Is art a modern religion? It’s like the joke about sex being dirty: it is if you’re doing it properly. At its most powerful, art can offer a cosmic sense of place that for many of us religion no longer provides. The other day, I visited the latest incarnation of the Mark Rothko room at Tate Modern. No matter how much Tate moves it about (right now it’s with Monet), this imposing installation of black, purple and red paintings of dark portals always takes me out of myself and makes me think about the bigger things.

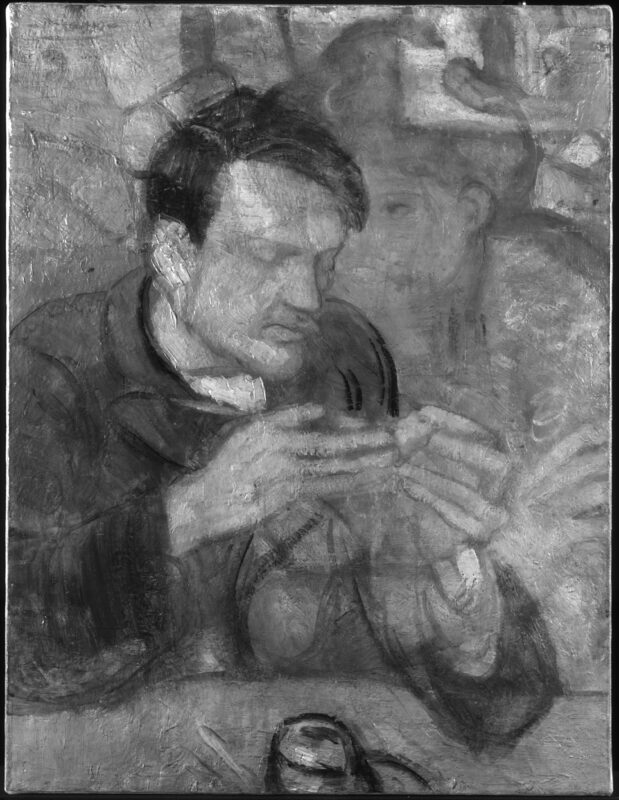

Art resembles medieval Christendom in another way: we revere not only artists but also their relics. A curious instance of artistic worship is the sale next week by Chiswick Auctions of a pair of gloves worn by Francis Bacon. They are painting gloves, apparently, and Bacon wore them when he created one of his most renowned works, his triple portrait of Lucian Freud.

Chiswick Auctions obviously hopes a bit of the price-tag magic Three Studies of Lucian Freud’s conjured when it sold for £89m in 2013 will rub off on the gloves when they go under the hammer. The paint-stained gloves are framed like a work of art and have an estimated value of £5,000 to £7,000. Who would pay that much for a pair of gloves? Quite possibly a Bacon fan with some spare cash. And I would be the last to carp, because relics of artists really are moving.

Last year, I made a pilgrimage to the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice to see a single painting by Jackson Pollock. I was equally moved by the brushes and sticks the artist used to drip and flick paint, still stained with his strong colours. Pollock’s painting gear is a wondrous, intimate record of how he worked. At the Picasso Museum in Paris you can see the chair the painter used as a rest for his brushes. It is kept behind glass, like the precious artefact it is. If Turner is more to your taste, Tate Britain owns not only a huge hoard of his paintings but also his palette and paintbox, carefully preserved since his death in 1851.

Bacon’s gloves are a comparatively humble relic of the Irish-born artist. The Hugh Lane Gallery, in Dublin, has preserved his entire studio behind glass. Bacon’s work space can be viewed in this installation as a paint-spattered reliquary. Is there a connection between Irish Catholicism and this appetite for Bacon’s relics? Regardless, it is fascinating to see – a sealed room haunted by his macabre imagination. And what did you see, Clarice?

Bacon is a living force in art – and the art market. The strangest mementoes preserve artists who many people have long forgotten. I include the sculpture studio of GF Watts, immaculately maintained along with other souvenirs of this Victorian artist at the Watts Gallery in Surrey, as well as the perfectly conserved flat in which Gustave Moreau lived that adjoins his studio in Paris. I am a big Moreau fan, so I love it, but when I took a group to see it, they were aghast at this bizarre remnant of symbolist Paris. Other relics of the 19th-century avant garde include some Moroccan musical instruments collected by Delacroix.

Artists keepsakes go back to the Romantic age and reflect our romantic belief in artistic genius. Yet the greatest ones are works of art themselves. Michelangelo’s sculptures, their unfinished surfaces pockmarked by his chisel, are evidence of genius at work. Personally, I feel a religious awe at these tangible marks of Michelangelo’s living presence. Great artists are immortal, and their physical being is held in their art like a face on a shroud.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.