: “It is puritanical to expect musicians, or anyone else, to hew the proper line. But it is reasonable to request that they do not go out of their way to oppose it.” The Berkeley Barb sneered “Revolution sounds like the hawk plank adopted in the Chicago convention of the Democratic Death Party” and Black Dwarf dismissed the song as “no more revolutionary than Mrs. Dale’s Diary”.

Then in 1987 the song reappeared when the small advertising agency, Wieden+Kennedy, selected it for a Nike advert. It was the first major television advert Nike ever made. Wieden+Kennedy had previously attracted industry attention by featuring Miles Davis and Lou Reed in their adverts for Honda scooters and were becoming the agency that could deliver coups.

They also managed to secure Yoko Ono’s support. She explained that she didn’t “want to see John deified” nor for “John’s songs to be part of a cult of glorified martyrdom”. Instead she wanted his songs to be enjoyed by a “new generation” who would “make it part of their lives instead of a relic of the distant past”. So Revolution was licensed for a media campaign that cost between US$7m and US$10m.

The advert consisted of a jerky black and white, hand-held camera film that showed Nike athletes and ordinary people participating in a variety of sports at various levels of seriousness. It became a massive success. Nike sales doubled in two years and the advert’s theme of empowerment and transcendence with a personal philosophy of everyday life formed the basis of Nike’s branding for the following years and allowed them to dominate the newly emerging “sign economy” of brand culture (how brands started to gain value at a more cultural and aesthetic level).

By 1991, Nike held 29% of the global athletic shoe market and its sales had exceeded US$3 billion.

Selling out?

Yet the ad attracted controversy. Time magazine wrote:

Mark David Chapman killed him. But it took a couple of record execs, one sneaker company and a soul brother to turn him into a jingle writer.

The Chicago Tribune described the advert as “when rock idealism met cold-eyed greed” and the New Republic said: “The song had a meaning that Nike is destroying.”

Revolution, it seems, had apparently morphed from a “petty bourgeois cry of fear” into a sacred text, twisted and spoiled by a sneaker company. The most significant response was the US$15m lawsuit filed by Apple Records in an attempt to halt the commercial. Apple claimed that the advert used the Beatles “persona and good will” without permission. Reportedly, the action was settled out of court after the campaign had run its course, with Apple, EMI and Capitol agreeing that no Beatles version would ever be used again to sell products – truly the Nike Revolution was a one off.

Yet the critical attention generated by the advert appears to have had long term consequences for Nike. The negative press coverage on the brand accumulated, focusing on allegations of a “patriarchal culture” and labour abuses. The Nike Revolution advert did not just launch Nike into the stratosphere of brands. It singled it out for critical attention.

Yet it also helped normalise the everyday wearing of sports shoes.

Thirty years later, the everyday wearing of shoes designed for professional athletes is a normal part of consumer culture, demonstrating how society can live in the legacy of extraordinary marketing campaigns. Indeed, the possibility that so many people are wearing these shoes because Lennon, meditating in Rishikesh, decided to address the politics of 1968, is a reminder that the collision of culture and politics in the medium of advertising can often create the most unpredictable outcomes imaginable.![]()

Alan Bradshaw, Professor of Marketing, Royal Holloway

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.