‘I was pretty whacked out’ … film-maker and artist Harmony Korine Photograph: Sarah Lee for the Guardian

In 1998, five years after his first screenplay Kids was shot by Larry Clark and released to international outrage and acclaim, Harmony Korine spent a year deliberately getting himself punched in the face. He was battered to the ground and stomped on by a succession of strangers – orthodox Jew, black lesbian, Arab taxi driver – in an attempt to provoke and film “every demographic” into beating him up. The project was supposed to be a comic homage to his hero Buster Keaton – the only rule being that Korine wasn’t allowed to throw the first punch. Eventually a London bouncer working the door at Stringfellows snapped Korine’s ankle in two, gave him concussion and got him arrested. The film, Fight Harm, was aborted.

“I was pretty whacked out,”

he admits.

“To get myself to a point where I was making those things, I really had to lose myself. And in the process, I lost myself. Looking at the footage as I was making it, I always thought it was funny but everyone else looked horrified and never laughed. That’s when I kind of paused it.”

Korine recently started digitising the tapes he made when he was 25. Aren’t they painful to watch? “Honestly, I was just trying to make people laugh. I was misguided, but in my heart I felt like Fight Harm would have been one of the greatest movies ever made. I thought it would take on this hilarity, elevate the humour like WC Fields or Rodney Dangerfield,” he explains, right foot tapping. “Now it’s more hilarious that I was that stupid, but it is funny. I go back and forth between the idea of releasing it. We’ll see.”

It must be tiring being culture’s perennial enfant terrible. Korine’s been at it for more than two decades. “I’m fine with it,” he grins. “I want to do extreme damage. I want to be disruptive, I don’t care about the flow and I don’t want to go with it.” Since the lurid, candypop Spring Breakers gave him his first commercial hit in 2013, Korine has been working on a Miami-based revenge movie starring Robert Pattinson and Al Pacino. That’s now paused too. “I had an issue with one of the actors,” he says. “I’ve never had an easy time making movies. It’s always been like warfare.”

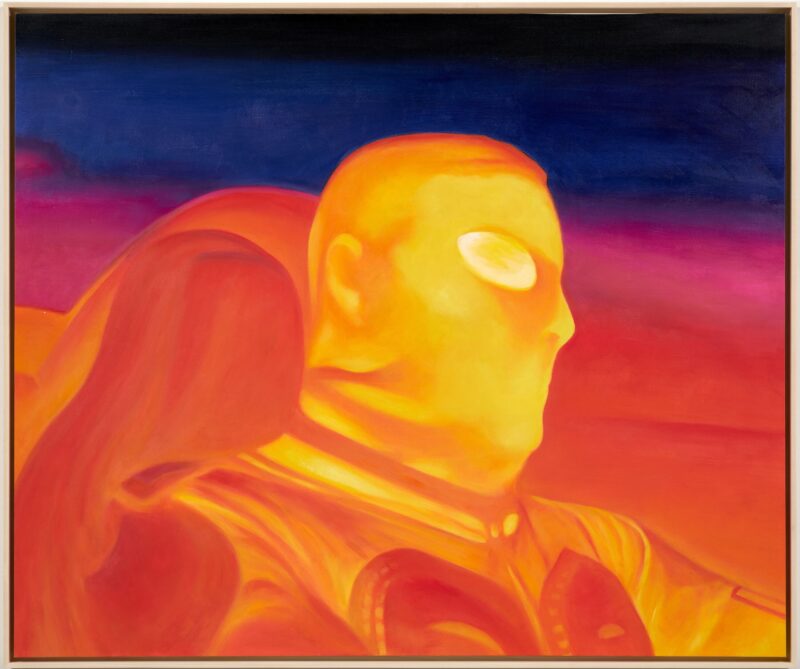

And so for the last few months Korine has been painting in his Nashville warehouse – seven-foot psychedelic orbs on canvases that now stretch along the walls of London’s Gagosian gallery, where we meet. They’re as discombobulating and druggy as anything he’s made – contrived to look and feel like a vibrating high. Korine sits in front of one as we talk. After 10 minutes, I have to switch seats because his head starts pulsating in my eyeline.

“With the artworks there’s a kind of physical elevation and energy. That was what attracted me to drugs. I liked transcending the body, floating, chasing oblivion. It was nuts and, as everyone knows, it takes an extreme toll.”

We chat a bit about crack. Twenty years ago, Korine was in deep with his various addictions and exploding with ideas, firing out his directorial debut Gummo, publishing a novel A Crackup at the Race Riots and directing a second film Julien Donkey-Boy in the course of three years. He and his then-girlfriend and collaborator Chloë Sevigny occupied a bubble of cult cool that defined the decade.

“It was a really exciting time but it was strange. There were a lot of people paying attention and I wasn’t really ready for it and that’s probably when I started getting high all the time.” Sevigny later said that their relationship broke down because of Korine’s drug use. “I don’t really indulge any more,” he says, “because I just liked it so much, it was so much fun.” Presumably in his early 20s, with all that fame and freedom, he could have gone a bit mad?

“I did,” he says, staring at me wide-eyed.

We both laugh to fill the silence. Korine still has a vaguely adolescent snicker.

Two Kids’ cast members, Harold Hunter (Harold) and Justin Pierce (Casper), died drug-related deaths in the early part of the last decade. “I was in New York when Justin died and when Howard died … I was in London.” Korine quietens. “It was fucked up. We were still close friends.”

Eventually, he “stopped doing everything for a couple of years”, and boomeranged through rehab. “I pretty much, like, just disappeared and levelled out.” Korine spent a spell with his parents (who he has described as Trotskyite commune-living Jewish hippies) in the remote Panama jungle where they live, before he moved back to Nashville, where he met his wife Rachel and had a daughter, Lefty Bell.

Did fatherhood change his vision? Korine mugs a comedy retch. “Those kinda questions make me arrgghhh! I mean, in as much as now I have a daughter that I love … but if anything, it’s made me more aggressive.”

Korine might now be a 43-year-old married father, but he sounds pretty much just as he did 20 or so years ago. “I never feel overwhelmed,” he says, when I ask if he ever worries about keeping up with contemporary culture or staying relevant. “I feel underwhelmed. Sometimes there will be this electronic DJ or a kid on a laptop that’s exciting to me. I don’t pay attention to, say, music with instruments that much. I don’t even understand what you would do with a guitar now.”

What does he find interesting?

“Just, like, videos of asses.” He laughs, “girls with huge asses”.

Back in the 90s, Korine would appear on Letterman and prank the show, playing a droll caricature of himself. He was, and still is, a fixture of the style press; his brand of wired, avant garde experimentalism doesn’t really go out of fashion, it just becomes part of the cultural vernacular. American Apparel would not have looked the same way were it not for Kids, while Gummo’s crystal meth aesthetic has been referenced everywhere from the work of Ryan Trecartin to Ryan Gosling’s directorial debut, Mike Kelley’s shorts to Nike ad campaigns.

No doubt, meeting fiftysomething Larry Clark while skating in Washington Square park proved to be the most serendipitous moment of Korine’s career but did he ever feel exploited in those early years? “No! It was great. You have to remember, I was a teenager. I wanted to create things because no one made stuff the way I saw or wanted to see things. The movies I wanted to make didn’t exist for me, I needed for them to live.”

Cineastes, including Gus Van Sant and Werner Herzog, salute Korine as a genuine original ahead of his time, a provocative innovator. Critics and the mainstream public haven’t always been so kind; he has been reviled for being shocking, tasteless, depraved and – most crushingly – boring. The New York Times went so far as to claim that in Gummo, he had made the worst film of the year. Did those reactions ever bother him?

“It affected me more when I was young,” he admits. “When you’re a kid, you’re more emotional. The same openness that allows you to be an artist, makes you susceptible … once I understood that it was a path and I became fortified in my belief, it didn’t matter.” He laughs. “Nothing could stop me.”

At a BFI retrospective the following night, even Korine’s fans seem to find it difficult to know how to relate to him: one young student wants to show him her films, another resentfully accuses him of being a blagger, a third stands up and opens with: “Harmony, I have wanked to all your films …”

Korine is unfazed. He says he wants his films to be as mainstream as possible, played in the shopping malls of America (Larry Clark always said the same of Kids). He tells me about Mitch Poppins, the short film he made in the early 2000s with Chris Cunningham (then Britain’s most wanted music video director), which finally may see the light of day this year: it’s about an American whose Tourettes is so severe that his tic becomes a breakdance. It sounds intriguing, but it doesn’t scream popcorn.

“There are times where I doubt what I’m making,” Korine admits. Chrissie Erpf, Larry Gagosian’s right hand-woman, pops her head in and his slacker punk vibe dissipates for a moment while they blow each other air kisses. “But I don’t have any great fears. It doesn’t really matter to me, whatever the outcome is, is the way it is supposed to be.”

- Harmony Korine’s Fazors is at the Gagosian gallery, London, until 24 March.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.