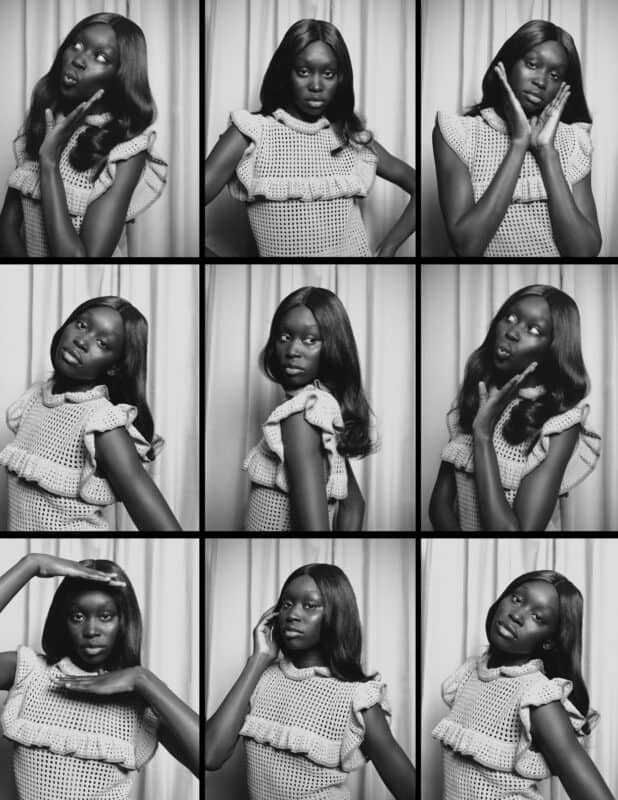

Kara Walker at work. Photograph: Ari Marcopoulos

A certain set of expectations attend any exhibition of the work of Kara Walker, the 47-year old African American artist whose tough-minded, incendiary work on the gulf between black and white in an enduringly racially polarized America shakes even the heartiest of souls.

That being so, The Ecstasy of St Kara, Walker’s current exhibition of new work at the Cleveland Museum of Art, doesn’t disappoint. Big, bold drawings in graphite and charcoal fill the two rooms here, offering a bleak catalogue of ghastly degradation: The Republic of New Africa at a Crossroads, a colossal two-panel piece invoking the name of an idealistic black separatist group, in which bright terrors – a bleeding womb, Confederate flags tinged in blood – emerge from a roiling gray fog; or Easter Parade in the Old Country, a vast triptych that culminates in an African woman, locked in an iron collar, being led by a chain in the hands of indifferent white man, her baby dragged along behind her.

Even so, it’s not the Walker most of us have come to expect. The artist became an instant sensation back in 1994, with a work called Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War as it occurred b’tween the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart. When it appeared at the Drawing Centre in New York, audiences were struck by the rift between the form Walker had chosen to use – a tableaux of otherwise folksy cut-out figures in silhouette, a convention tied to her chosen era, the antebellum American south – and the content with which she filled it: rape and dismemberment of African American women and children by cheerful white masters, black men lynched and dangling from tree branches. It was as though Uncle Remus had run headlong into Clive Barker, with Ku Klux Klan grand wizard David Duke serving as creative consultant.

The work made Walker an instant star and, in 1996, became one of the youngest ever recipients of a MacArthur Foundation genius grant (she was 27). It also set the frame for what would become a decades-long exploration of her signature form – a litany of terrors underpinning contemporary American life, cast deeply in shadow but screaming out loud to be heard.

The Ecstasy of St Kara both extends and deepens that mission. The show evolved from a recent fellowship at the American Academy in Rome, where she was the Roy Lichtenstein Artist in Residence. The residency, Walker writes in an introductory essay to the show, gave her some welcome distance from the accruing catastrophes of American race relations in recent years: the growing list of young black men killed by police, the increasing suspicion of Black Lives Matter, which she calls “the current incarnation of a civil rights movement”.

Walker began making all the work here in the early part of this year, when the spectre of a Donald Trump presidency seemed distant and laughable. With Trump now assembling his cabinet – and placing prominent opponents to civil rights, such as proposed attorney general Jeff Sessions, among them – Walker’s work here now has an aura of eerie prescience.

Shaken by the regularity with which young black men were dying at the hands of the police, the artist seized on the anxieties of a frenzied nation. Walker chillingly suggests here that the upsurge in violence came not in spite of Barack Obama’s rise to power, but because of it.

“I fear that Michael Brown and Tamir Rice and all the rest were killed as proxies for the Black President,” she writes, citing two prominent names in a growing litany of killings. (Brown was the 18-year-old whose killing by police touched off the Ferguson riots in 2014; Rice was the 12-year-old Cleveland boy killed by police while holding a toy gun that same year.) The rise of Trump, with his propagation of the “birther” notion – that Obama was not American born, but rather an interloping foreign Muslim – do little to dispel Walker’s theory.

In Cleveland, Walker’s master narratives, involving the grotesque horrors of slavery and the unbridgeable social chasms they’ve carved in the here and now, fill the two big rooms with roiling unrest. At any given moment, the work discomfits in simultaneously the best and worst ways, amplifying the grotesque origins of contemporary America to near deafening. (Walker’s shows almost always come with warnings about sexual and violent content and age-appropriateness; The Ecstasy of St Kara is no exception.)

Significantly, Walker’s signature cutesy cut-out style, which dared viewers to see the horrific scenes she portrayed as an insignificant sideshow to the mainstream, heroic notion of America as the guardian of liberty for all, is absent, the artist choosing instead a critical stance unleavened by conceptual frame.

One colossal drawing, Securing a Motherland Should Have Been Sufficient, lays it plain. It depicts a black woman – topless, intense, fretting angrily – pounding nails into the skeleton of an enormous ship. The reference, to Noah’s ark, is explicit, but Walker freights it with ugly realities. Outside the structure, heaps of bodies both living and dead are denied the vessel’s promise of salvation, an ugly metaphor for the shabby idealism of the central broken promise of American democracy.

With incendiary rhetoric coming from the country’s highest office – on mass immigrant deportations, a Muslim registry and, during his campaign, the president-elect’s musing that he might have his attorney general investigate Black Lives Matter as a domestic terrorist organization – Walker’s work here seems less conceptually critical of a broken social order than clear-eyed in its suddenly realistic fear of what may be to come.

“We are living in a nihilistic age, a vacuous blank space that opens up when hope is replaced by fear,” she wrote, with an alarming clairvoyance. On a nearby wall hangs a piece that brings it together: a tombstone, surrounded by thickets of dark, the initials “BLM” inscribed on it. A silhouetted black head perches on its peak. Whether it refers to the movement or the sentiment it describes – in America, more tenuous now than in decades – is left for you to decide. One thing remains certain: in the coming darkness, Walker’s work, sadly, is more relevant, and necessary, than ever.

- The Ecstasy of St Kara continues at the Cleveland Museum of Art to 31 December 2016

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.