For the fourth exhibition in its space in Venice, Alberta Pane gallery presented the collective show Extended Architecture. For the exhibition, running until 29th September, Luciana Lamothe, Marie Lelouche and Esther Stocker created a series of works challenging the strict conventional limits of architectural definitions.

Lamothe, born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, envisages works suspended in between sculpture and performance. In this way, she challenges the steadfast borders that separates hard, static sculptures from their potential performability. No longer limited by their physical boundaries, her sculptures enter into an open dialogue with the human body. The three pieces displayed at Alberta Pane, for instance, whilst starting from the hardness of stainless steel, assume a soft, pliable shape, such as that of the human body.

The artist plays around the constraints imposed by defined and hard materials on shapes and definitions. Heavy materials almost lose their weight by remaining suspended in a ghostly manner on the ceiling. Due to the application of pressure to the solid structures, they get away with their stability, surrendering to gravity and ‘casually’ bending. Doing so, Lamothe is also putting under pressure the common knowledge of shape, structure, sculpture and architecture. The role of the viewer in this game of ambivalence is fundamental.

The iron formations hanging from the ceiling are not soulless congregations of materials, but are beings waiting to be activated. This performative quality of the pieces is twofold: they both engage with the space that surrounds them, and are activated by space itself and the spectators that live in it. The fact that all three works are untitled pushes further the idea that it is viewer who will have the last say; it is the viewer to whom the artworks are ultimately aimed at, and for.

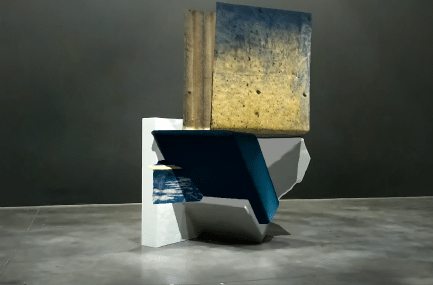

Marie Lelouche’s practice exploits new technologies to expand the field of action of art and imagination. In the middle of the central space of the gallery one of her Blind Sculptures stands in. It is a multifaceted block of high-density polystyrene, milled and white resin. This amorphous formation is but one of the thousand different shapes our mind can envisage. To help us experience the infinity of geometry and space, Lelouche provided each visitors with an audiovisual mobile device displaying a virtual scene scored by a sonic narration.

This i-pad like devices get activated only in the area surrounding the sculpture. Walking around the white polystyrene structure, a metallic voice will be accompanying you, while on the screen of the ‘i-pad’ three-dimensionally scanned shapes will keep rearranging on top and on the sides of the sculpture. The static, concrete sculpture placed in the middle of the room constantly assumes a new aspect under the influence of our own imagination and of the digital database of images.

Once more, the work is site specific and created specifically for this gallery. Although the actual sculpture that is exhibited has been showed already, any of the shapes that pop up on the audiovisual mobile device were thought for, and in, Alberta Pane’s space in Venice. Lelouche, in fact, came into the gallery two months before the opening of the exhibition to map out the space. She digitally memorised the walls, ceilings, architecture, and the general atmosphere of the room.

By recording the gallery in the cyber dimension the artist created an online archive inclusive of 300 shapes. These virtual structures will reveal themselves on the little screen, each time creating a different configuration and therefore rendering the experience unique. Not only site-specific, then, the work is also spectator-specific.

Although the starting point will be the white, irregular solid in the middle of the gallery for everyone, the actual experience of the space will be unique to each visitor. How the work will be perceived and how space itself will be experienced will depend on the sensitivity of the public, and not only on an automated reality. From an objective genesis, the artist engendered a subjective situation. This is contingent, as it keeps mutating and it depends not only on the virtual factor manipulated by Lelouche, but also on the specific personality of each spectator.

Surely, the technological side plays a fundamental role, as it clearly modifies of senses. But is it all negative? How much are we willing to give to technology? How much trust do we place in it? According to Lelouche, the use and understanding of new technologies is vital and should not be avoided but, rather, turned into an useful, research tool.

The artist, in fact, is strongly convinced that by visualising the new forms of our digital age we can also grasp the sense of our society. The development of shapes mirrors the evolvement of a community, and the only way to hold on is to keep up with technology. Nevertheless, the huge and seemingly irreversible impact that digital devices have on our brain is admittedly scary as well. Our senses are so modified by technology that virtual reality is starting to feel as real as the lived one. Perhaps Lelouche’s embrace of this mindset wants us to reflect on how far has technology gone and how it effects our thinking and living processes.

Derrida said that

‘the instant – the temporal mode of the sovereign operation – is not a full and unequalled point of presence: it slips in and out between two presences’

In the same way the structures scanned by Lelouche float in and out, up and down, side by side on the polystyrene sculpture. While virtual shapes marry the physical structure standing in the gallery, ephemeral thoughts match the concrete body movements of the spectators in the space. Tangible feelings, concrete perceptions, and feasible images keep intermixing in a time where the line between virtual and concrete increasingly blurs.

Esther Stocker’s work also converse and challenges the space and our perception of it. The artist took over the narrow, long, and brightly illuminated corridor that brings the spectators inside the wider space of the gallery. The work consists in a series of black, geometric shapes that create ever shifting conformations and phantasmagoric images as you walk pass them. The maze of seemingly regular structures disrupt the possibility of a unitary, univocal atmosphere.

It is exactly the unity, the mass, the uniformity that Stocker is trying to get away with. Although all the squares and rectangles are black and appear as part of an harmonic whole they are not perfect. How could they be, since they have to reflect reality? Furthermore, ‘perfection’ is by far a too personal matter to be considered as a universal constant.

As a matter of fact, each visitor will imagine in the addition and subjugation of the dark lines a diverse thing. Space will be experienced differently every time; the path will be walked in unstable motions, shifting and flowing with the ever-changing geometry of the work.

The grids the artist created take the idea of perfection and subjectivity a step further. The mathematical grids, all painted in feeble colours, present a sudden irregularity. At the climax of the work, the mathematical serenity is disrupted by something out of place. This ‘something’ is what makes the work the more interesting. This something is like the black sheep of the family, the genial outcast of the society, or simply the individual human being in her/his uniqueness.

The corridor at the entrance is made of cardboard, a poor and weak material turned into a structural, potent element. It’s filled with a constellation of empty or filled, black, geometric bodies, all in dialogue with each other. As 1 relates to 2, that then relates to 3 and so on, any of those forms is fundamental. Even the almost invisible cardboard squares make a difference. In spite of the fact that you can barely perceive them, they still matter. In the end, you still do perceive them. They matter just because of their being there; just because of their being.

In the disruption of the numerical consensus we should not read chaos, but an alternative order instead. There is a reason why things are as they are. They don’t just happen. In the same way, when in the corridor at the entrance we find a tiny, dense black square surrounded by huge geometric frames we should pay attention to the Lilliputian figure. Even if small in size, its importance in the grid is the same as any other structure. Balance (equally to society) is builded via a multiplication of forces, and any piece in the equation is fundamental.

To Esther, there is a strong correlation between grids and vision. Our field of vision is dominated by invisible grids, and our minds works through structured grids as well. The parallel between seeing and thinking also mirrors the way society works- via specific, rigid, exclusive rules. All that falls out from the mathematical perfection become invisible, or rather-not-seen.

What all works have in common is their desire to communicate with the city, its inhabitants and its visitors. To Alberta Pane, born in Venice, this is a vital element of any exhibition that takes part in her gallery in the floating city. The space she inaugurated last year is more than just another gallery. It is a second home, rather; a big, welcoming living room where artists and curators alike can experiment and go big. The huge room, accessible through a narrow corridor, is located in a residential area of Venice; probably one of the last tranquil oasis outside of the crazy business of hotels, bars, fake glass and carnival masks shops. It allows for a peaceful and stress-free environment where anyone can think out of the box and develop new ideas.