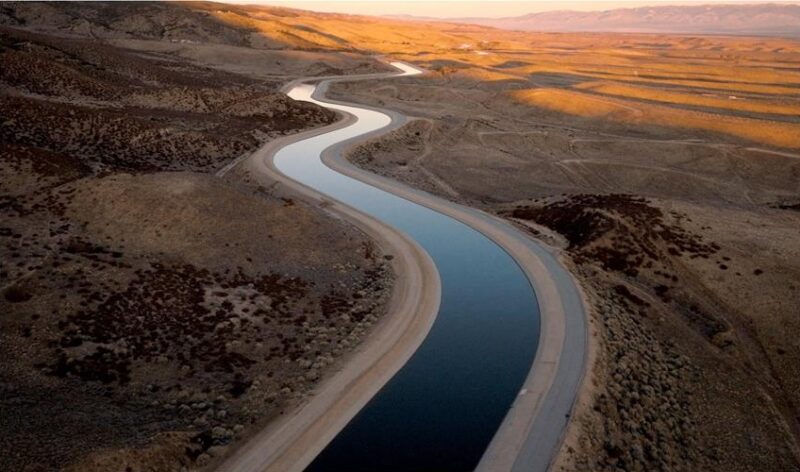

A shining house upon a hill … Mirage by Doug Aitken. Photograph: Desert X installation view of Doug Aitken’s Mirage, 2017, photo by Lance Gerber, courtesy the artist and Desert X

Speeding down the Gene Autry Trail, a Palm Springs desert road named after the singing cowboy, there are mountains to the north and south, and billboards on each side. Somewhere between the ads for milkshakes and legal counsel, there are large-scale images of mountains, and from three exacting positions on the road, they suddenly snap into place; for a few brief moments, they perfectly align with the jagged scenery. And just as quickly, they’re behind you. Perhaps you had imagined it, or perhaps you didn’t notice them at all.

This fleeting mirage is LA-based artist Jennifer Bolande’s new work, Visible Distance/Second Sight, a site-specific homage to the landscape. She and 15 other artists have come to Palm Springs and the surrounding area as part of Desert X, a new exhibition of large-scale installations that stretches across 45 miles until 30 April. (Not coincidentally, they’re sited along the path leading from Los Angeles to behemoth music festival Coachella, which also takes place in April).

“I live in New York, so I was interested in this sort of manifest destiny of the migration west,” English-born artistic director Neville Wakefield explains, citing a 19th-century idea that divine sanction validated the United States’ merciless, violent westward expansion, regardless of who was already living there.

“Yeah, no, it was awful,” Wakefield concedes. “But in terms of New York having evolved or devolved into a marketplace, I was a little bit disillusioned at having watched wealth evacuate art from the city center. It was interesting to do a show that recognized what’s happening on this coast.”

He invited the artists to search for their own sites in the desert, offering little in the way of curatorial direction in order to “allow the place itself to become the curator”. In the rich tradition of 1970s land art, it would be the myriad conditions unique to the desert – the pristine daylight, the untouched expanses of land, the brutal climate – that shaped the work.

After a bit of research, trial and error, Bahamian artist Tavares Strachan found himself an unused, 100,000 sq ft plot of land to use down a little dirt road in Rancho Mirage, a desert town where the population hovers around 18,000. He has carved an alternative landscape into the sand: 4ft deep craters and trenches in vaguely celestial shapes, lined with bars of cool yellow neon. From above, the lights spell out the simple proclamation, I Am, amid exploding shards of light, although you’d only see that online via images captured by drones. Standing inside this work during an inky black desert night is like standing on a glowing planet.

With a set of wheels and a decent 4G connection, anyone can come visit these sites, which have been conveniently plotted as Dropped Pins on Google Maps courtesy of the Desert X website. The best work engages the viewer with a dialogue with the land, including Sherin Guirguis’s One I Call, a clay bird refuge with glittery bits of gold in the open roof, nestled in the shadow of a steep cliff in the serene Whitewater Preserve. There’s also Lita Albuqerque’s hEARTH, a cobalt sculpture of a woman lying inside a circle of white sand, ear pressed to the earth as a low, looped reverberating chorus rhythmically repeats the question, “Why did you come here?”, which turns out to be an excellent question in the context of this show.

Richard Prince’s Third Place is literally garbage – an isolated cluster of small decaying buildings cluttered with beer cans, bags of dirty diapers, his work either plastered to the walls or weighed to the ground with rocks. He’s screenshotted and printed various naked women as “Family Tweets”, with typical Prince-repulsive captions to ponder: “One more of Dana. Mothers [sic] sister’s daughter. Smoking tits. No joke!”

The rest amount to punchlines and nice roadside diversions, places to stop for a quick selfie on par with the giant dinosaurs next to the gas station on Interstate 10. Both Glenn Kaino and Will Boone riff on legends of underground bunkers and tunnels with different holes in the ground (locked, accessible with a code you pick up at the hip Ace Hotel and Swim Club in Palm Springs). Rob Pruitt – the man who painted Barack Obama for every day of his presidency – has also inexplicably slipped another iteration of his recurring flea market inside the Palm Springs Museum.

But, making maximal use of the desert is Doug Aitken’s Mirage, a full-size single-family house that embodies typical Americana, save the fact that it’s completely clad in mirrors. Perched on the prime real estate of Chino Canyon’s unspoiled hillside, its surfaces become a collage of the surrounding environment: pristine reflections of sepia earth and bushes of marigolds, crystal-clear blues that disappear into the sky. At dusk, the house melts into gradients of purples and oranges, and inside, the picture windows frame the wind farms and city lights below. The mirrored walls and ceiling create an immersive, kaleidoscopic image of suburban sprawl, a marker of where civilization begins and ends.

Aitken describes the Desert X experiment as “a vast sprawling parkour” and “puzzle of pieces that are all different within the land”. “I wanted to be here to see where suburbia ends and the landscape begins. This location was kind of perfect in a way. You have the seductive beauty, and then you have the wind farm, and suburbia.”

Indeed, Desert X is a scavenger hunt for the ever-elusive unique experience, a rare thing in the Instagram age. Largely taking place on controlled private properties, however, it doesn’t quite capture the wild west it’s billing. In Aitken’s case, in the ongoing spirit of manifest destiny, the land surrounding his work is on its way to becoming Desert Palisades, a high-end residential community; the adjacent lot has already been sold, and in the distance, up the hill, a model home is decorated with expensive modernist furniture. The desert mythologies of self-actualization and adventure, according to Strachan, “are all part of the romance”.

The wildest piece in the show would be the one you’ll never see, Norma Jeane’s brilliant Shybot. It’s a solar-powered roving little vehicle that’s currently on an aimless mission through the desert, periodically sending information on its whereabouts to the cloud. Like the artists who inhabit the lands outside the safety of Desert X’s radius, it’s really come here to be alone; when its heat sensors pick up the presence of a human, it knows to speed off in the opposite direction.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.