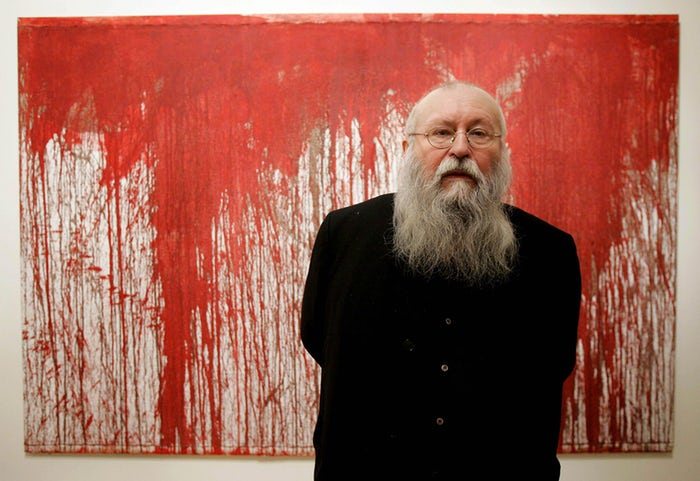

Austrian avant-garde artist Hermann Nitsch is in Australia for Mona’s annual midwinter arts festival, Dark Mofo. Photograph: Matt Dunham/Reuters

“I was never interested to make provocation,” says Austrian avant-garde artist Hermann Nitsch.

The 78-year-old artist is in Australia for Mona’s annual midwinter arts festival, Dark Mofo. Since Nitsch arrived in Hobart a week ago, the location of his performance, 150.Action, and the rehearsals for it have been a closely guarded secret.

The announcement that Nitsch would be conducting an art performance at Dark Mofo involving the carcass of a humanely slaughtered bull was controversial from the get-go. It sparked protests from animal rights groups, who petitioned and engaged in direct action against the work. The entire ticket allocation was voided in May when Mona learned that activists had been acquiring tickets with the intention of “denying access to others, or disrupting the performance an attempt to sabotage the work”. Mona’s patron, David Walsh, has also been receiving death threats.

Ticket reallocation was finalised only a couple of days ago. Audience members for the event have been given a meeting place and time, and told they will be escorted to a secret location, but no other details.

When we meet in Hobart, the day before the performance is to take place, the protests and controversy are all anyone can talk about; yet I am under strict instructions not to ask Nitsch about it.

Nitsch is old, short and very large-bellied. He is dressed in a black leather coat and black embroidered scarf, his wiry, greying beard sitting over his chin and reaching to his wide chest. His accent is heavy and his voice is gravelly.

It becomes clear early on in our interview that words are going to be a problem. Nitsch speaks English but not enough for the kinds of questions I want to ask: my first question is too conceptual and has to be translated for him to understand it properly. I want to talk about transgression; he wants to know how I understand it first.

“I want to show with my work everything that is,” he says. “…I don’t know what is bad or what is good.”

Nitsch’s art comes in the tradition of the Viennese Actionists, who came to prominence in the late 50s and early 60s, in the context of a physically and culturally ruined post-war Europe. Nitsch, though, is the most enduring of his peers. His performances – called “actions” – are striking for their use of animal carcasses, entrails and a large volume of blood as materials. The performances, which have taken place around the world since the 60s, call to mind pagan rituals, cult sacrifice, and crucifixion.

While his works often invoke horror in audiences, it is important to note that this is not the only feeling they invoke – only, perhaps, the most easily transmittable through film and photography. They also involve music, intense scents, eating and drinking; materials used include not just animal remains but tomatoes, lilies, sugar cubes.

All art, he says, “tears the borders apart”. That is what art has to do. But if we understand transgressive art as a conscious exposure of what social and cultural conventions require or insist should be hidden away, then Nitsch’s work takes that to its very literal, visceral core, turning the body itself inside out to see what would normally not be seen.

Yet this, in Nitsch’s mind, is merely showing what is already there: exposing what we know to exist but choose to turn away from. In this respect, the animal rights activists and the target of their ire may have some common ground: if industry has alienated us from the source of our subsistence – from the reality of the very food we eat – then it has also alienated us from our senses.

“I want only to show what is,” says Nitsch. “I never was interested to make provocation. I want to show intensity. And let’s say, maybe in intensity is a kind of provocation, but for me [it] always is important to show life and to celebrate life.”

The concept of intensity is key to understanding the actions themselves. The actions push performers and audiences towards the extremes of feeling – horror, ecstasy, joy – by embracing the extremes of experience: birth, orgasm, death. The very practice of the “action” – the performance, the heightened drama of it – was an attempt to move towards a truer, more immediate and all-encompassing art. The artworks produced during the events – not only the photographic records but bloodied canvases and the like, which are later exhibited – are called “relics”: a reminder of the intensity that once occurred, but no substitute for it.

“I want to make people more intensive. I try to show the people how it’s possible to live intensively,” Nitsch says.

Surrendering to the senses, giving yourself entirely over to feeling – that is Nitsch’s primary concern. In that respect, to him, my questions, and our interview, are in a way redundant; engaging on a conceptual or intellectual level, attempting to distil the project into theory – in essence, documentation or criticism itself – becomes futile. Words aren’t just a problem in a practical sense: their failure reinforces the conceit of the work itself.

Nitsch has, in the past, referred to his work as a “formidable fight – that between Dionysis and Christ”. He explains to me that he is interested in all religions, but “it’s also important if religion says yes to life or no to life. Buddhism, Hinduism, Christianity – they are all not so happy with life … I like life, I like being, and I like the principle of Dionysis, because that’s a very big yes to life.”

• Hermann Nitsch: 150.Action is occurring at Dark Mofo, Hobart, on Saturday 17 June. Hermann Nitsch will be appearing in conversation at Federation Concert Hall, Hobart, at 1pm Sunday 18 June

• Guardian Australia was a guest of Dark Mofo

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.