FAD sat down with artist, Patrick Goddard to discuss his work and recent exhibition at Almanac Projects, Looking for The Ocean Estate.

Goddard is a London-based artist, currently studying for his DPhil at Ruskin College, Oxford, working in mediums such as video, installation and sculpture.

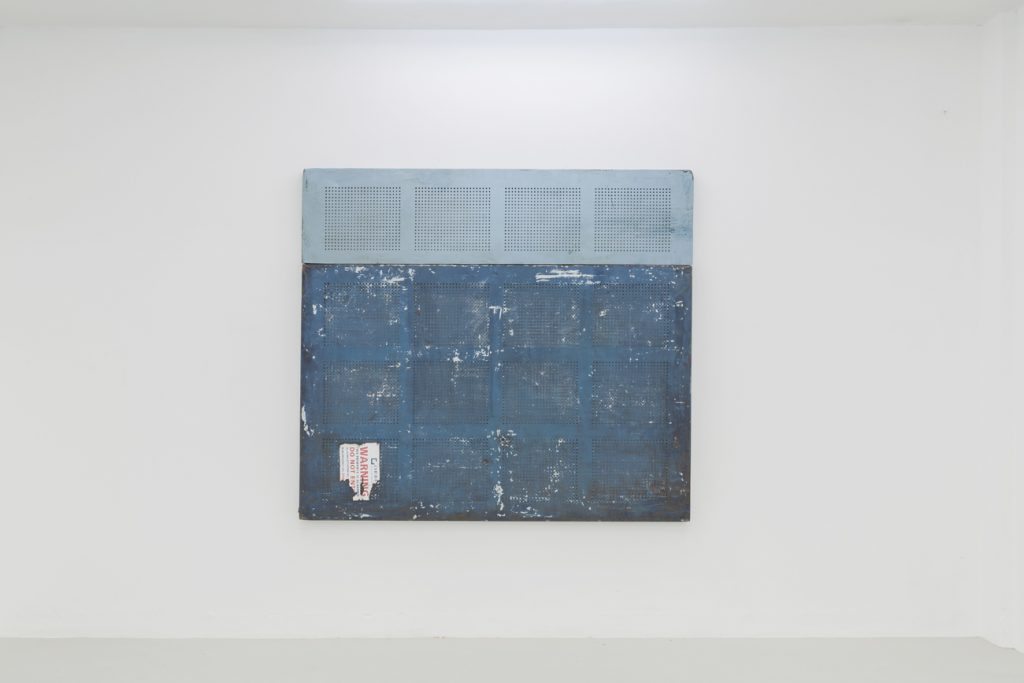

Patrick Goddard, “The Mediterranean (view to the north)”, 2016, Orbis security shutters, 178 x 200 x 7cm. Courtesy of the artist and Almanac, London/Turin. Photo: Oskar Proctor

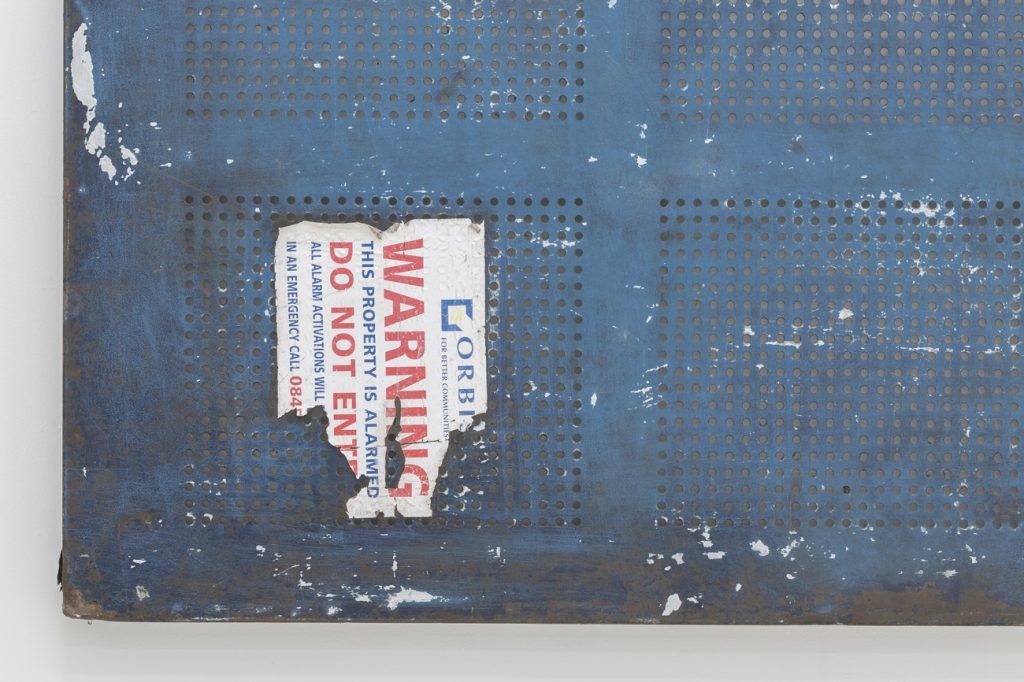

Patrick Goddard, “The Mediterranean (view to the north)”, 2016. (Detail). Courtesy of the artist and Almanac, London/Turin. Photo: Oskar Proctor

When you first enter your recent show at Almanac Projects, you are greeted by (unusually for your work) paintings or what you call ‘sculptures of paintings’. Can you talk a bit about how this came about?

I actually used to be a sculptor. For most of my BA and Masters, I did sculpture so they’re not super unusual. The series started in 2010 and I decided to revisit it in 2016. They’re all security shutters used to board up the windows of derelict, abandoned or unused – primarily council – properties in and around Hackney and Tower Hamlets. At the time, I was squatting, and the first three came off the windows of the property that I was living in. Each of my ‘sculpture paintings’ are the composite of two pieces of the same width but different heights put together to make a kind of horizon line. The whole series is called ‘Seascapes’ and they are essentially symbols of urban degradation/impending gentrification which have been taken out of context and repurposed as bourgeois art objects or specifically, commodity oriented art objects i.e. art fair friendly. I view them as sarcastic gestures towards a certain ilk of disingenuous pseudo-political artworks that fetishise urban decay. It’s also a bit of a dig at the history of painting and some of the highfalutin modernist ideals which now circulate on the auction market as ways for the super rich to diversify their investment portfolios, used to hide capital or dodge taxes and to launder dirty money.

Patrick Goddard, “Looking for The Ocean Estate”, 2016, SD digital file on LED video wall, 33’52” looping film. Courtesy of the artist and Almanac, London/Turin. Photo: Oskar Proctor

The second room shows your recent film, Looking for The Ocean Estate. Is the Ocean Estate real or fictional?

It’s real – although you’re right to ask it because the film is fictional or semi-fictional and by the end of making it, it became a universal, fictionalised story. It’s a real place. It’s not necessarily an examination into that place or if it is, it’s a failed examination. The film is pointedly called Looking for T he Ocean Estate. It’s never quite claiming to find it but it is a real place in Stepney Green. It used to be a big housing estate but the vast majority is now private and has been demolished with new flats built up.

Patrick Goddard, “Looking for The Ocean Estate”, 2016, SD digital file on LED video wall, 33’52” looping film. Courtesy of the artist and Almanac, London/Turin. Photo: Oskar Proctor

In terms of this relationship between fact and fiction, where do you see the viewer fitting in? When you watch the film, you’re aware it’s a mockumentary but you still become involved in the idea of the story.

Most people seem unsure as to the length or depth of the fictionality. I leave it deliberately ambiguous, for example, mostly calling the actors their own names. It’s not a stable relationship because each audience member will take a slightly different position towards the film and how they rate its fictionality. For some people it’s very important it’s not real, some think it’s totally real, for some people it doesn’t matter. I’m reluctant as the author to solidify one grade of importance I give to it. The original film started off being real with real interviews. Then i thought I’d intertwine it with some fake interviews but eventually, it all became fictional. But it’s based on real interviews and real conversations I had in my research and from memory when I lived on the estate.

Can you talk a bit about your decision to use a camcorder when filming. Is this a deliberate decision to touch on the nostalgic?

The use of the camcorder is nostalgic to a point. It’s referenced quite a lot in the film. The other artist accuses my character of being nostalgic. It’s a deliberate aestheticization and one that could be nostalgic. But then again, my character retorts “There is no neutral setting. Everything is imbued with ideologies and implied eras.”

Does this function in the same way as the first room’s sculptures that point to the fetishisation of painting?

To a degree. Within the film, there are ideas of the fetishisation of the working class as being simpler and ‘salt of the earth’ myths. There’s also the idea of the fetishisation of urban decay and this somehow being more authentic. So the film questions this notion of the working class or this nostalgia of the past or the 90s as somehow more authentic. But authentic of what? We don’t know. They are linked, this fetishisation of the past and this fetishisation of poverty. This comes from the idea of ‘the Other’ as being somehow authentic, more real or even exciting. So there are some certain threads of thought that link them together.

A lot of your work is characterised by a dry humour and self-deprecation. Do you think that’s a necessary tool? If your work didn’t have this self-referential element, do you think it would be less successful?

It’s self-referential only up until a point. The idea of the self that I play in my work draws on my biography but isn’t myself. In the Ocean Estate film, I play a parody of myself minus any redeeming qualities. I don’t know anyone who would actually talk in that way to the interviewees. Humour is used as the sugar-coating to a bitter pill allowing people to let their guard down and feel they are not being directly preached to or judged in themselves. I used myself or a version of myself as a vehicle to critique my audience, a certain middle-classness or the self-righteous presumptions of the loosely Left arts intelligentsia who fancy themselves being lefties but are actually often naive, classist and patronising etc. So by performing some of the things I want to criticise, it lets people laugh at me and then hopefully recognise elements of themselves or the world they live in. This is a way to criticise my presumed audience which is usually middle class kids like myself. I found if I am ruthlessly and relentlessly taking the piss out of myself, it gets my foot in the door.

Do you see your work as political?

Yeah. There’s a thousand different types of politics: capital-p Politics, personal politics, relationship politics between me and the people in the room, politics of how we view ourselves as a demographic, who you vote for politics. Not every piece necessarily illustrates a concrete politicised doctrine. It could be political by trying to unravel some of the hypocrisies of the supposed political.

Then would you say you’re trying to enact some sort of change through your work? Do you think that’s possible?

I don’t think artwork has to be teleological in having a fixed outcome and that if you can’t notice or measure the change, it’s therefore a failure. I don’t think the point of artwork is necessarily to change the world, just as the point of music isn’t necessarily to change the world. Hopefully it enriches the world which I guess in some ways might change it. In many ways, my artwork is there to change me and it’s through making the artwork that I learn things about myself and the world. It’s an excuse and a vehicle and an alibi to meditate on the world. The first thing that my artwork’s going to change is myself and my relationship to my community, my peers, my parents, authority, government etc. Perhaps in many ways, I’m talking to myself and thinking through the issues that I find complicated and annoying and niggling. There are overt political sentiments that are addressed in my work but I don’t think that’s where the merits of the work lie. I don’t think overt politics – i.e. criticising gentrification – is the most interesting element because for the most part, people in the art world agree with me and know all these facts probably better than I do.

Do you think an ambiguous position to this is important?

I don’t believe in perpetual ambiguity. There can be things that are undecided but I would urge myself and the audience to take a position and resolve these. I think ambiguity in contemporary art is a little bit overused and abused and can quickly descend into vagueness and non-committal.

Why is being committed important?

Because sitting on the fence is uncomfortable. I don’t believe in blind commitment but I do believe in resolve and agency and change. I don’t think the goal of the artwork is to change the world as if I’m some hero artist single-handedly taking down capitalism. If anything, I think I’d much rather take the piss out of that heroic demeanour that some people (some liberals/artists) assume of this self-flattering grandiose idea of the hero. I don’t know if that makes the world a better place or changes anything.

What do you think of the artist’s role (if anything) in the 21st century?

I think unfortunately art is becoming more and more a luxury only affordable by a few: as art schools become more expensive, arts funding dries up and cities like London get more expensive. Artists can also be the vanguard of gentrification which is a problem, although I think they get a bit too much slack for that than they deserve. I can’t prophesize about the future of the 21st century and art’s role. I’m not entirely convinced art’s role has a goal. I don’t know if it is a goal-oriented, teleological process that’s only merit is transforming the world. We all love music, our experience of music and having it in our lives probably changes us but it’s very hard to say how. Some music might be more political. My first introduction to politics as a young teenager was listening to Rage Against the Machine which sounds sort of twee and naff now. But I always remember they broke up because the lead singer thought it was becoming too much about the music and he wanted to become a political activist. I thought it was a shame he never knew he changed or radicalised me and probably thousands of other young teenagers. He couldn’t count or quantify it. It’s immeasurable.