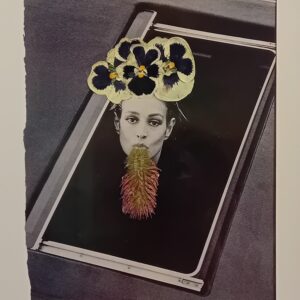

Sterling Ruby at Sprüth Magers gallery in London. Photograph: David Levene for the Guardian

Ten years ago, Sterling Ruby left art college without his final degree and almost $300,000 in debt. Since then he’s become an art world phenomenon exhibiting his monumental sculptures and diseased-looking ceramics with global powerhouse galleries like Gagosian and Hauser & Wirth, where they have been bought by “supercollectors”, including Hollywood agent Michael Ovitz. And, though Ruby has divided critical opinion, Roberta Smith, art critic of the New York Times, described him as “one of the most interesting artists to emerge in this century.”

When we meet at Sprüth Magers gallery in London, the 44-year-old artist is dressed head-to-toe in distressed denim: jacket, jeans and shirt, all designed by himself. Around him, bleached sweatshirts and trousers hang in a line on one wall; on another, splattered coats are suspended like ghostly hoodies. “I love that the gallery window looks like an old-fashioned storefront,” says Ruby, who has titled this exhibition Work Wear: Garment and Textile Archive 2008-2016. The result is less Mayfair art box, more Hoxton clothes shop after a flood or an industrial accident.

Elsewhere, flattened denim ponchos and dyed textile pieces nod to the tradition of Amish quilt-making that Ruby often cites as a touchstone for his work. Another more obvious precedent is his ongoing collaboration with Belgian fashion designer Raf Simons, ex-creative director of Dior, which has seen the pair launch a denim rangeand create a 2014 fall/winter fashion collection together. It was a catwalk triumph, with Sterling telling W Magazine: “Everybody was standing up, cheering. At that moment I thought, ‘Fuck being an artist — this is wonderful.’”

It is Ruby’s art, though, that has made him rich. Indeed, his output is so prodigious – sculpture, textiles, painting, collage, ceramics – that it is difficult to figure out how he finds the time to make clothes. The answer maybe lies in his psychological makeup. Although calm, thoughtful and charming in person, he is utterly driven when it comes to work. “I was kind of conditioned for failure by my teachers,” he says, smiling. “I remember one of them telling me that, if I wanted to be a serious artist, I’d better resign myself to working in a 7-Eleven and being poor for the rest of my life.”

Ruby works nine to five every day, running from studio to studio. “I’m manic, for sure. I’m always working on several series simultaneously. Right now, I’m making paintings, large flags, tapestries and textile works, a new ceramic series and I’ve started making mobiles.” With his love for acronyms, he has christened one of the new series ACTS, which stands for Absolute Contempt for Total Serenity. The title may or may not be ironic.

An artist who thinks big and makes even bigger, Ruby’s latest studio near Los Angeles spans two acres and includes a 30,000 sq ft viewing room where he can observe the finished pieces made in various vast adjacent spaces: one for drawing, one for ceramics, one for poured sculptures, one for the fabric collages and one for his huge paintings. A 10,000 sq ft storage space houses his ongoing archive.

He is best known for his sculptural works: the giant ceramic “Ashtray” series that look like misshapen remnants from a nuclear accident, and spray-painted stalagmites made from PVC, Formica, urethane and wood. The titles alone – Monument Stalagmite/Headbanger – go some way to evoking their monolithic but wilfully messy presence. Everything he does evokes the actual doing – the visceral struggle to transform these materials into art that is, in turn, transformative. No mean feat in an art world where detachment, irony and theoretical rather than emotional engagement, remain numbingly constant.

“I notice that lots of younger artists are at ease making very abstract work,” he says. “With my generation, it’s different. We were taught by great 80s artists, who focused on performance, conceptual practices, minimalism. Abstract expressionism was not cool. Anything autobiographical was definitely off the agenda. We wound up coming out of art school with this desire to make something sincere, this need to make work with meaning, yet with the theory still guiltily echoing in our heads.”

In his scale and ambition, Ruby appears to be a quintessentially American artist, but he was born in Bitburg, Germany, in 1972 to a Dutch mother and American father. When the family relocated to a farm in Pennsylvania he took up sewing. While his friends were at football practice, 13-year-old Sterling would sit at his mother’s machine, making early versions of the cut-up-and-collage fabric pieces that have become a signature of his work. From early on, the urge to craft and create was coupled with a desire to deface and destroy.

What he calls this “dichotomous relationship to material” is rooted in his adolescence as “a problematic kid who absolutely hated where I lived, which was this macho community in the middle of nowhere”. He came to an agreement with his liberal parents that he could go to gigs in Washington DCas long as he got back in time to get up for school the next day. “I caught the whole DC punk scene. I saw Bad Brains and Black Flag. I think that’s where I began to understood that clothes could be an attitude, whether it was the local hunters in their camouflage and bright orange safety stripes or Henry Rollins on stage in just his gym shorts.”

He also attended local art classes where the option was “creating designs for farming tools or calligraphy – I remember we designed a lot of wedding invitations”. He somehow made it into art college in Chicago and later moved to California to study at the Art Centre in Pasadena, before becoming a teaching assistant to the conceptual artist, Mike Kelly. “Now, that was a rigorous education,” he says, laughing. “There was nothing you could bring to the table that Mike didn’t already know about and have a strong critical opinion on.”

Ruby, then, is nothing if not the sum of his scattergun, and often contradictory, influences, his work referencing everything from Shaker furniture to gangsta rap. Was there a pivotal moment that set him on his epic journey? “I guess my epiphany was seeing the big Bruce Nauman show on my very first visit to MoMA in 1995,” he says, still sounding excited. “I walked in and saw the performance piece where a guy in a flannel shirt beats a punchbag with an aluminium baseball bat. You have to understand, I had come from a traditional figure-drawing class into this whole other universe. But, I understood it completely, not because of contemporary art, but because of that behaviour. I understood that guy with the baseball bat!”

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.