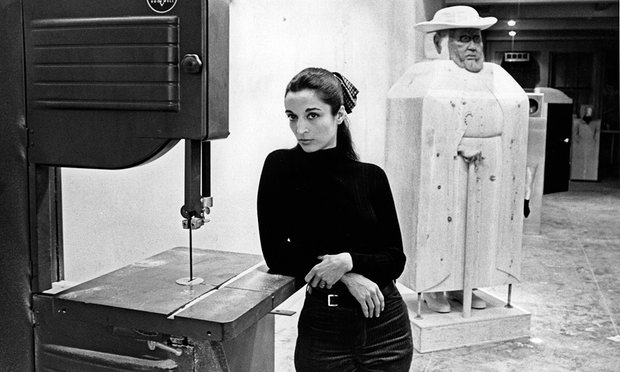

Marisol in 1968: ‘the first girl artist with glamour’ Photograph: Jack Mitchell/Getty Images

The artist Marisol, who has died aged 85, was perhaps the most underestimated sculptor to emerge in New York in the 1960s – when the rigidities of the postwar avant garde gave way and a pluralistic, hybrid set of styles began to flower. Her deadpan depictions of popes, presidents and her own family, crafted from wood into boxy totems, captivated the art world and enticed the media, too. At the birth of pop, she was as famous and influential as Andy Warhol, and gorgeous, too – “the first girl artist with glamour”, Warhol said. Her art was on the cover of Time; Gloria Steinem profiled her for Glamour; lines for her exhibitions stretched down the block. But Marisol was never comfortable with the media spotlight or the rapacious art market. At the height of her career she left New York on a years-long travel jag; she made fewer works in the 70s and 80s, and latterly she fell into obscurity.

Though her boxy personages, neither properly flat nor fully detailed, have an instant appeal, Marisol’s art fits awkwardly into the anterior divisions we now make of American sculpture in the 1960s. She studied with Hans Hofmann, who taught so many of New York’s abstract expressionists, but gave up action painting for sculpture. Yet Marisol was not quite a pop artist, despite her use of hot colors and depictions of the Kennedys and John Wayne; she was too interested in the private, enigmatic, and self-expressive for that. Robert Rauschenberg’s combine paintings are a clear influence, and she had a neo-dada streak that led her to incorporate found objects such as shoes, doors and televisions, often recovered from the trash. Neon and aluminum, too, worked their way into her art as minimalism came to dominate the New York scene. And sometimes she affixed her sculptures with photographs – a foretaste of the contemporary, media-breaching sculptural practice of Rachel Harrison or Isa Genzken.

“In the 60s, the men did not feel threatened by me,” Marisol said later in life. “They thought I was cute and spooky, but they didn’t take my art so seriously.” Nevertheless, she was a leading artist on the roster of the prestigious Sidney Janis Gallery in New York and was one of only four women among the 150 artists at the Documenta of 1968. She approached the gender inequities of the art world not with feminist passion, but with a calculated silence, using mystery and aloofness to affirm her position as a serious artist. As the artist Carolee Schneemann says, “Marisol was an important figure, subtly affecting change by her silence and the particularity of her position … She was the female artist star of pop art, [but] she dramatized it in a very subdued way, through her intensely quiet manner.” She could spend hours at a lunch or an exhibition opening and never say a word. So, too, her art: the sculptures bristled with personal significance and careful craftsmanship, but they withheld everything. Even the sculptures that depict the artist herself – such as her great Self-Portrait Looking at the Last Supper, in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art – give away little.

Last year in New York El Museo del Barrio, a museum devoted to Latin American art, presented a smallish but still welcome retrospective of Marisol’s sculptures and works on paper, on tour from the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art in Tennessee.

But in the home town she loved and often escaped, her most enduring work is a late one: the American Merchant Mariners’ Memorial, completed in 1991 and positioned at the lower tip of Manhattan in Battery Park. The memorial sits on a pier, and features an abstracted, rounded bronze ramp – a sinking ship, torpedoed by a U-boat – from which one sailor calls for help and a second reaches down into the water. Half-submerged, bobbing above and below the waves, is another sculpture: a bronze hero reaching for safety, his arm stretching towards the ship and not quite making it. Like Marisol herself, the sailor sometimes disappears from view, but he is always there – solid, steadfast, and unafraid.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.