FAD caught up with one of the most significant figurative painters of his generation Jonathan Wateridge to ask about his work ahead of his new exhibition with Pace London and HENI.

1 Can you tell us about the process you went through to create your paintings.

My process for each project has been pretty similar for a number of years now. After a period of research and reflection on what it is that I’m trying to address with the work, I choose the location in which to set the paintings. That site is then constructed as a large scale set inside my studio. Actors are cast, costumes sourced and a film shoot is organised so that I can stage the performers or improvise with them in order to build up a body of reference imagery, from which the paintings are then developed.

Two main factors contributed to the origins of this current exhibition, Enclave. The first grew out of a previous body of work called Monument, which was exhibited at Wilkinson Gallery in London in late 2014. The show was a response to a few months I spent in Los Angeles and included a number of paintings of what I viewed as ‘symbolic surfaces’, such as driveways; gates; or a security lit suburban lawn. These paintings alluded to issues of exclusion and access; and also the public and the private.

I subsequently realised that some of my fascination with these parts of LA was because they reminded me so much of areas of the city I grew up in – Lusaka, Zambia. I’ve never been particularly interested in addressing my own biography but I found myself thinking more and more about this connection.

The other factor was the growing tragedy of the migrant crisis over the last couple of years, and more specifically the sense of collective amnesia in the UK as to how these issues had reached this point. I realised that depicting elements of my own past could become a way of tangentially dealing with a wider set of issues concerning the west’s relationship to the post-colonial world.

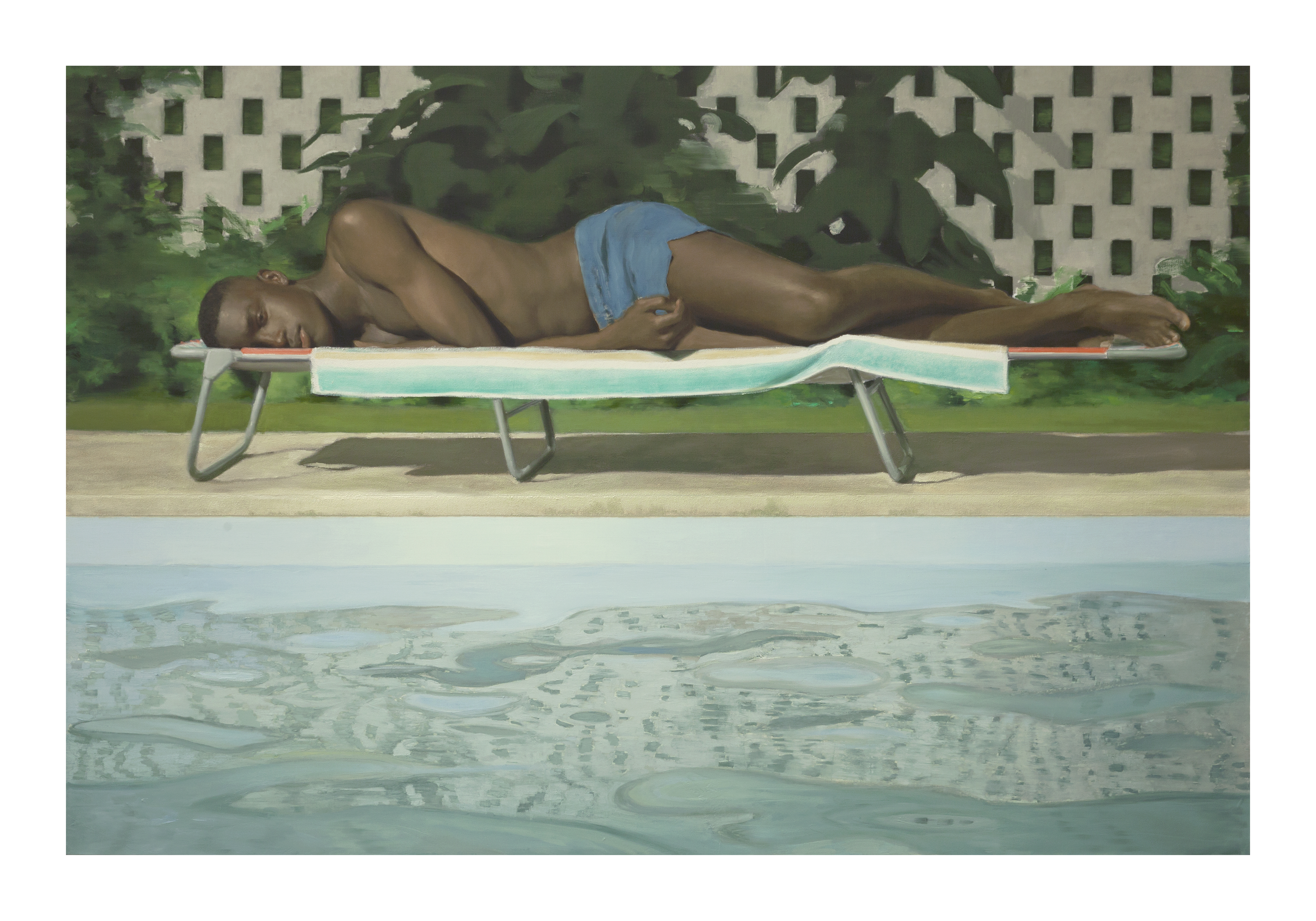

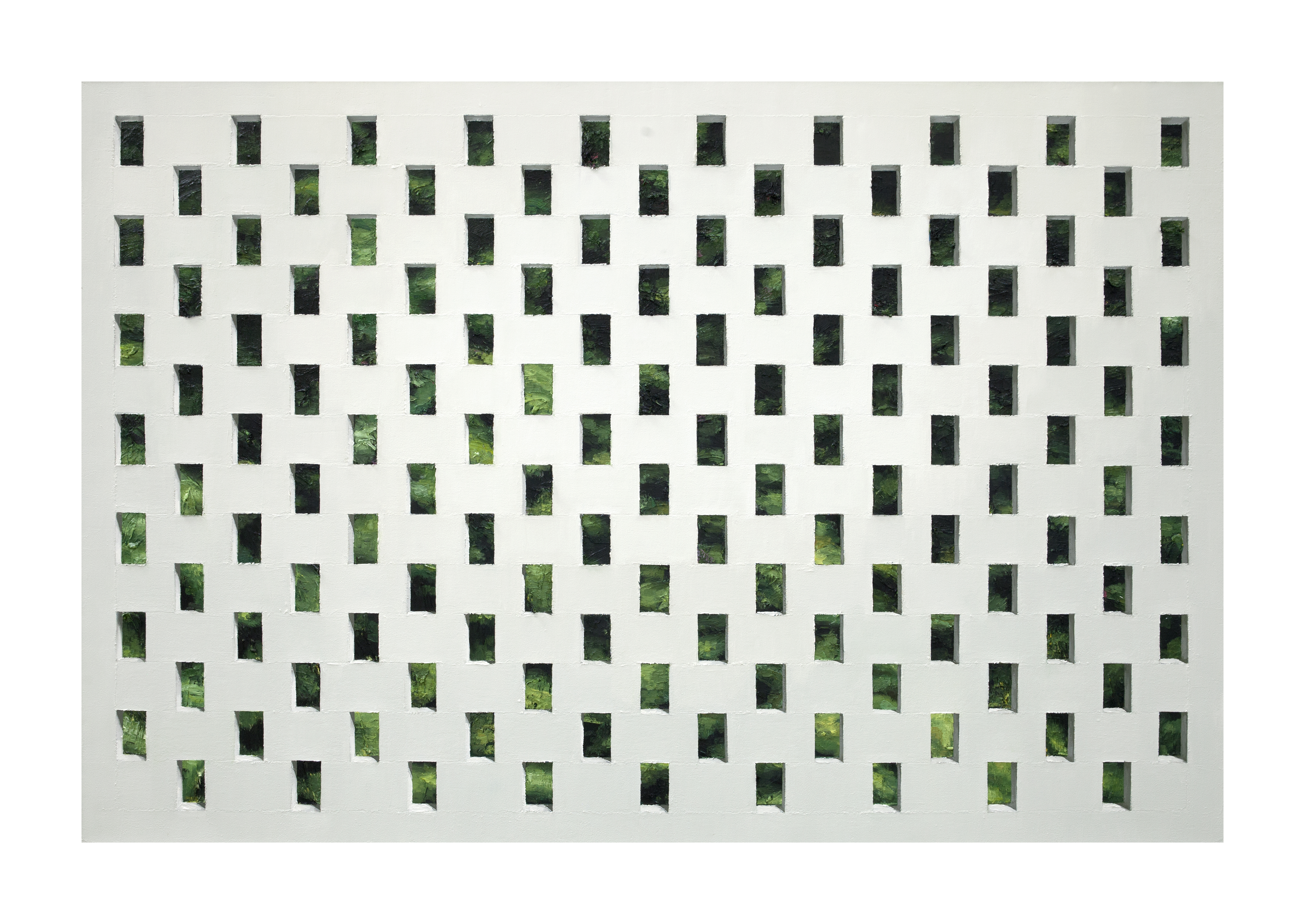

The environment seen in the paintings is a set based on my childhood garden in Zambia. It had an open breeze block perimeter wall, a style which was very common at the time. It soon occurred to me this could be a subtle but resonant motif to run throughout the paintings and that the garden itself could act as a metaphorical site.

The sub-text to this work has perhaps been made more overt by the disturbing tones of the political debate both in the UK and throughout the west in the last year. As I was developing the paintings, I had no idea that the rhetoric of both Brexit and Trump would mean that the notion of ‘walls’ in relation to access to the western economic ‘enclave’ would go from being figurative to frighteningly literal!

2 Is paint the perfect medium for your work?

I believe that you end up becoming the artist you have to be, not necessarily the artist you want to be. I’ve interrogated my reasons about whether to paint or not for most of my adult life. In someone else’s hands the ideas that I’m trying to explore in this exhibition might be better expressed through film or performance or photography. But I can only speak for myself and nothing seems to engage me more than the conceptual, visual and material problems involved in trying to make a successful painting, and particularly within a contemporary art context.

Also, I’m not just interested in image making per se. My work has increasingly dealt with the material aspects of how the painting is constructed; it’s surface, paint application, formal organisation and the way that it relates to the history of the medium.

And I like that painting resonates across images rather than through them, as film or video often does. I like that painting silently inhabits a wall and doesn’t dictate the terms of your attention as a viewer and it can be read very openly in that way.

The cultural influence of new technologies has also been good for painting, in that subjectivity has been reintroduced to image making at a fundamental level. Of course, it was always there but until recently, the alchemical purity of the photograph has given images a degree of ‘honesty’ most other mediums could never claim. However, the inherent ‘constructedness’ of new media imagery has changed the conceptual landscape in such a way that it has conferred a degree of renewed legitimacy on painting. Ironically, the weird, odd, made-ness of painting and its very obsolescence is exactly what makes it interesting to be exploring right now.

3 Should people be more aware of what is going on?

I think paintings work best when they approach things obliquely. I’m interested in the resonance and echo of ideas, as opposed to the confrontational. Too direct an approach closes down an openness of reading in the work and also risks being too didactic or polemical. I just want to do enough to disturb the waters and to make things feel somewhat strange or uncanny and in doing so, raise a few questions.

I also think it’s fine if someone wants to view something on a purely aesthetic level. If they want to look further into the work and explore other facets, whether that be narrative or social politics, that’s fine too. In addition, supplementary information is always valuable to the reading of any work of art, whether it be a Bruce Nauman or a Botticelli. And I don’t have a problem with that. Given that we now experience the world in hugely complex and multifaceted ways, the idea that an object or painting should contain everything you need in order to fully access it, for me, feels a little too singular and absolute.

4 How long did the exhibition take to put together?

I started the paintings in February of this year but prior to that there’s the whole process of conceiving the project and then set building; casting actors; doing the shoot etc. Once that’s all completed, I then edit through reference material before making a number of studies. So all in all, from conception, I guess the project has taken around 18 months so far. It also overlapped with work from another project that was showing in Berlin earlier this year, so it’s fair to say it’s felt like a pretty busy time – not that I would ever complain about that, I like to be working.

5 What was Glasgow like for you in the 90’s?

It depends on whether you’re referring to Glasgow as a city, which is a fantastic place or the Glasgow School of Art, which I have a lot of affection for but it’s safe to say I didn’t have a particularly happy time of it when I was there.

I hadn’t done a foundation course and went straight into the Glasgow School of Art 2nd year in 1990, knowing absolutely nothing but totally convinced that I wanted to be a painter. Within six months, I had stopped painting and didn’t pick it up again for over 15 years.

At Glasgow, I soon came to believe that painting was a moribund and ineffective way to be making work at the close of the 20th century. In general, the early 90s weren’t a great time to be making paintings from a critical and curatorial point of view (indeed figuration, and realism particularly, is still viewed as problematic by many) but this wasn’t the case in the painting department in Glasgow at the time and I had to really fight to make conceptually based work in that environment. Things changed for the better soon after I left but I had already grown so disillusioned that I never graduated. The next few years for me were very hard, as I didn’t really know which way to go. This was also all pre-internet so, as a 21 year old, your sense of what was creatively out there wasn’t as easily accessed as it is now.

I thought film was a possible route but I’m not particularly technically minded and I like being on my own, so I found the more public process of making film very difficult. Not to mention the sheer financial and logistical difficulties of getting projects off the ground.

6 Memory, is it real?

Philosophically that is probably too big a question to answer here! So instead, I’ll assume that you mean that within the context of the exhibition? In that case, memory isn’t necessarily false but it’s certainly constructed.

The idea of ‘constructedness’, of things being fabricated or somehow false, is a crucial part of my process. The physical reconstruction or reconfiguring of an initial source, via the sets, is a way of applying a sense of remove from the idea of a ‘true’ origin or referent.

Memory also depends on whether you’re referring to personal, biographical experience or collective and cultural memories. We increasingly experience the world through the same relentless barrage of cultural imagery and, as I don’t view my experiences as particularly unique, I always assume that if I’m reminded of something whilst planning an image then a potential viewer will also recognise it.

Finally, memory is also related to dreams. And I try to generate an intensity among the paintings that is somewhat dreamlike. In dreams, meaning isn’t necessarily fixed or transparent and is open to the symbolic. In a similar manner, I hope it becomes apparent that within Enclave, the ‘swimmer’ can stand for something much wider than the immediate image of a man sunbathing by a pool.

Jonathan Wateridge ‘Enclave’ 6 – 10 Lexington Street, W1F 0LB On until – 13th November 2016

www.henipublishing.com/-jonathan-wateridge-enclave/

About The Artist

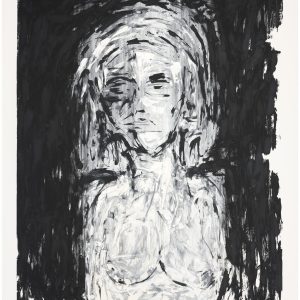

Jonathan Wateridge (b. Zambia 1972) is one of the leading figurative painters of his generation. His work explores an entirely constructed world of ‘non-events’ in order to raise questions about how one frames and understands notions of the real. His work of the last three years has witnessed an increasing interplay of figurative motifs with more formal abstracted painting in a manner that explores the nature of the medium and its history in relation to the shifting imagery of contemporary life. A student of the Glasgow School of Art in the early 1990s, Wateridge abandoned painting until 2005 when he embarked on a series of dramatic disaster paintings that fused B-movie aesthetics with the romantic sublime. These paintings were followed by the Group Series, a collection of faux historical tableaux depicting commemorative gatherings from astronauts to Sandinista rebels which were included in Newspeak: British Art Now at the Saatchi Gallery in 2010; and Another Place, a series of seven monumental paintings pertaining to a fictional disaster movie that explored the artist’s filmic memory of the city of Los Angeles, was exhibited at the Palazzo Grassi, Venice in 2011.

Subsequent exhibitions include Inter + Vista, an exploration of contemporary vignettes via figurative and formalist practices, shown at L + M Arts, Los Angeles in 2013 and most recently ‘Colony’, a series of paintings depicting the conditioned movements of a group of young adults ensconced in the setting of anonymous apartments, exhibited at Galerie Haas in Berlin in 2016.