You don’t think of William Eggleston as a portrait photographer. He is known for his colour shots of the everyday American South in the 60s and 70s – slow-time smalltown scenes with nothing in particular happening, buildings and signage, fields beyond the roadside. But he snapped plenty of people, too – not because they happened to wander into view, but because he was interested in them. And although the saturated film colour of the time seems to permeate his photography, in fact he was a tinkerer who pushed what was technically possible with his cameras, and so his portraits span very different looks. The National Portrait Gallery (NPG) show brings all this out, and several masterpieces.

In the early 1960s, Eggleston was doing strange things in black-and-white. He acquired police surveillance filmstock that revealed things in low light, but, working in pitch darkness, he had to cut it length-wise and make sprocket holes so it would fit into his miniature Minox camera (the one spies used in cinema and indeed reality, at the time). A picture of his mother sitting in bed steps into her privacy with stealth. Later, he would experiment with motion film, even loading infra-red film in a Sony PortaPak when he probed into the dim world of Southern folk hanging out at night. The NPG shows some footage from his legendary 1974 documentary Stranded in Canton – when ‘Lady Russel’ lights a cigarette, the ball of white light from the frame illuminates the intimate concentration on her ghostly face in a way impossible with conventional film.

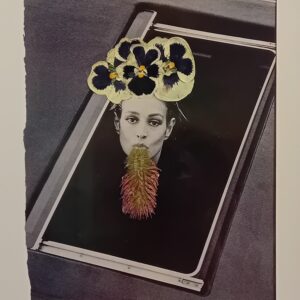

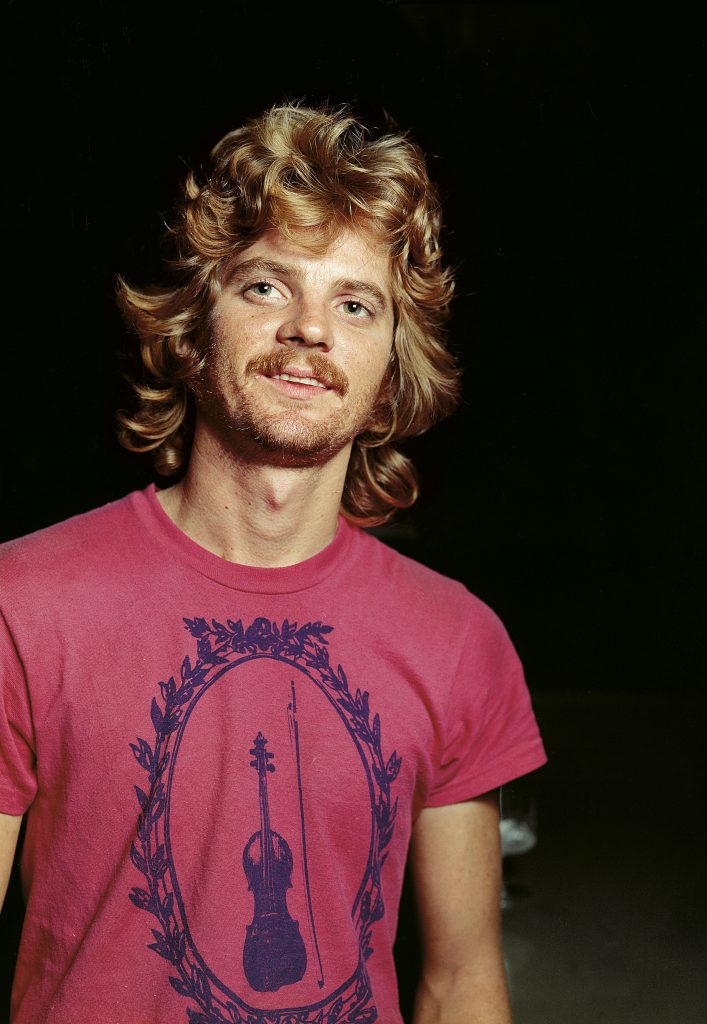

But from 1965, Egglestone had started shooting in colour. His artisan approach is here too. He developed pictures using a laborious dye transfer method in which three negatives of an image each shot in a primary colour are processed and precisely realigned for perfect registration. The resulting richness is extraordinary, as you can see in Eggleson’s mid-70s shot of dancer Marcia Hare in a flower dress, lying on grass like Ophelia in water. The dramatic frozen motion of her in an adjacent black and white picture could not have a more different mood. And although Eggleston photos can sometimes seem to feel almost soft-focus, he also pioneered an ultra-sharp, forensically realistic look in portraits. But for the distinctly 70s styles in dress and hair, those he shot of nightclub goers in 1973-4 feel contemporary. Dane Layton in 1973 could just as well be in a hip Brooklyn combo gigging today.

Untitled, c.1975 (Marcia Hare in Memphis Tennessee) by William Eggleston, c.1975 ©Eggleston Artistic Trust

Untitled, 1973 – 4 (Dane Layton) by William Eggleston, 1973 ©Eggleston Artistic Trust

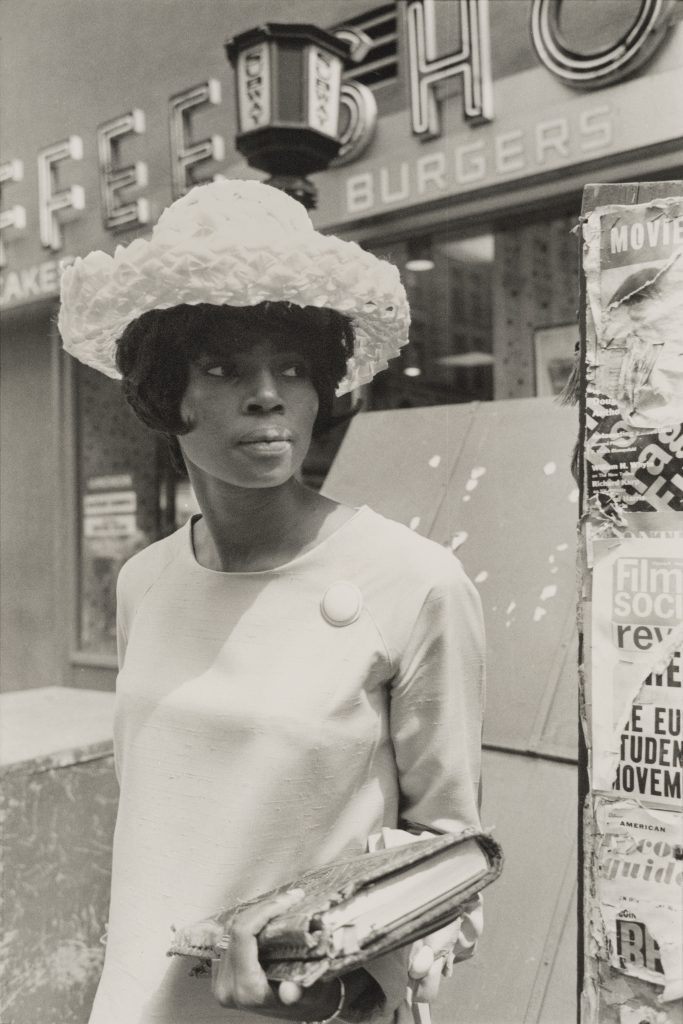

The elephant in the room in the American South, especially in Eggleston’s time, was race and the civil rights movement. He claimed he wasn’t interested in political documentary, but since he shot what he saw, there is certainly a ‘no-comment’ insight into race. The four black girls, three of them toddlers, returning his look from the edge of a vast platation field, speak volumes. Jasper Staples, a black man working for Ayden Schuyler Snr, echoes the stance of his distinguishedly-suited employer as they stand by the latter’s boxy car, is calm but sharp social commentary. The black woman outside a diner in his 1960s black-and-white shot may not have got through the door just years earlier – yet now she’s confident enough to look as groovy and cool as any Motown star.

Untitled, 1960s by William Eggleston, 1960s ©Eggleston Artistic Trust

Sometimes, a celebrity would be the subject, but there was no fussing to arrange the shot. For example, little more than Dennis Hopper’s hair and hat as he is at the wheel on a sun-glared dusty drive are enough to place you there with him. Eggleston’s girlfriend Viva (who he met at Warhol’s Factory, a place he seemed not to have cared much for), sits blank and tired by a roadside. He was always shooting the person, not any fame or associations. Some had none beyond state or county lines. Local dentist TC Boring stands naked in his house, amidst words he had spray-painted on his own walls. There’s something Twin Peaks about it. Later, Boring would be found in the burnt-out house with an axe in his back. As with Eggleston photographs, there was no explanation.

Untitled, 1970 – Dennis Hopper by William Eggleston, 1970–74 ©Eggleston Artistic Trust

Eggleston had a talent for capturing mood, mystery, and the moment. His portraits add personality and often intimacy. William Eggleston Portraits brings out yet more dimensions to those the most enigmatic masters of photography is known for. And it should remind contemporary photographers that photography is a craft, and marrying an instinctive eye to mastering the technicals pays dividends.

William Eggleston Portraits at the National Portrait Gallery, London is organised with the support of the William Eggleston Trust and runs until 23rd October www.npg.org.uk