British artist Hannah Perry took over Manhattan during Frieze New York this year, with a solo show that opened on 3rd May at Arsenal Contemporary entitled Viruses Worth Spreading (on until 2nd July 2017). That same week, she did a killer performance in collaboration with composer and musician Adam Bainbridge, performance curator Shazam Khan and clothing designer HYDRA. Combining, video, sculpture, installation, music and performance, Perry makes artworks with an urban tongue that jolt, stir and jump-cut their way through a collision course with class, gender, sex, power and youth lifestyle. Employing lo-fi technologies, Perry layers and loops, samples and processes pieces of video footage, text and sound to create erratic, rhythmic artworks with non-linear narratives that give clues to the artist’s own lived experience. Hailing from Chester in the North West of England, Perry lives the life of a nomadic artist, having lived for brief periods in Los Angeles, Montreal, Istanbul, Las Vegas and London over the last few years; however, her work (in particular, the sculptures) pays homage to the working class aesthetic of northern England, using aluminium and crushed car parts from an auto body shop to reimagine a world of adolescent joyriding in pimped-out speedsters. For her New York solo show, Perry transformed the main gallery into a post-club crash pad with moody, purple lighting, a split monitor hanging from the ceiling playing a new 20-minute single channel video and various duvets and foam mattresses for viewer seating.

Congrats on your solo exhibition at Arsenal Contemporary in New York! Let’s start with the title – Viruses Worth Spreading. For me, it brings up promiscuity and feminine sexual desire, themes often considered taboo in our phallocentric society. Could you talk about the overriding themes in your new show and how you overlay “gender” onto your work?

Within our phallus obsessed society, I guess this is the equivalent of my dick shaped art. Promiscuous is a term that is almost always used when speaking about a woman and it is pejorative. Although promiscuity is no longer viewed quite as negatively as it used to be, I would say mental health is much more out of bounds.

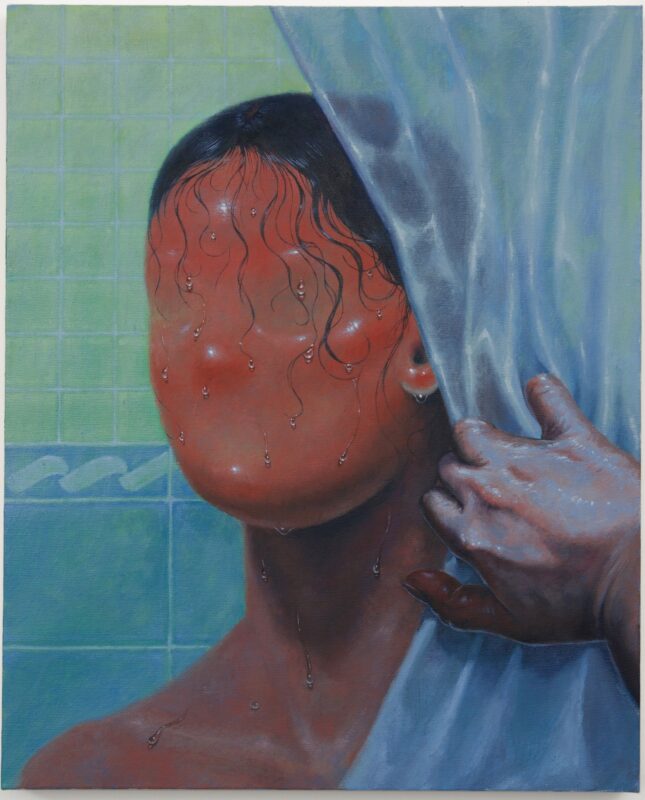

The themes swayed interchangeably between trauma, lust, heartache and anxiety. Imagined in a realm where relationships share equal footing in the virtual and real world—somewhere between online stalking, love letters, sexts and selfies.

The title came from a line of a script that I wrote, conjuring the clichéd image of ‘the hysterical woman’ who has lost control. The text was written whilst researching and combined a mixture of that research with memes, public posts online and personal emails that I will never send.

The whole undercurrent of the show was an attempt to inhabit and take control of negative stereotypes attached to genders, playing up to something whilst at the same time ridiculing it and then linking female sexuality to a technological virus – which is capable of copying itself and typically has a detrimental effect, such as corrupting the system or destroying data.

Please tell me about your multi-sensorial installation at Viruses Worth Spreading featuring your new video Cry Daggers. Is it important for you that the video sits within this darkened womb-like room? How do the various elements – warped walls, duvets covered in expanding foam and hair extensions, strapped-up foam mattresses, purple lighting, footage of LA car rides and GIF-like selfies, and a script describing tales of revenge and sexual desire – fit together?

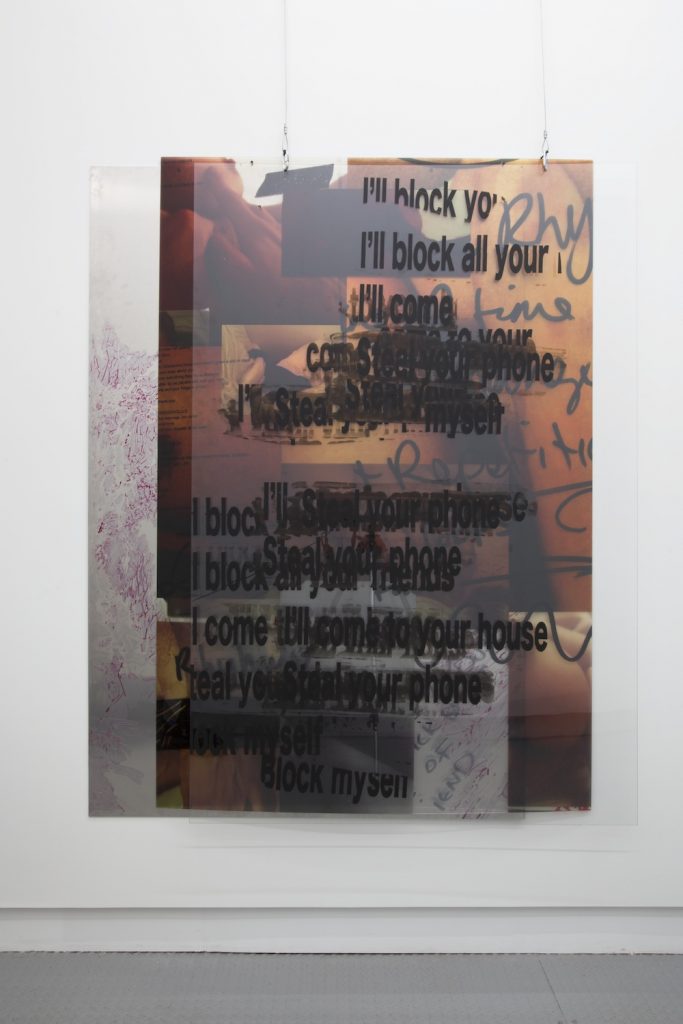

The script was written from producing a large collage of images, text print-outs and handwriting – all set out like a mind map spanning the length of a wall in my studio. It came to life in three parts. Firstly, in a collection of wall-based works that consisted of rephotographed, distilled close-ups from its original form (which I violently destroyed) on aluminium and plexi and combined with screen printing. Secondly, as a running commentary through the video ‘Cry Daggers’, and finally as the narration to a live performance set three days after the opening.

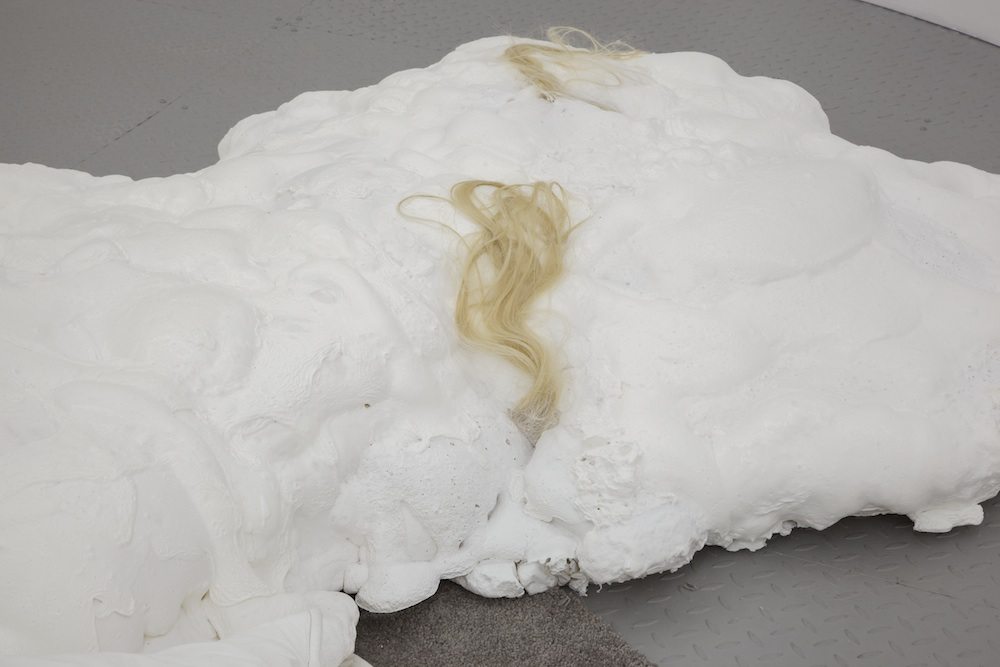

For the installation, I brought the walls inward to create a curvy, body-like, glowing space. The collection of beds and duvets were made out of marshmallowy like material which had blond hair extensions and distorted foam mattresses upholstered in PVC, bound up with industrial metal strapping. It was about creating an intimacy within the space to experience and watch the film, inviting people into bed like sculptures and duvets to get wrapped up in.

The image of the auto body reoccurs time and time again within my work, the relics of some power play or car crash sex scene. Ruptured body parts were bound between sheets of plexi and hung in windows on scaffolding pipes. The impact imaged as a site of brute force, conjuring the clichéd image of both trauma and, this time lathered in a drippy gooey latex liquid, episodes of retaliation and lust.

The possible relationships between femininity and hysteria, machismo and industrialism are left to drift somewhere in between contingency and essence, threaded through the intimate and the shared.

For this show, you also presented a performance during the opening week, working with several dancers, a choreographer, a composer and a clothing designer – all with an unmistakable youth culture/club vibe. How do you approach this process with its multitude of different human elements? How did this particular performance activate the installation space?

When I was writing the text I sat with four girls, and together we had a think tank discussion on the themes around the work. So when it came to bringing that to life, it made sense to approach the performance collaboratively. Richie Shazam curated a group of performers, and we all lay together in the installation and watched ‘Cry Daggers’. I then sent everyone in the group a recording of the script that they each went home and listened to. Each performer interpreted it in a different way, with a different intensity and hooked onto a specific element which resonated with them. There were moments where I choreographed sections or directed parts but at the core each performer had their own specific interpretation of the emotions and tone of the piece. This for me was the aspect that resonated the most.

I also sent the script recording to an incredibly talented musician producer called Adam Bainbridge who scored an amazing soundtrack for the piece, and lastly l I worked with Hydra SARTORIAL LATEX, a fashion designer who shares a similar sensibility to materials I was engaging with in my work.

You famously quipped about five years ago, “I didn’t step into an art gallery until I was 18. It’s reflected in my work. It is more about society than art history.” What parts of “society” do you portray in your work?

I suppose I am talking about being from labouring class sensibilities as I come from a family of metal fabricators or service industry work and I have a sense of pride in that.

When in NY, I watched the John Akomfrah art documentary at MOMA about Stuart Hall, the Jamaican-born cultural theorist and leader of the British New Left. It was incredible. I have been reading Stuart Halls’ essay – In low life and high theory – where he talks about the connection between the life which working class people made for themselves in industrial society and the body of socialist theory which came out of it: ‘the interpretation of theory and experience’ focus on the ‘spirit of collectiveness’ which is too often scooped up, aestheticised, appropriated and fetishised.

Having had the opportunity to work with many young people on projects, particularly in South East London, I realised that a lot of the misaligned youths that I was working with were artists of some kind, but were born into the wrong class, without certain resources. The mechanisms of social mobility, that existed when I was younger and enabled me to be situated in a privileged cultural space now, don’t exist anymore unfortunately.

In the same way I work with gender in my work, being working class means having an understanding of what it means to experience an unjust socio-economic system. The reality of both of these concerns is things like loan sharks praying on family members when they are broke and vulnerable or fighting for acknowledgement of your credibility and hard work when undermined with sexist comments. There is a difference between a genuine sense of community and a false identification with a group

So not going to an art gallery until i was 18 was referring to social class and accessibility.

Congrats again on being part of the first group of artists to be in residence for the next two years in the neoclassical Somerset House overlooking the Thames in Central London! How will you use this new workspace? What are your plans for this residency?

Well, at the moment, I am doing a bunch of inductions in the Somerset House workshops. It’s an incredibly beautiful setting to be in and feels very Dickensian to be there every day. It’s a two-year studio residency but also feels like being back at art school: firstly, because of the sense of community amongst all of the artists and secondly, because of the amazing resources. When you finish art school, you look back and think of all the things you didn’t quite get round to learning, such as new processes and new materials, so it’s a chance to go back to that in a way. I am very lucky.

One last question… As a female artist whose work makes public your own private relationships and experiences, how do you navigate this space where issues of voyeurism and power relationships come to the fore?

A lot of my work is mediated and fragmented through the process. Reprocessing, degrading, altering and defusing the images, video and sounds.

Conceptually, in the NY show, there are a lot of expressions of anger, trauma and grief through the posture of a relationship breaking down last year and the emotions that spiralled out of that – such as anger, a sense of loss, hopelessness, injustice and grief. Looking back now, it was all a cloak or mask to coincide with the loss of my best friend and long term collaborator, Pete Morrow, who sadly took this life in January of last year. I worked with Pete on various performances, like at Boiler Room and V22 and countless other video and music projects. It was easier to reconcile with a breakup than it was to process death. So there are many layers of public and many layers of private. Working with personal content can be a vulnerable position but the vulnerability is the strength.

Voyeurism and power plays are unfortunately something that women have to grapple with within every area. Being unapologetic about those experiences is exactly what that show was all about.

Links

Hannah Perry: Viruses Worth Spreading, Arsenal Contemporary, New York (3 May – 2 July 2017): http://www.arsenalmontreal.com/en/exhibitions/?t=now&w=new_york

Artist’s website: http://www.hannahperry.com

Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin website: http://www.cfa-berlin.de/artists/hannah_perry

Captions

All images courtesy of the artist and Arsenal Contemporary, New York.

Image 1: Hannah Perry, installation view of Cry Daggers (HD video, 2017) in Viruses Worth Spreading, Arsenal Contemporary, New York, 2017.

Image 2: Hannah Perry, Your Ass is Grass (And I’m Gonna Mow It) (2017), silkscreen on aluminium, digital perplex print on plexiglass, silkscreen on plexiglass, 152.4 x 182.88 cm.

Image 3: Hannah Perry, Cock Blocking (2017), foam, vinyl, steel strapping, 134.6 x 76.2 x 73.6 cm.

Image 4: Hannah Perry, Cucci Copey (detail) (2017), expanding foam, synthetic hair extensions, duvet vinyl, 139.7 x 205.7 x 35.5 cm.

Image 5: Hannah Perry, installation view of Pretty and Trauma Junky (both 2017, plexiglass, crushed car parts, foam, latex) in Viruses Worth Spreading, Arsenal Contemporary, New York, 2017.

Image 6: Hannah Perry, exhibition view of Viruses Worth Spreading, Arsenal Contemporary, New York, 2017.

Image 7: Hannah Perry, exhibition view of Viruses Worth Spreading, Arsenal Contemporary, New York, 2017.

About the Artist

Born in Chester in 1984, Hannah Perry lives and works in London. She graduated from Goldsmiths College in 2009 and from the Royal Academy Schools in 2014. Her solo shows include Viruses Worth Spreading, Arsenal Contemporary, New York (2017); 100 Problems, Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin (2016); Mercury Retrograde, Seventeen, London (2015); You’re gonna be great, Jeanine Hofland, Amsterdam (2015); Always, Steve Turner, Los Angeles (2015); and Hannah Perry, Zabludowicz Collection, London (2012). Recent institutional group-exhibitions include: If we think bad, Arsenal Montreal (2016); Private Settings: Art After the Internet, MOMA Warsaw; New Order II, Saatchi Gallery, London (2014); A sense of things, Zabludowicz Collection, London (2014); Alternative Space from London: Arcadia Missa Off-Site, Astrup Fearnley Museet, Oslo (2014); Stedelijk at Trouw: Contemporary Art Club – DATA, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (2013); OPEN HEART SURGERY, Moving Museum, London (2013); and Dropbox, Modern Art Oxford, Oxford (2013). Performances by the artist have been hosted at Boiler Room, London (2015); Serpentine Gallery, London (2014); David Roberts Art Foundation, London (2014); Barbican Gallery, London (2013); V22, London (2012) and Zabludowicz Collection, London (2012).