Photographs of ‘Ein text passiert’ (1967) by Claus Bremer, designed and produced by Edward Wright with Roger Limbrick

This week, with Masterpiece, London Art Week and Mayfair Art Week, there was no shortage of events to see (yet I missed two of those three).

I started with a dose of concrete poetry at Chelsea Space where Gustavo Grandal Montero has curated ‘Astro-poems and vertical group exercises: Concrete poetry at CSA’. If we recall, it was my obsession with dsh at the Sotheby’s S2 opening that led me to find this show (I’m also harbouring the hope that Lisson will be taking its dsh show to London in the very near future – can someone please arrange?). Whilst I could not attend the original preview, the gallery opened its doors after hours following a panel discussion that took place at CSA.

Given Montero’s role as a librarian and researcher it came as no surprise that the show would be ripe with archival material. Upon entering we find ourselves surrounded by letters and postcards written by and to Edward Wright amongst others.

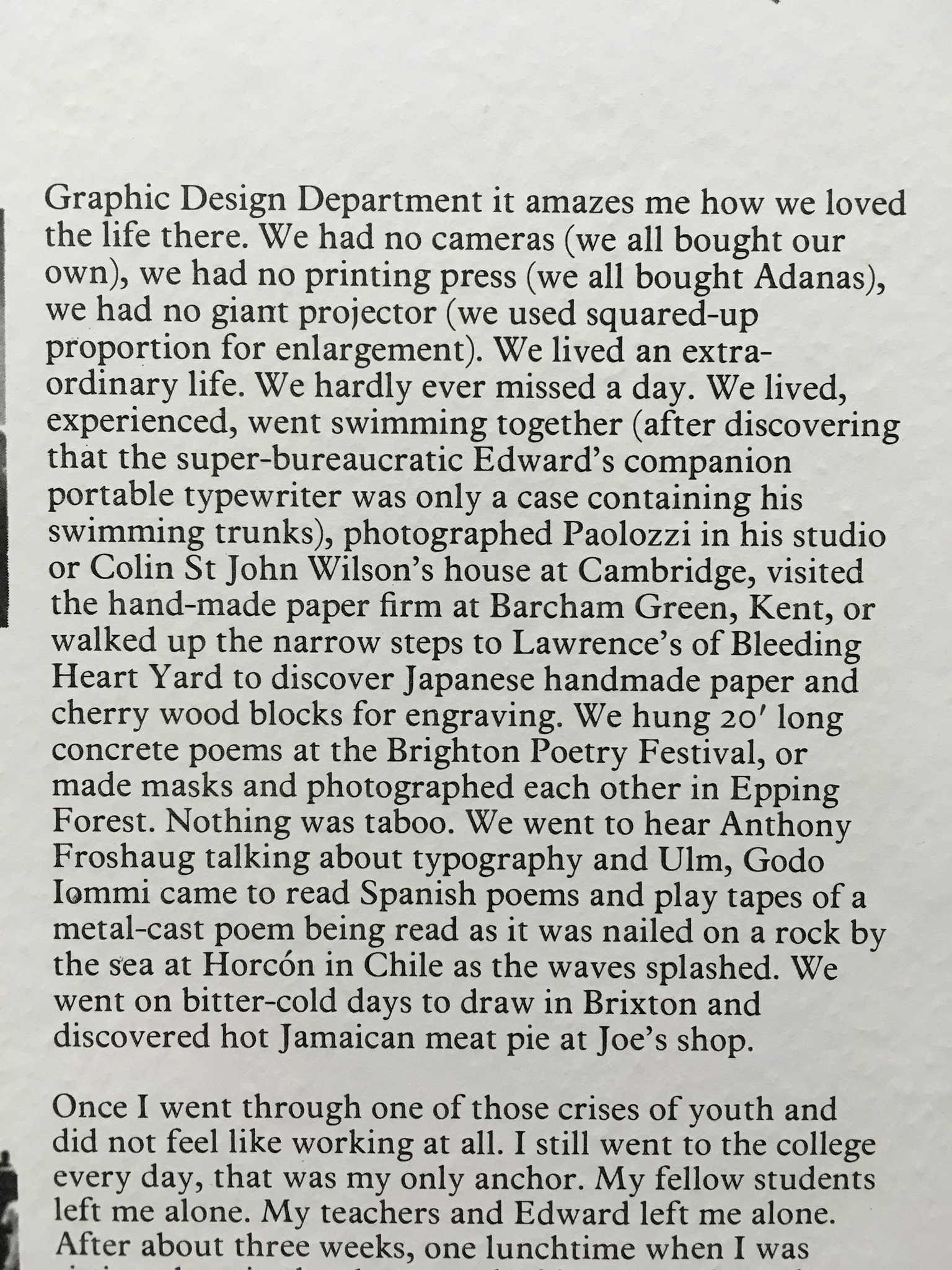

By way of brief introduction (although for those who can visit, do buy the publication as it contains essays and an interview between Montero and Stephen Bann – curator of the Concrete Poetry Exhibition in 1967) Edgar Wright was the head of graphics at CSA. He was extremely innovative in his ways of teaching. Perhaps the most endearing account is the one given here:

Facsimile of reading room materials

Whilst concrete poetry originated as a literary movement, appearing in Brazil and Germany for example in the mid-1950s, in which the typographical arrangement of words was intended to carry a stronger meaning than their sound or content, it soon became integrated with visual artists a decade later.

Of critical importance was the 1967 Concrete poetry exhibition at Brighton Festival (whose preparations are documented in the correspondence on display). Wright was responsible for creating the Flaxman font used to create the works presented, as well as the banner ‘Ein text passiert’. Curated by Stephen Bann, the show presented the different incarnations of concrete poetry that had developed in the last decade, crossing continents, schools and forms.

Chelsea Space illustrates this beautifully with Tom Edmonds’s works. Not only do we see the delicate, tear-like cascades of letters in his type tracks, his canvases and a collection of photographs documenting his shows and texts.

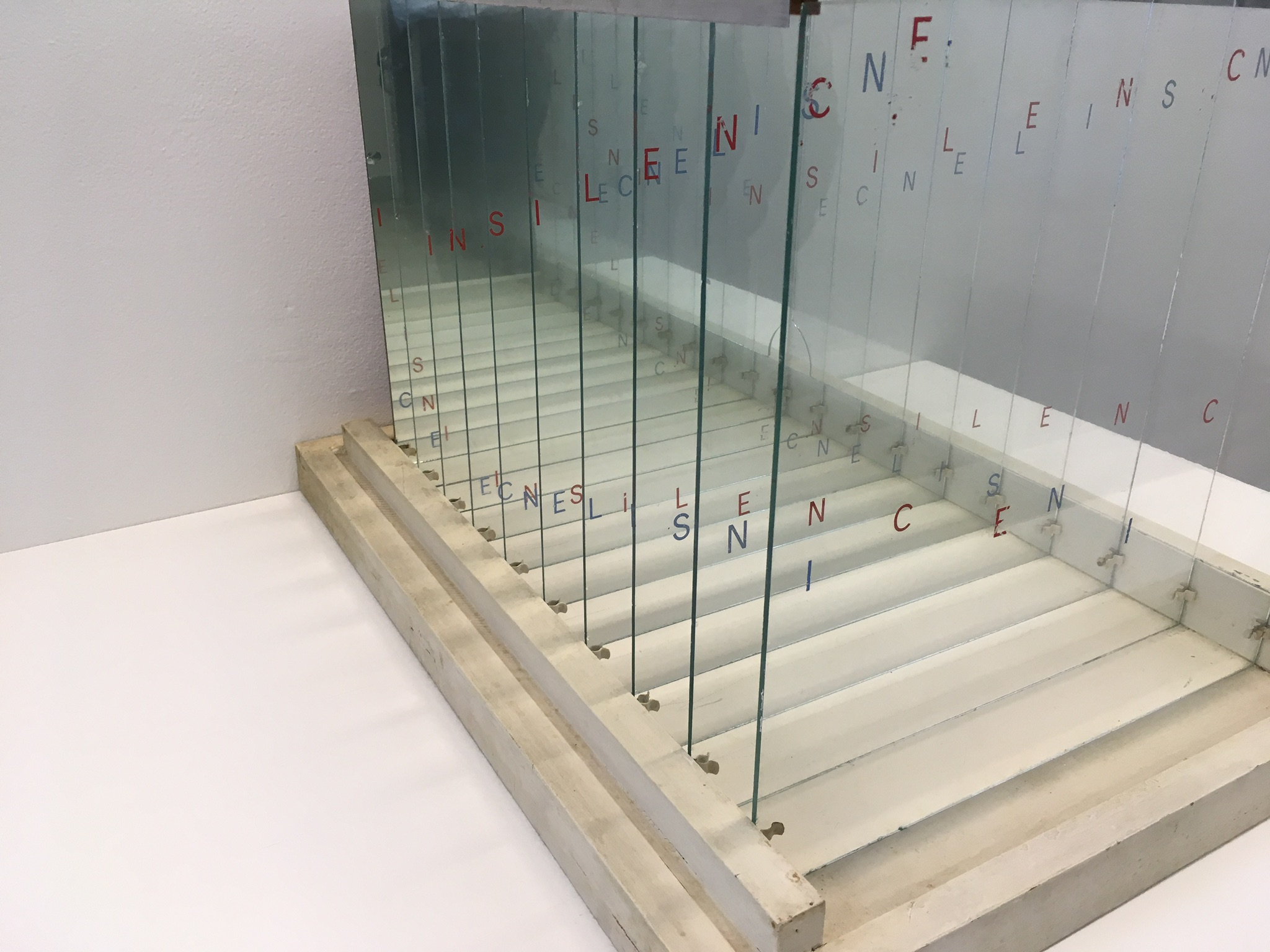

Tom Edmonds, In Silence

Importantly, Montero shows us Edmonds’s glass boxes – his astro-poems. In the main space a slide show flashes images of the works – whose location, in the majority of cases, is sadly unknown. The two we have on show are In Silence and Humbug Poem, both from 1968. The slight refraction, the letters floating, creating word constellations discerned, depending on our perspective, on clear glass or on an increasingly layered background.

I left Chelsea Space with an even greater fascination for concrete poetry and typography – and will no doubt proceed to search for even more archival material to satisfy my curiosity and would challenge anyone visiting not to find themselves similarly absorbed.

Hauser & Wirth’s Wunderkammer

I didn’t move too far as I headed over to Masterpiece London the following day. Further coverage on the fair can be found here. As it was my first time visiting, I was slightly lost and found myself near the hospital not knowing where the entrance was. It turns out that the fair was operating a golf buggy service so I hopped onto one and was driven to the doors where a bright red carpet marked our arrival.

Unlike Frieze, which appears to encourage more open stands and therefore increased communication between the galleries, Masterpiece feels very different. Granted it is held over a longer period of time, and I went on the second evening, yet each of the galleries had quite sternly delineated booths – meaning that although there was ample space to walk through – the setting felt slightly quieter and surprisingly more closed in. To its credit, it allows visitors – and most importantly buyers – to have calmer conversations with the galleries and spend more time browsing the works.

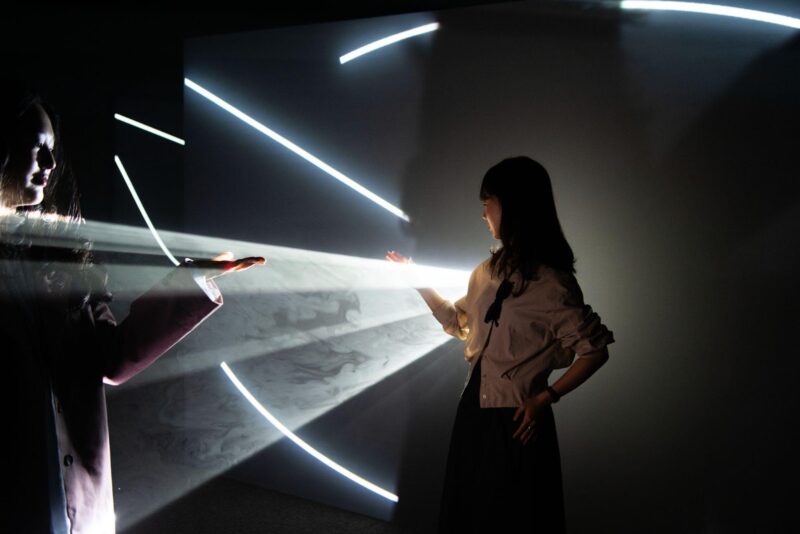

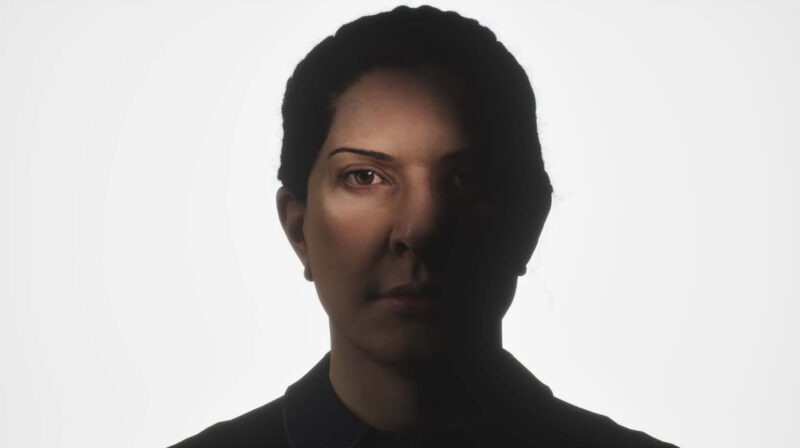

One of the first lessons we learnt, thankfully not first-hand, was not to inhale or open our mouths as we walked through Marina Abramovic’s installation. Those who tried to take a photo – eating her face? – were bitterly surprised when the fumes caused cough attacks. Ambramovic’s Five Stages of Maya Dance, a collaboration between Lisson and Factum Arte, greeted us and led us through to the main fair ground.

Larry Bell

I was eagerly looking for Larry Bell’s glass cube since I fell in love with his work at White Cube last year. Whilst the glass structure, with its misty density on its own is beautiful, I felt that its positioning in the corridor, with such low lighting, somewhat distracted from the gradients that would have otherwise been far more visible. It would have perhaps been better placed on the outer grounds – where the vibrant green of the grass would have added to its composition. In any event, Hauser, the gallery responsible for bringing it to Masterpiece, did have one of the best booths overall – with Louise Bourgeois’s naked cloth head, protected by a cloche, fast becoming a personal favourite.

Josef Albers, Homage to the Square (various)

Josef Albers featured prominently – with multiple iterations of his Homage to the Square on display. This was unsurprising given the amount of shows currently on (Guggenheim New York, Bilbao, Siena and Düsseldorf) focusing on him and Anni.

The range of works was incredible though, with Daniel Crouch Rare Books displaying a stunning 1247 antique Chinese stele engraved in stone mapping the stars, as well as M&L Fine Art’s showcase of works by Fontana and Boetti.

Chiharu Shiota, Turning World

We concluded our visit with a familiar scene, namely Blain Southern’s Chiharu Shiota whose Turning World, a complex arrangement of red string, netted the inside of the booth, much like it had the inside of the Church at YSP.

(If you laughed at the thought of me being driven to the red carpet in a golf cart, just know that there was a queue for them at the exit because they were that cool)

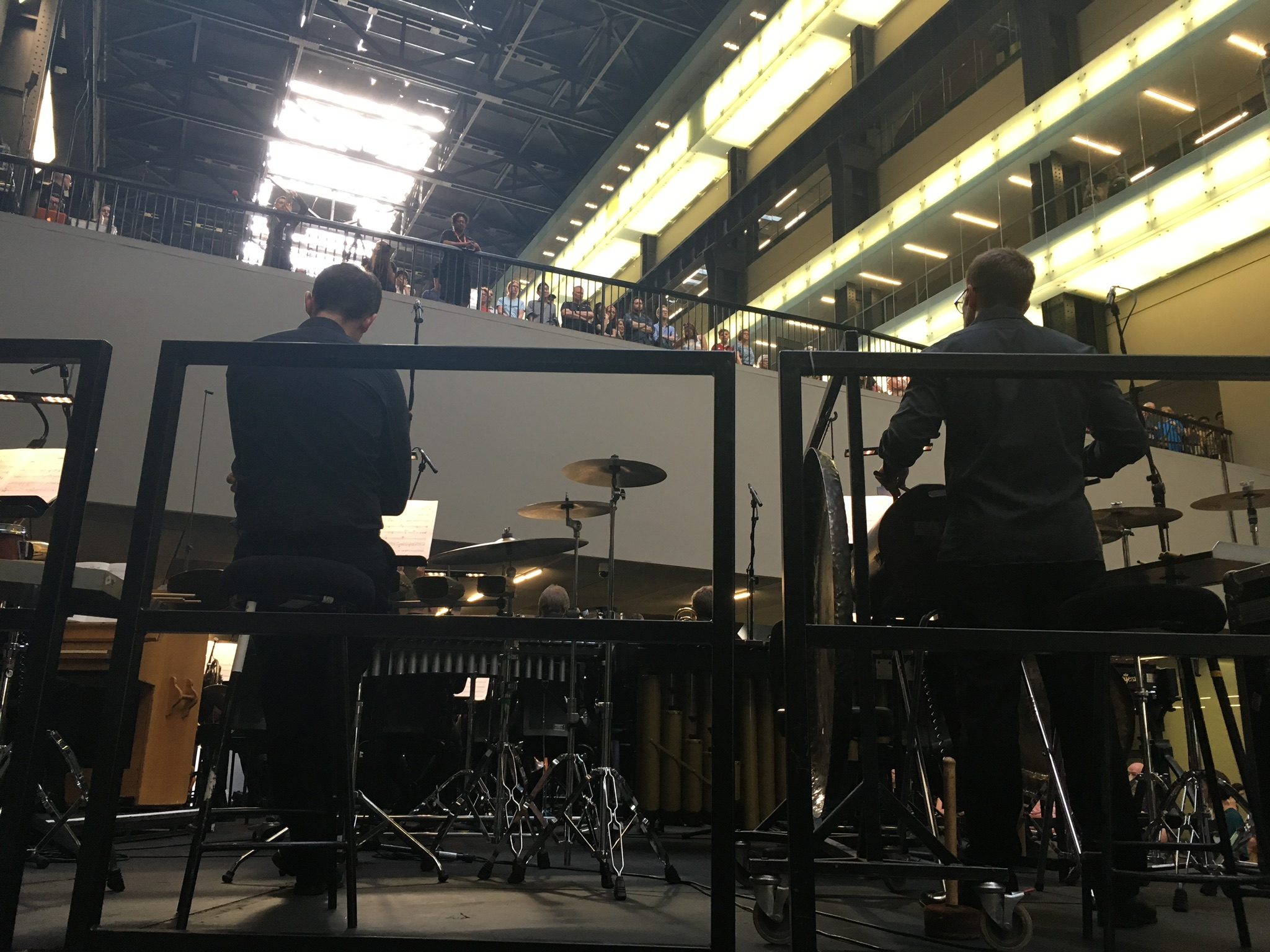

Finally on Saturday I found myself in the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern for Surround Sound – an afternoon concert by the London Symphony Orchestra.

Sir Simon Rattle conducting ‘Gruppen’

I certainly do not have the qualifications to critically evaluate the performance’s musical components and will not attempt to do so. We entered the Turbine Hall and found four different stages. Until the performance began we speculated as to which stage would be used first, whether the musicians would parachute down… We finally settled for the stage at the very back of the Hall and soon the LSO took its place on stage, with Sir Simon Rattle offering a wonderful introduction on the pieces – Messiaen’s Et excpecto resurrectionem mortuorum and Stockhausen’s Gruppen.

Messiaen himself believed that his composition ‘destines the work to vast spaces: churches, cathedrals and even out of doors and on high mountains’. With gongs, tam tams, bells and wind instruments – replicating chimes, death songs and mystical sounds – and a powerful concluding crescendo – the resurrection – the piece requires great acoustics. The Hall, as Sir Rattle noted, fulfilled both Messiaen’s aural and spacial expectations. As the tam tam oscillated, the reverberations crept high up towards the industrial shell above us, filling the space with sacred tones.

Duncan Ward and the LSO

The LSO then proceeded to leave the stage and populate the three remaining islands for Stockhausen’s Gruppen. This time Sir Rattle was joined by Matthias Pintscher and Duncan Ward, each conducting from a different stage. Stockhausen was interested in combining his knowledge of acoustics with electronic music. Originally he had intended to have a live orchestra play whilst electronic sounds on tape followed a different tempo. Eventually, he abandoned that iteration of the project for Gruppen.

We find ourselves navigating (quite literally, navigating through the crowd and around the three islands) through different textures of sounds, as we approach the ensembles. In doing so, we experience the piece differently at any one point. If this varied aural landscape weren’t enough, observing the three conductors interact with each other – as if playing an amicable game of tennis – was equally entrancing. Individual solo pieces invited quieter, more reflective moments, whilst the full combination of the three orchestras allowed us to witness the conductors come together – fusing genres and time periods.

LSO performing ‘Gruppen’ in the Turbine Hall

For those who were not in the Turbine Hall, or who were not there to see the performance from the ground floor, a recording is available on BBC Radio iPlayer on binaural sound.

Astro-poems and vertical group exercises: Concrete poetry at Chelsea School of Art is on at Chelsea Space until 13 July 2018.

Masterpiece London is on until 4 July 2018.

Surround Sound – London Symphony Orchestra was at Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall on 30 June 2018.