Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable – Damien Hirst’s decade-in-the-making Venetian extravaganza – is as unbelievable as his title implies. I have never seen a bigger show in my life. The artist has filled not one but two museums with hundreds of objects in marble, gold and bronze, crystal, jade and malachite – heroes, gods and leviathans all supposedly lost in a legendary shipwreck 2,000 years ago and now raised from the Indian Ocean at Hirst’s personal expense. It is by turns marvellous and beautiful, prodigious, comic and monstrous.

The question of belief is in the air even before you enter the Punta della Dogana. Outside the former customs house is a lifesize statue of a man on a rearing horse, both constricted by a monumental snake. The man’s face is a terrified rictus, the horse strenuously anatomical in its every standing vein – this is the classical Laocoön statue crossed with the sculptures of Leonardo and Messerschmidt. It is both jaw-dropping and hyperbolic, with overtones of computer-generated movies. People touch it to see if the twinkling white substance is real, which it is: Carrara marble, in fact. And yet it looks fake.

Inside, in perfect Discovery Channel pastiche, the tale is told of a freed slave named Cif Amotan II (solve that anagram), who accumulated an immense fortune which he spent on the sunken treasures divers are now dredging up on the screen before you. This is quite obviously hokum. One glimpse of the synthetic blue coral, or the Versace bling of the golden head gingerly dislodged from the sea floor, should give the game away, even before you see the amazing “hoard”. But then again, these are in a true sense buried treasures: buried and then rediscovered for the sake of this footage. The joke is already more subtle than many of the objects; this is art for a post-truth world.

Here is a sword-wielding woman mounted on a gigantic bronze bear, and a cartwheel-sized calendar stone made by the Aztecs (an anachronism which has baffled historians, according to the museum-toned captions). Here are hieratic stone warriors and rusting scimitars, brine-damaged sphinxes and a magnificent carving of three-headed Cerberus. Golden discs and silver tablets glow in spotlit vitrines, their inscriptions – and even the language in which they are written – mysterious.

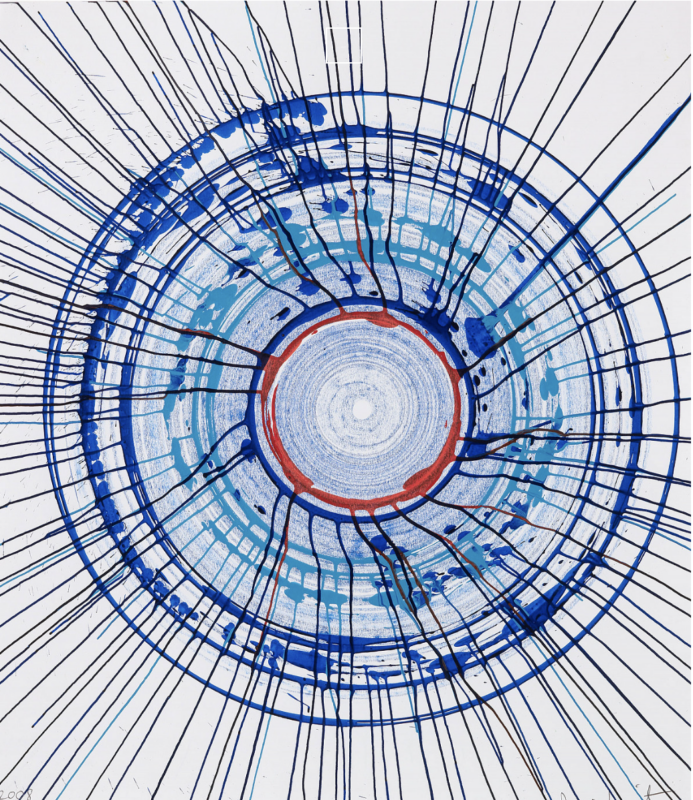

Hirst has imagined the fabled shield of Achilles, lost for millennia, and invented a whole sequence of ancient currencies. There are strange new abstract forms, their meaning unknown yet somehow latent in these enticing coinages. One wunderkammer contains enigmatic bronze oblongs conflating hints of oxen and Celtic crosses; another holds the tragically hunched figure of a beast of burden, as if Hirst was defying his more conservative critics by becoming an old-fashioned sculptor.

Sometimes the object may be familiar – a pharaonic bust, say, only marginally adapted – and sometimes utterly implausible, like the horned skull of a unicorn. Each is exquisitely made, and intended to inspire the awe and wonder (and shock) of ancient civilisations. There is a strong sense of Hirst’s exhilaration as a child in the British Museum; and possibly as a father too. Look closely and you see that one long-lost sword is stamped “SeaWorld” and several small figures, overgrown with coral, turn out to be toy Transformers.

It gradually becomes apparent that this is not just a spectacular combination of storytelling, visual invention and slow-building humour, but a meditation on belief and truth. Some visitors were clearly persuaded by all this fake antiquity, the day I was there, and then enjoyed the revelation of having been gulled. And this despite innumerable clues: the pharaoh looks suspiciously like Pharrell Williams; the Medusa’s head is a 3D reprise of Caravaggio’s masterpiece; “Made in China” is imprinted, albeit on the back, of one statue.

This art about what we think art might be is based on a lifetime’s looking. Dürer’s celebrated Praying Hands, here carved in jade, become a Chinese worshipful greeting. His rhinoceros, conflated with hints of Shakespeare and the Elephant Man, aptly makes the figure of Proteus. There is something of Daumier’s donkey, from the Don Quixote paintings, about that poor beast of burden. Time is circular. All cultures generate others; art doesn’t just arrive straight out of the desert.

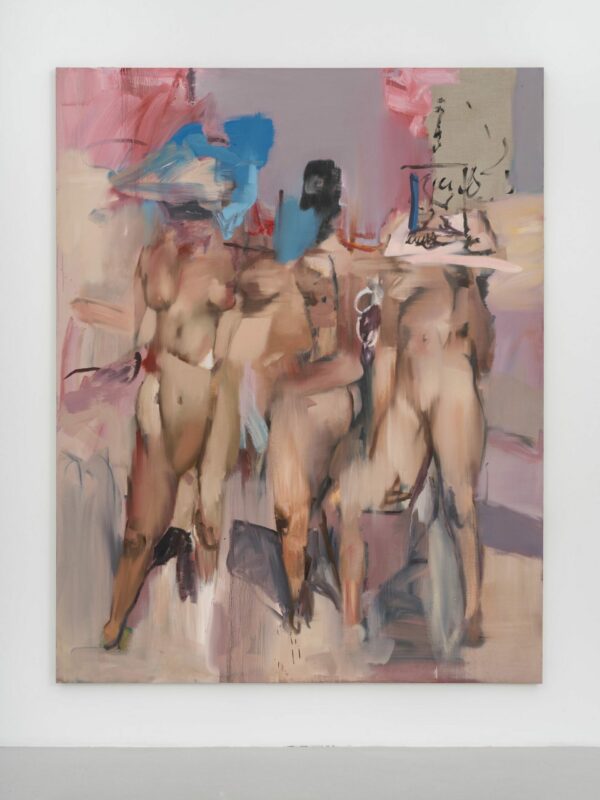

Hirst can’t resist a sight gag, of course. Four vast fertility goddesses – limbless bronze torsos – appear mounted on pedestals, and then again photoshopped into a period photo of Britain’s first surrealist show. But those weird proportions in fact belong to Barbie. The joke turns serious. Every time you’re invited to regard some artefact as far-fetched, outlandish, you are urged to consider something equally improbable from real life. Our belief in mermaids, for instance, which endured despite the discovery of the narwhal with its spiralling horn. The legend of Cyclops, confirmed for some by the discovery of a mammoth’s skull with its apparently unique eye socket. There’s a cast of a skull in this show… or so runs the claim.

And how would we believe in cat gods, dog demons or multi-limbed deities without the aid of art? And in what would the rich invest their money and faith? One subplot of this show homes in on collectors, from Cif Amotan to today’s zillionaires to the artist himself, also an acquisitive creature. If Hirst is forever associated with money – from the diamond-encrusted skull to the sell-out Sotheby’s show of 2008 – here he parodies the whole tradition of art as shopping.

In the 18th-century customs house, the original objects appear barnacled and eroded as if raised straight from the shining waters outside. Up the Grand Canal, in the second half of the show at the Palazzo Grassi, they reappear – damage repaired, missing limbs recreated – as the priceless possessions of the wealthy collectors who once lived in that palace. And then again, scaled down in rock crystal or gold, as baubles for the rococo salon.

This has been Hirst’s own business model for decades – recycling his works in different sizes, media and prices. And while he may be mocking his blue-chip clients here with some truly nauseating reprises in crystal and steel, he is sending himself up as well. Worst of the shockers at the Palazzo Grassi is a horrendous lifesize tableau – carved from pure lapis lazuli – of Andromeda chained to her rock and menaced not just by the sea monster but by a gigantic shark rearing out of the water – a play on Spielberg and on Hirst too, of course, with curly waves out of Hokusai.

The value of art, its meaning and worth: how are these to be determined – by the market, or with our eyes? These vital questions are summoned by the contrast between the two venues, between the exceptional creations at the customs house and their expensive knock-offs at the palace. In the former, Hirst has sculpted a brilliant incarnation of William Blake’s The Ghost of a Flea as a small, complex head, with an entirely alien force of personality; at the palace, the ghost becomes a gross striding machine, 60ft high (a size gag) and covered in coral like extruded toothpaste. But in the same museum, tellingly, Hirst portrays himself as The Collector – double-chinned, barrel-chested and cankered with coral: somewhere between a bloated bronze Caesar and a sad-eyed Messerschmidt bust.

The Treasures of the Wreck of the Unbelievable amounts to an imaginary past and a prediction of its own future. When the show ends, every work will be up for sale if it isn’t already. Collectors who can’t house a muckle monster can still buy a drawing signed “In this Dream” (another personal anagram). But it is impossible to believe any more that this is what really counts for Damien Hirst. The true artwork was in the whole astonishing vision, the spectacle of a lifetime – his wondrous invented museum.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.