This week – besides almost losing my passport whilst Spring cleaning – I lay on a very comfortable pink carpet at 180 The Strand and then took a train to Wakefield to feel the density of Anthony McCall’s solid light sculptures and lie down on luscious green grass in the Yorkshire Sculpture Park.

Saturday marked the beginning of festival season in London and whilst many headed to Victoria Park I found myself around Temple for the launch party of Block Universe – the international performance art festival, now in its 4th edition, which will run across a variety of locations until 3 June.

Walking through 180’s corridor into the ground level room I could hear heavy music being played and, as I finally made my way in, saw a series of rigid strings, wrapped around the pillars, bathed in a red light. Unfortunately, as I was running from a concert at the Barbican, I missed the earlier performances and sets by Josephine Ada Chononye Chime, Rowdy SS and Rebecca Bellantoni. However I did catch Zoee and Rafal Zaiko and UNITI’s final set. The performers moved sinuously around the crowd, weaving their limbs through the space and electrifying it further. Upon leaving, as the thunderstorm rolled in and drenched me, all I could think of was returning to 180 the following day to see Maria Hassabi’s STAGING: Solo #2.

Maria Hassabi, STAGING: Solo #2

The image of Hassabi’s pink carpeted floor had haunted me for weeks prior to the launch. It appeared on the cover of frieze’s latest issue, on any Instagram feed, on FAD and almost every art publication and blog. Whilst the carpet itself was extremely enjoyable, Hassabi’s eight-hour live performance was entrancing. I decided to witness the closing hour and, as with any performance piece, although my gaze was primarily set on Oisin Monaghan – the young protagonist – observing the audience was also fascinating. In particular I followed the dynamic between Oisin, dressed in a bright patchwork outfit, whose colour blocks became more vibrant when contrasted to the overwhelming pink, and one of the invigilators. Occasionally collapsing on the floor diagonally from him, at other times on her phone, in other moments still crouched, holding her head in her hands fully focused on his movements, she felt connected to and part of the performance itself – as if she were the incarnation of all the viewers leaning across the four walls of the room. Oisin himself moved extremely slowly, occasionally woken up by very faint and transient piano keys, as imperceptible light shifts occurred throughout. There was something incredibly beautiful about the absorbing silence we offered to a body moving as closely towards stillness as possible – as if we were in a collective state of reflection.

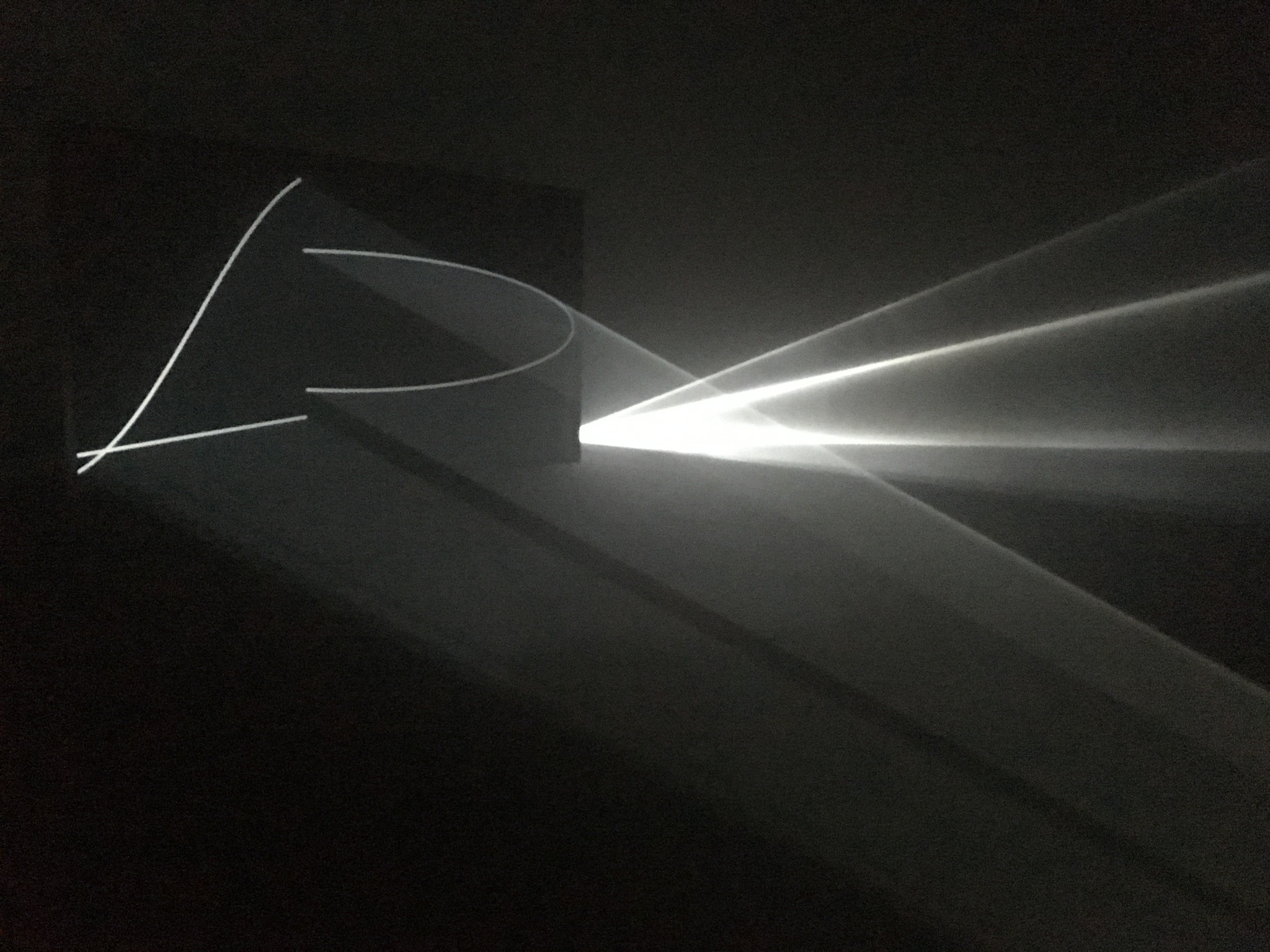

Anthony McCall, Leaving (With Two-Minute Silence)

Moving from one engrossing space to another in Wakefield’s Hepworth Gallery. I had been meaning to visit ever since I found out that Anthony McCall’s first major UK show would be held there. I had seen one of his single light installations at Spruth Magers earlier in the year and whilst walking through it was incredibly immersive, I was eager to see more. McCall was a key figure of the British avant-garde in the 1970s and sought to break the boundaries between film, art and sculpture.

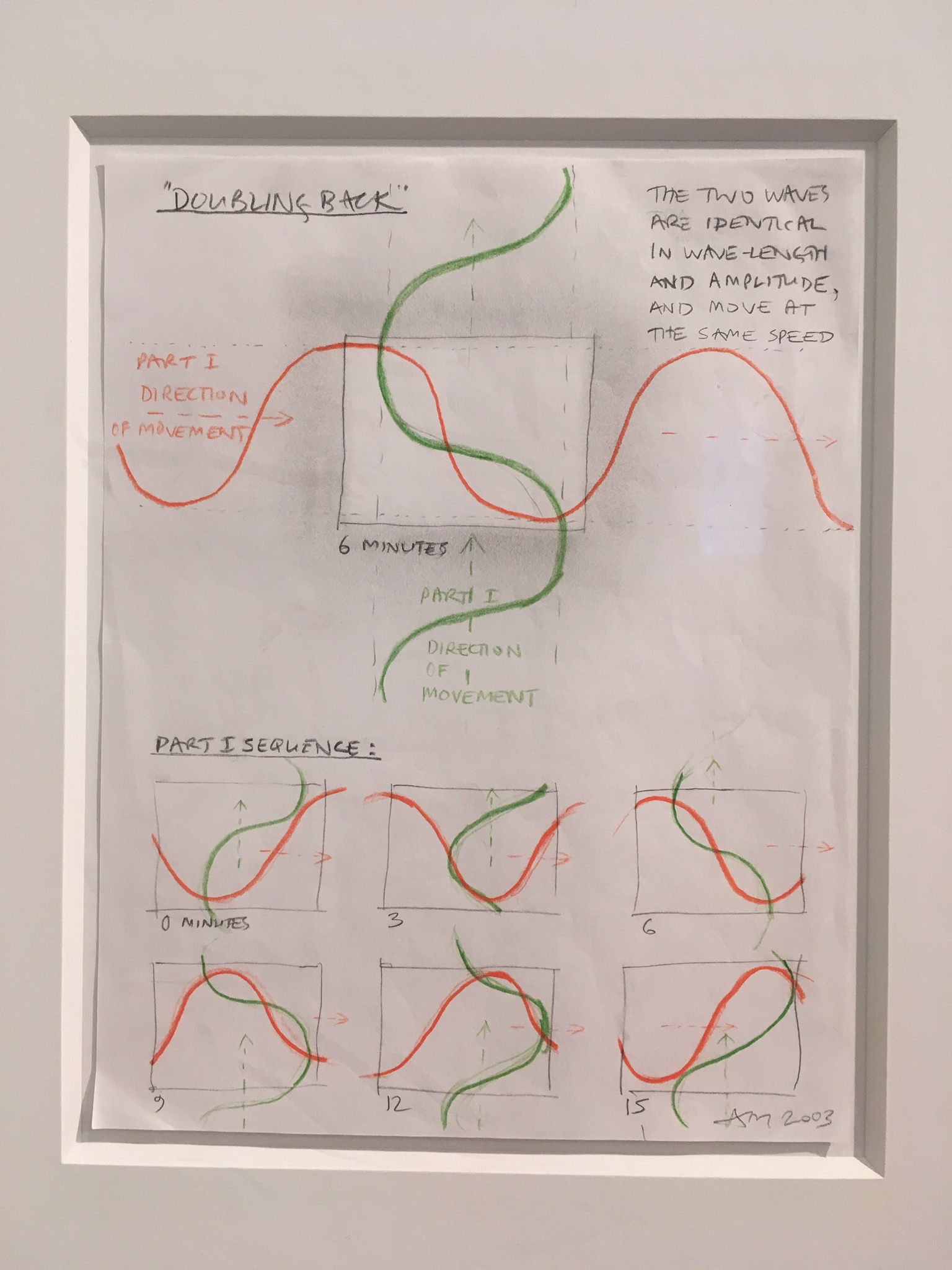

His light sculptures exist precisely as a blend of the three. His notebooks illustrate a meticulous approach to the physics of optics: he notes down the angles of the waves, their reflections, their tangent points and – most notably – what viewers should feel like when being enveloped by the dense beam.

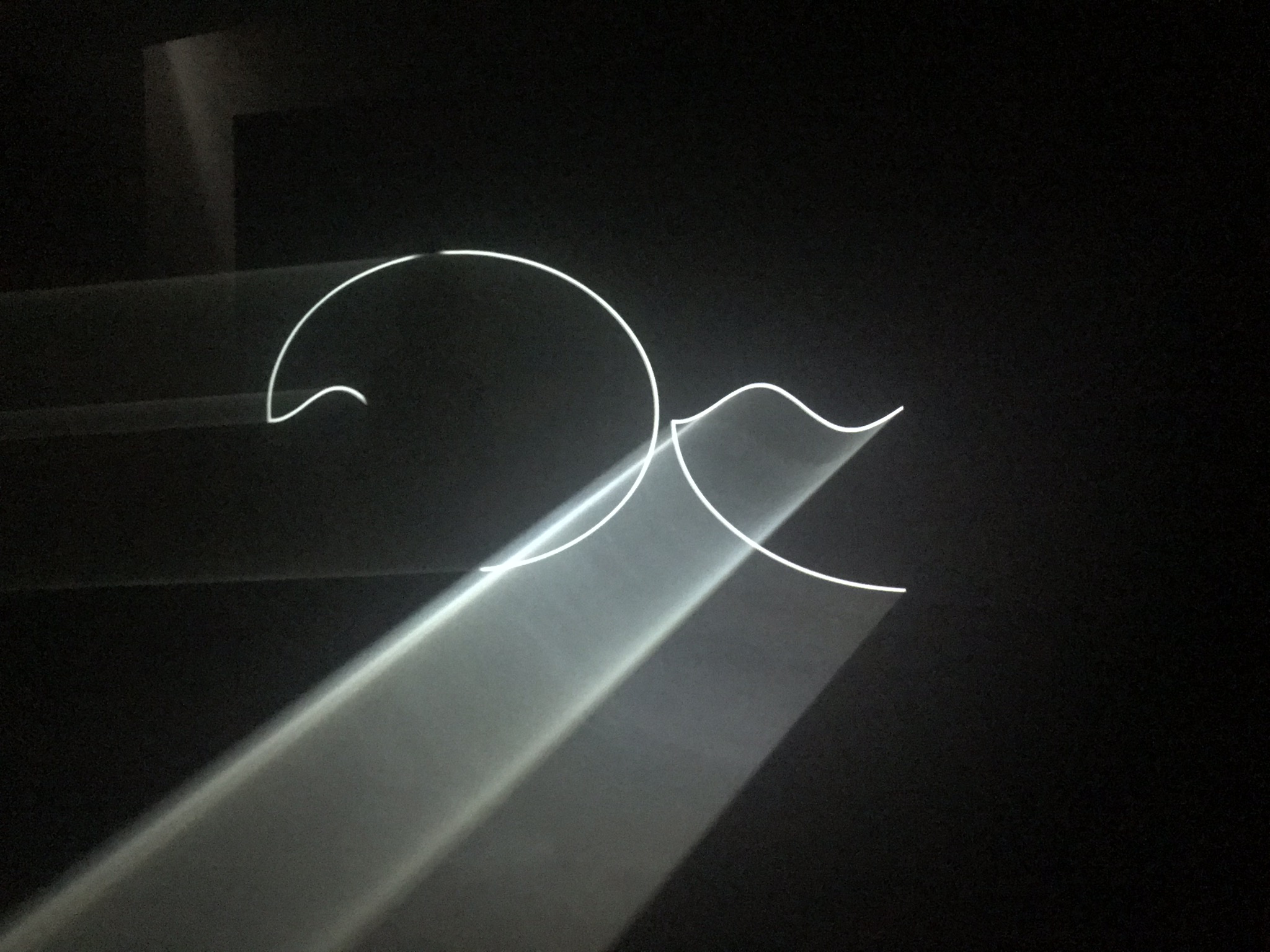

Once sketched, McCall creates a rotating film, which is then projected in smoke filled pitch-black environments, often with no sound, besides the tranquil buzz of the projector at work. The Hepworth offers a true insight into McCall’s oeuvre – his first video performances with Schleeman, his photographs, cone drawings and watercolours. He creates a map to indicate all of England’s lighthouses, from which we see him derive inspiration for his most famous pieces.

Leaving (With Two-Minute Silence) was the work we spent most time with. Two cones are projected side by side, the sound of waves crashing accompanying them as one grows and the other shrinks in response. As the loop continues, we are left in complete silence for two minutes. This ebb and flow, the measured passing of time with its pure cyclicality is hard to leave behind.

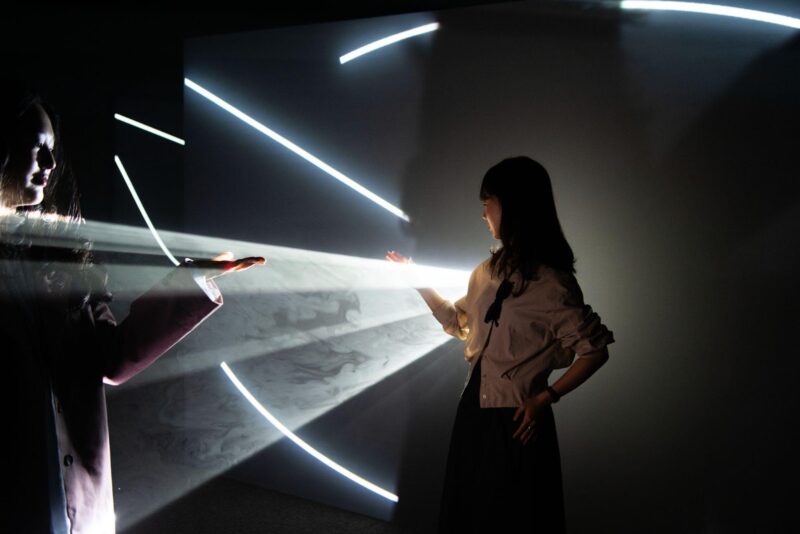

Anthony McCall, Face to Face

Face to Face on the other hand offered a more static landscape, as the two light sculptures faced each other, creating McCall’s geometric wonders on two opposing screens. It is truly hard to describe how powerful the sensation of touching McCall’s pieces is – moving fingers across it resembles plucking chords on an instrument whilst at the same time allowing the music it produces to pass through your body.

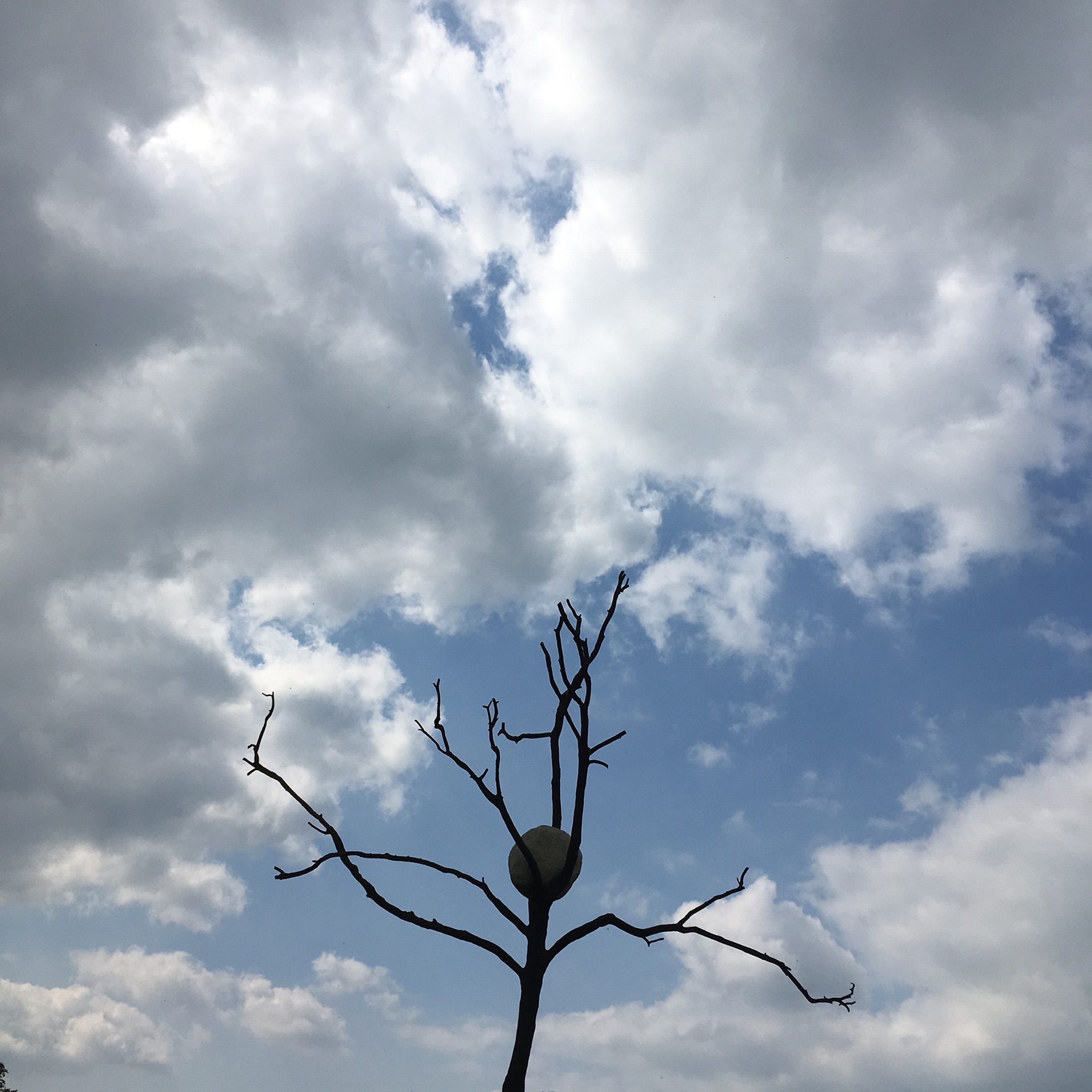

Giuseppe Penone, Luce e Ombra

Readjusting to the incredibly bright light took a while and we eventually left Chipperfield’s stunning building for what we envisioned to be a one hour walk to Yorkshire Sculpture Park (YSP). As it turns out, unless one is prepared to walk two hours and a half on a highway, the YSP is really only accessible by car. Determined to see Giuseppe Penone’s exhibition we set off and arrived at the idyllic site. In 2017 Burberry displayed Henry Moore’s sculptures to illustrate the inspiration behind Christopher Bailey’s collection. I distinctly remember noting Moore’s love for sheep and, in turn, was told that the animals love to graze near his sculptures. Witnessing this symbiotic relationship at YSP was incredible. The park itself deserves a separate section, so I will endeavour to focus on Penone’s A Tree in the Wood.

My interactions with Penone’s works are largely due to being from Rome, where his sculptures – imposing and intimidating trees with beautiful white stones, are found outside the Fendi headquarters. This is the sculptor’s largest UK show and the location could not have been more fitting.

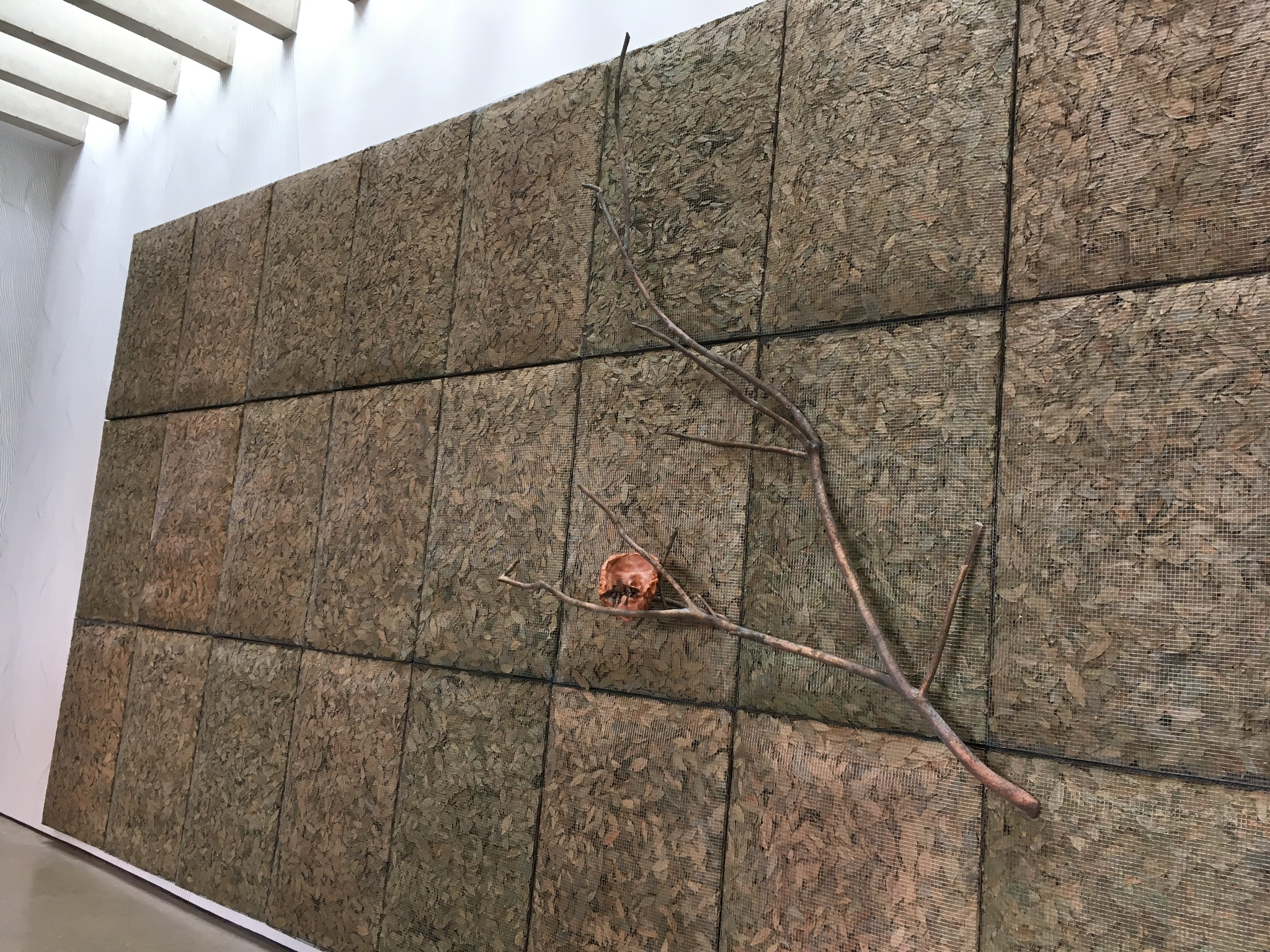

Giuseppe Penone, Respirare l’ombra

Penone’s works are characterised by wonderful natural elements being interrupted or somewhat diverted by an apparent outsider, another feature that on paper may feel at odds with the composition yet in practice brings out its harmony. We find this particularly with Respirare l’ombra, in which Penone sets an enormous blanket of laurel leaves behind a cage, as a mask perched on a branch seems to press its face against it. In emulating the mask itself we become aware of the intoxicatingly fresh scent of the laurel leaves whose pervasiveness is rendered more powerful because they are constrained. The cage suggests that they are in fact alive, ready to immerse the room washed with light we are currently in.

Matrice is perhaps the most awe inspiring of the works on display due to the balance between its sheer scale and fragility. A fir tree, cut in half runs through the entirety of the gallery, its branches resembling the legs of an insect, unable to move and at the mercy of visitors not to disturb it. Penone’s carvings are visible inside, running through, emulating a vein.

Throughout the show, the artist’s ability to be both a conduit for life and an embalmer becomes a constant. We see this dual nature emerge as he freezes twigs in slabs of marble or, as an alternative reading, allows lifeless marble to host shadows of the living. Again in Albero folgorato, where he creates a cast of a tree struck by lightning and then adorns its inside with gold leaf, allowing it to be caressed by sunlight again. Penone’s works have a spirit of their own, becoming woodland creatures who have temporarily chosen to inhabit these stunning acres of land.

Block Universe is on until 3 June across various London locations.

Anthony McCall: Solid Light Works is on at The Hepworth Wakefield until 3 June 2018.

Giuseppe Penone: A Tree in the Wood is on at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park until 28 April 2019.