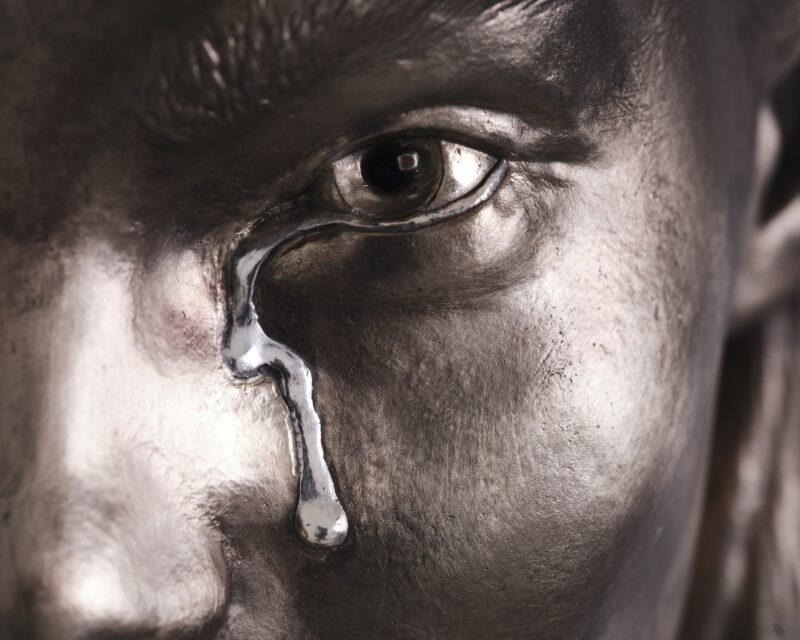

Troubled reception … graffiti in Athens referring to a horseback event that opened Documenta. Photograph: Louisa Gouliamaki/AFP/Getty

‘Hello, hello,” croaks a voice in the undergrowth. “This is Ben!” I’m in the lower gardens of the Byzantine and Christian Museum in Athens, where the sound of frogs and froglike voices seems to be coming from the flowers, bushes and trees that line its manmade waterway. It is a bizarre experience in what is otherwise an oasis of calm. But this amphibian chorus is actually a work of contemporary art, a piece of “sonic graffiti” emanating from 24 speakers concealed in the greenery. Why is this august museum – famed for its religious art, its ancient manuscripts, icons and ceramics – venturing into such strange new territory? Because Documenta has come to town.

Documenta is the year’s most anticipated art event and, for the first time, the disorientating extravaganza has spread itself across a guest city as well as Kassel, the German town where it was born 10 years after the second world war. “We wanted to be open to contemporary art,” says Katerina Dellaporta, the Athens museum’s director. “But how much the average Greek is open to it is another question.”

Dellaporta’s world has changed in ways both big and small. Those who might never have ventured into the venue – diverse groups of Britons, Germans and natives – are now among its most faithful visitors. At odd hours, they can be glimpsed working their way around the gardens, ears cocked. Described as “a reverie”, the work was conceived for the mega art show by the late US artist Ben Patterson. It is a nod not only to Aristophanes’s comedy The Frogs, but to the ancient Ilissos river that the museum’s gardens reputedly straddle. Patterson has joyfully played on the fact that, in the 5th century BC, the area was known as Frog Island.

This is the 14th Documenta. Its original mission, in a town that had felt the full force of Allied air raids, was to bring modern western art to audiences denied its pleasures by the Third Reich’s ban on works it regarded as degenerate. Such was its success that it became a five-yearly institution.

From the outset, the dual location has been controversial. No other edition has faced such expectation of failure or success. The double act was announced at the height of rancour between Germany and Greece, the EU’s strongest and weakest members. Anxiety abounded. As the art fair’s birthplace and traditional home, Kassel feared the loss of visitors to Athens, while the latter fretted about hosting an event that was as big and potentially burdensome as the 2004 Olympics – for many the single largest cause of Greece’s near-bankrupt state.

The wisdom of transplanting an organ of such scale and scope to what the German media mockingly called a Schuldenland, or debtor country, was also questioned. How could Greece – the antithesis of German fiscal rectitude, the embodiment of failure in Europe – possibly rise to the challenge of offering itself as a place for major discussion on global contemporary art?

For Adam Szymcyk, Documenta 14’s artistic director, navigating such chasms has not been easy. The Polish curator has described the event as the equivalent of the international art world’s conscience, “with each edition mirroring, witnessing and fiercely commenting on its time”. As the meeting point of the economic and migrant crises that have consumed Europe, Athens offered “fertile land” to explore the global complexities of possession and dispossession, displacement and debt.

Despite a budget of €37m – at least half of which has been directed to hosting the event in the austerity-ravaged Greek capital – it has also offered plenty of ground for disagreement and heated debate. Documenta 14’s launch in Athens last month (the second part opens in Kassel on 10 June) came amid accusations of “colonial attitudes” with some employees complaining of exploitation and being deliberately misled over invigilator fees. Even the exhibition’s working title, Learning from Athens, was called condescending.

Graffiti castigating the spectacle as “Crapumenta 14” soon appeared. “I refuse to exoticize myself to increase your cultural capital. Signed: The People,” has been a particular favourite. While Giorgos Kaminis, the city’s mayor, maintained Documenta was fantastic for tourism (as Aegean Airlines’ new and fully booked Kassel to Athens route has proved), critics complained that it amounted to the worst kind of crisis tourism.

“There’s anger because they haven’t taken circumstance into account,” says Nadja Argyropoulou, a curator in Athens. “Their theory is beautiful, radical and timely, but they didn’t mingle or take the leap into the everyday or address the reality here. Circumstance is what humbles theory and makes art as important as real life.”

For detractors, Szymczyk had become the embodiment of the corporate, neo-liberal order he professes to abhor, a purveyor of the worst kind of soft German power. Not only was the exhibition abstruse, it had committed the cardinal sin of omitting Greek artists and curators. “There are so many names,” Argyropoulou says. “People who should have been in it but were never approached. But please also write that we want them to succeed. If they fail, it is us who will be left with their ruins of contemporary art – and in a country that is continually looking to its past, with unresolved questions of identity, that would be disastrous.”

At 46, Szymczyk has a reputation as a maverick. His desire to surprise, pushing the boundaries of art, has won him praise. Choosing to split the show is his riskiest move yet. Almost all of the 160 participating artists are unknowns, although curators contend they pull off the not inconsiderable feat of talking truth to power. Until a week before the opening, most of the exhibition’s 40 venues – facilities offered by the Greek state – had still not been pinned down.

But for all the tumult, which has clearly shaken his team, Szymczyk remains convinced that doubling Documenta’s perspective was the right thing to do. “Athens is one of the most interesting cities in Europe,” he says, sipping coffee in a 1930s building that serves as one of Documenta’s offices. “It is one of the very few places currently reinventing itself. The city is fertile ground for people and ideas. It has been pretty much wasted in the last 10 years.”

At a time of populism and confused political agendas, Athens seemed the perfect counterpoint to distinctly provincial Kassel. “I didn’t think Kassel was the best place to think about global ideas and politics. I felt it needed another place to keep it in check.”

Up close Szymczyk has the air of a young David Bowie; his hair flopping in layers around his face, his eyes a combination of mischief and mystery. Tall and exceptionally thin, he is wearing a Guatemalan sash just above his waist when we meet, and a pair of noticeably scuffed fake crocodile skin boots. The artists are finding Athens “extremely enjoyable” though challenging as well. He himself is transfixed with the idea of western civilisation being embedded in a monument on a rock. And the numbers are good: in a matter of weeks, over 100,000 have seen the show, although most aren’t Greeks but foreigners who have flown in.

While the newly opened Museum of Contemporary Art – housed in a former brewery and known as EMST – is the main venue and will send a selection of its own collection to Kassel, Documenta has been deliberately scattered across Athens, which is a chaotic place at the best of times.

Visitors were recently directed to “a specially prepared orchard pasture” at the city’s Agricultural University to view 54 lambs, each representing a country on the African continent, and dyed by the Malian artist Aboubakar Fofana differing shades of indigo to highlight the perils of migration. In fact, migration is a central theme, with the Berlin-based Kurdish artist Hiwa K, who fled Iraq in 1996, presenting some of the best work. A video retraces his steps to freedom via Greece, while his one-room apartment currently graces the courtyard of the Benaki Museum.

Meanwhile, the Anishinaabe-Canadian artist Rebecca Belmore has carved a marble tent – the refuge of refugees world wide and symbol of the migrant crisis in Greece. It has been pitched, to the consternation of classical purists, within perfect view of the Periclean masterpiece that is the Acropolis.

Helena Papadopoulou, who runs Radio Athènes, an institute for the advancement of contemporary visual art, is among those who believe the split was inspired. “Greece has always focused on its ancient heritage at the expense of contemporary art,” she says. “What Documenta has done is emancipate the scene and energise people, and create a curiosity for Athens as a place where contemporary art can also be enjoyed. It has been hugely positive.”

The sad reality is that most Greeks won’t see Documenta 14, unable to identify with an exhibition that often feels lost in its own jargon. The German juggernaut will pass through – transforming venues like the Byzantine and Christian art museum – and then be largely forgotten. But for those who do attend, the otherworldly, almost dreamlike quality of the Athens leg may ultimately be its legacy, one that seeps into the conscience long after the viewing.

“You feel Europe’s problems here,” says Els Van den Berg, a Dutch cultural policy-maker who flew in for the show. “You feel the poverty, you feel this atmosphere of loss,” she adds, as she excitedly makes her way from one venue on a potholed boulevard to another. “This is a Documenta that is deliberately disorientating. The experience as a whole, the curatorial story, is stronger than the works of art. That’s what makes it all so positive. ”

- Documenta 14 is in Athens until 16 July, and in Kassel from 10 June to 17 September.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.