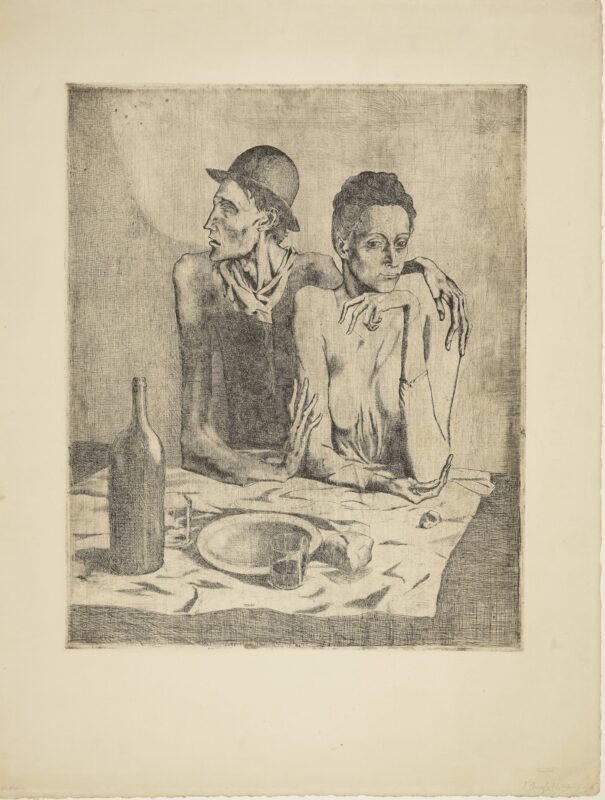

The golden rhinoceros and other figures were marginalised by the apartheid government because they contradicted its narrative of an empty land. Photograph: Stefan Heunis/AFP/Getty

One of Africa’s greatest treasures, the 800-year-old golden rhinoceros of Mapungubwe, is to leave the continent for the first time as part of a British Museum exhibition exploring 100,000 years of South African art.

More than 200 exhibits will be displayed at the show, opening in October, but securing loans of the rhino and other extraordinary gold objects is particularly significant.

“The curator in charge of those objects has called them Africa’s crown jewels and I think she is right in saying that,” said John Giblin, head of the British Museum’s Africa section.

“I got to see them for the first time last year which was incredibly exciting, and to bring them here, for them to be part of a story for new audiences, is a fantastic thing.”

From 1220 to 1290, Mapungubwe, near the border with present-day Botswana and Zimbabwe, was the capital of the first kingdom in southern Africa.

The gold foil figures, discovered in royal graves at Mapungubwe, were actually found in the 1930s but were denied, hidden and marginalised by the apartheid government because it contradicted its racist narrative of terra nullius, the myth of an empty land, which was used to legitimise white rule. The objects testify to the sophisticated, settled society which traded gold and ivory with China, India and Egypt many centuries before settlers from Europe arrived.

The British Museum is borrowing golden figures of animals of high status, such as a cow, a wild cat and the rhinoceros; and objects associated with power including a golden sceptre and golden bowl. The only one to have ever left South Africa is the bowl, which underwent a year of conservation work at the British Museum – a connection which has helped to secure the new loans.

The golden rhinoceros, described as the South African equivalent of Tutankhamun’s mask, has taken on added significance in South Africa as it is now the symbol of the Order of Mapungubwe, South Africa’s highest honour that was first presented to Nelson Mandela in 2002.

Giblin said they were delighted to have the golden figures which “have become some of Africa’s and arguably the world’s most iconic sculptures”. But they are only one part of a show that tells the story of South African art, which stretches back 100,000 years.

One of the oldest objects will be a 77,000-year-old shell bead necklace discovered at Blombos cave in the Western Cape. It makes the region one of the earliest symbolic cultures anywhere in the world, going back much further than what we know was happening in Europe.

“People used to think that real artistic practice began in Europe, 30,000 or 40,000 years ago; they typically cite the French cave paintings,” said Giblin. “These kinds of finds really push that back a lot earlier, and it is only really in the last couple of decades that the tradition has been identified, so it is a really nice time to be telling this story.”

The exhibition will be divided into sections which will also include the influence of European and Asian settlers and resistance art from the apartheid era. Each section will also feature work by contemporary African artists, which the museum has been collecting for over 20 years, providing fresh perspectives on South Africa’s past.

One of the most recent acquisitions is a two-metre wide textile called The Creation of the Sun (2015), a collaborative piece from Bethesda Arts Centre, made by descendants of South Africa’s first peoples.

There will also be contemporary art loans including a self-portrait by Lionel Davis, a political prisoner under the apartheid regime, and a 3D installation by Mary Sibande.

Giblin said there had never been a UK exhibition on South African art which had such variety and he hoped that it would illustrate its remarkable diversity. “What underlies the story is that South Africa’s art heritage is the art heritage of many: many different peoples, whether South Africa’s first peoples, San bushmen or Khoekhoen herders. Or the Bantu language speakers who arrived around 500AD and are responsible for the Mapungubwe gold objects, and their descendants who make up the majority of black South Africans today.

“Or European and Asian people who arrive from the 17th century, including Dutch, British, Indian, Indonesian and Chinese and all of their descendants.”

Hartwig Fischer, the museum’s director, hoped it would “challenge audience preconceptions in the way our visitors have come to expect from a British Museum exhibition”.

• South Africa: the art of a nation, sponsored by Betsy and Jack Ryan, is at the British Museum from 27 October 2016 to 26 February 2017.

• This article was amended on 9 August 2016. An earlier subheading incorrectly described Mapungubwe as the site of the first African kingdom. The article was also amended to correct a description of a 77,000-year-old necklace and make clear the curator is female.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.