The London art scene is massive and overwhelming. Out of hundreds of galleries and thousand of people who work in them, how do you know where to go and who to listen to?

We asked a few hundred art professionals, curators, and artists to name their favourite galleries and we came up with a list of 70. Luckily for us, many museums and galleries were available for interviews.

This interview was conducted in 2015, it took a year to publish because it turns out it’s a lot harder to liaison with 70 galleries and their PR agencies than we originally expected. All the anachronisms were kept to illustrate just how fast paced the London gallery scene is, some people we interviewed no longer work at the same galleries, and some galleries no longer exist in the same form they did last year.

We wanted to share the knowledge with as many art professionals as we could so we are sharing 20 condensed interviews with Fad’s readers. The full lengths interviews are available in the book ‘Who to Know in London?’

This is the 17th interview out of the series of 20.

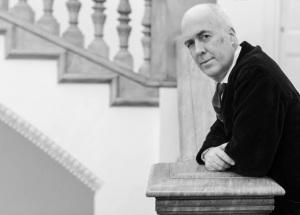

Tell us about your background and how you set up Raven Row?

I got into the art world slightly by accident although I was always interested in the modern art I grew up around. Through a bar that I was trying to set up in the early 90s I became friends with an art student at Goldsmiths College who was part of a small arts organisation called Rear Window. This was an exciting time for art in London. As a result of the property crash, many buildings were vacant and there were a lot of enterprising students using them for exhibitions, which is what Rear Window did.

I became involved with Rear Window but really only as its funder. I never thought I could become a professional in the art world – it didn’t seem there was a place for me as I had neither the psychological capabilities of a commercial art dealer nor the academic background of a fully-fledged curator. But after Rear Window changed shape and became a new organisation called Peer, which still exists, my involvement deepened. When I proposed a project in 2001 about a then obscure Italian artist from the 60s called Francesco Lo Savio my fellow board members suggested I took it on. I ended up editing a monograph on Lo Savio as none existed. To contextualise the monograph, I organised a small exhibition for which I found a first-floor space in Fitzrovia. I ended up keeping this on as a project space for two years, which I named after its address, 38 Langham Street. There I did historical shows as well as projects with young artists. Some of these – Gareth Jones, Hilary Lloyd, Nils Norman, and Pádraig Timoney – have come back into Raven Row’s programme.

What do you think it takes to make a critically acclaimed art institution?

I think it’s crucial to have your ears to the ground, to be able to recognise or even anticipate what might be relevant to artists and contemporary culture. The older one gets the more difficult this can become.

What is your target audience and how do you appeal to them?

The kind of art Raven Row exhibits is inevitably of interest to a fairly specialist audience. It’s much easier to accept and accommodate that situation here than for publicly funded institutions. Although I try to avoid art speak wherever possible, I can address an audience assuming they are already interested. Raven Row doesn’t have a marketing strategy, so people know about it mostly through word of mouth.

How many people work for your gallery and what are their roles?

Raven Row can be run less bureaucratically than publicly funded institutions, and there is less administration involved. The team here is small and focused on exhibitions. Apart from myself, there are three other full-time members of staff, although there are some key part-time roles and plenty of others working as technicians and gallery assistants to look after the exhibitions when they are open.

How has the art landscape changed since you opened?

London is in danger of becoming completely unaffordable to artists and workers in the cultural sector. Meanwhile, the market is getting an ever tighter grip on activity within the visual arts especially now that public funding is being drastically reduced. Nevertheless, it’s amazing how much grassroots art activity there still is, and that’s not just concentrated in the East End but has become much more dispersed. I worry though that with the high costs of living in London and the increasingly adverse funding conditions this situation might not last.