Gustave Courbet’s The Origin of the World – his clinically voyeuristic 1866 oil painting of a woman shown literally and solely as a sex object, with all distractions, such as her face, ruthlessly removed – hangs in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, opposite his far larger canvas A Burial at Ornans (1849–50).

It is an incredibly powerful juxtaposition, an unforgettable double act. The small, yet white and bright and unavoidably shocking Origin looks across a shadowy space at the huge, dark, funeral scene, with its enigmatic rural faces gathered around the black void of a grave.

If you could ask Courbet what he believed in, this display makes it plain that he would give the same answer as Woody Allen in Sleeper: “Sex and death. Two things that come once in a lifetime, but at least after death you’re not nauseous.”

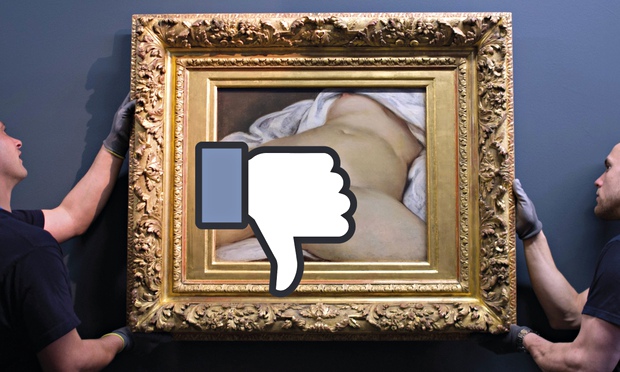

Facebook, it seems, gets nauseous when it looks at The Origin of the World. It has banned Courbet’s 19th-century painting and closed down the Facebook page of French art lover Frédéric Durand-Baïssas for showing it in breach of its nudity policy. Now Durand-Baïssas is suing for damages and demanding the restoration of his Facebook rights.

He is right of course. Courbet is a great artist and The Origin of the World is an extreme, yet perfect embodiment of his passionate and revolutionary beliefs. Courbet wanted to paint raw reality. He sought out the most fundamental human themes because he wanted to escape art’s cosy citadel and make it express life itself. He painted death as it is – an incomprehensible mystery – and mourners with faces so inscrutable you can’t tell if they are grieving or calculating their inheritances. His art shares the dirty realism of the novelists Flaubert and Zola.

Courbet painted naked women in a deliberately unsettling, even kitsch way, to avoid any chance of them being seen in a cosy familiar way as refined sexless “nudes”. In the same year he painted The Origin of the World for a private client he painted Woman with a Parrot to show in the public Salon exhibition. It is a nude that is ludicrously posed, making it all the more carnally real. In Young Ladies on the Banks of the Seine, he portrayed two prostitutes, perhaps lovers, relaxing with one of them showing her underwear. This is sex as the elixir of reality, the secret to making art truly alive.

This revolutionary artist – Courbet really was a revolutionary who took part in the Paris Commune in 1871 – deserves reverence and respect, not the fatuous ignorance behind Facebook’s ban. Suppressing The Origin of the World is as ludicrous as censoring Caravaggio’s Victorious Cupid or erotic frescoes from ancient Pompeii.

On the other hand, the painting is shocking and satisfies most definitions of the word “pornographic”. Maybe even the harshest definitions. The Origin of the World is a violent work of art. Its brutal cropping is aggressive. It has a real sense of evil and madness about it, a David Lynchian evocation of the dark side of sexuality. This was exactly what made it such a cult object for the French avant garde in the 20th century. For a long time, this painting was exchanged as a private exhibit, a shared secret between bohemian connoisseurs who admired its extreme sexual shock.

Jacques Lacan, who bought it in 1955, was married to Sylvia Bataille, who was previously married to the writer Georges Bataille. The name Bataille gets us close to the provocative truth about The Origin of the World. In his pornographic novel, The Story of the Eye this dissident surrealist described murder and torture as arousing – the eye in question is a priest’s that gets gouged out for erotic fun.

Can such a work be literature? Yes, says Bataille in his theoretical writings, and Penguin Modern Classics agrees with him. The daring of the French avant garde, from the 1850s to the 1950s, was to see sex as the stuff of art precisely because it is dangerous and reason-destroying.

Courbet’s extreme masterpiece is at the head of that tradition. It is great art and it is pornography. Got a problem with that, Facebook?

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.