Irresistibly beautiful’: Chiharu Shiota’s The Key in the Hand at the Japanese pavilion. Photograph: Gabriel Bouys/AFP/Getty Images

There is a Rolls-Royce pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale – a gorgeous palazzo on the Grand Canal with a garden full of scented roses. Inside, British artist Isaac Julien is showing his equally fetching views of sparkling glacier caves in outermost Iceland. Visions of diamond-bright ice and cascading blue water flow across five film screens to the brimming-point of saturation, with the figure of the Spirit of Ecstasy cunningly worked into the swirl. These works could double as promos for the country as well as the luxury brand.

Down the canal, however, Julien is putting on a different front altogether in the official Giardini, staging a live reading of Das Kapital in its entirety in the Biennale’s new spoken-word venue, Arena. No doubt he can live with the preposterous contradictions involved. But the double act is emblematic of this 56th edition of the world’s grandest art event, which is nothing if not explicitly critical of capitalism, consumerism and filthy lucre while relying upon them all for its very lifeblood.

The big thematic show in the Italian pavilion, organised by the Biennale’s first African curator, Okwui Enwezor, is full of ladies in Louboutins picking their way nervously through an assault course of videos about global starvation, industrial pollution and the atrocious conditions of garment workers in developing countries. Whole galleries are given over to ecology and the arms trade. Coal sacks dangle like trade union banners from the walls to put us in mind of the decline in mining, and this year’s Golden Lion award goes to the Ghanaian artist El Anatsui for his sumptuous hangings – large enough to cover palazzo facades – made out of flattened bottle tops woven together with fine copper wire; consumption transformed into beauty.

Art can take you anywhere, but this year it is straight into the heart of darkness in many of the national pavilions – the prisons of Brazil, the gay brothels of Chile, the psychiatric hospitals of the former USSR. The predominant media are film and photography, with a preponderance of documents – newspaper cuttings, passport photographs, historic letters and even, in the case of the German pavilion, an entire edition of a Nigerian magazine reporting the recent election, every spread presented in glass cases as if this could possibly pass for art of any sort, let alone actual thought or imagination. You can read all this online.

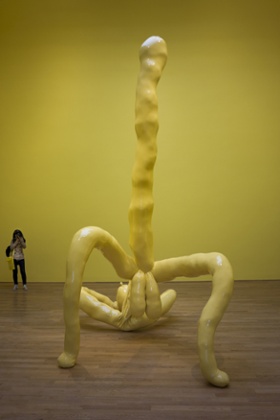

In the British pavilion, Sarah Lucas stands out purely by virtue of having no political content whatsoever (pace the fake tabloid election coverage, as crass as it’s meant to be). Her custard-yellow rooms are full of cast versions of the stuffed-tight porn dollies of the past, reprised this time round as both male and female. She squeezes Dalí’s already much-reprised figure from Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War) in a gigantic yellow sculpture with a balloon-dog head, dangling balls-cum-breasts and something that might be a phallus or a single finger raised to the art world. One in the eye for those saps who buy her lavs, fags and plaster pudenda.

It’s a laboured assault, all this eye-poking rudery, cigs shoved in here and there – the smoking ass, the Monica Lewinsky fanny. You wouldn’t think Lucas, at 52, could still summon the will to turn out these pervy one-liners. Still, we are coming to the end of the YBA revivals at Venice; time for another generation.

Next door’s French pavilion looks a little mimsy at first – empty of everything except a growing tree, and its roots, dug up and prettily installed indoors. But the sound of its rising sap is somehow continuously recorded, making a low and beautiful thrum. And then outside is another tree and another, and as you examine them, trying to discover the source of this inner music, so the trees start to move almost imperceptibly towards you, taking on a life of their own. Birnam Wood come to Dunsinane.

Finland has an enchanted forest by night – silver trees moving against black – that ages through whole centuries in moments on a spectral screen before you. Canada’s comic BGL collective fences a real lonesome pine, scattering rusting cans at the bottom to parody generations of compatriot campers. Australia’s marvellous Fiona Hall finds driftwood on the beach and in her sculptor’s hands turns it into a pageant of lithe creatures, bodied forth like three-dimensional cousins of the prehistoric cave drawings at Lascaux.

Hall’s pavilion is a condensed museum of wondrous objects – warrior masks knitted out of military fatigues; precious weaver-bird nests created out of shredded banknotes; strange new fish fashioned out of the unscrolled lids of sardine cans. Time ticks both forwards and backwards in her fantastical imagination: art makes the future look ancient.

While Julien’s actors are reciting Marx in the Arena space to an audience of practically no one, Hall is one of the few artists here to respond to the real and urgent political present instead of simply rehearsing the usual art-scene rhetoric. A map of the southern Mediterranean is strewn with tenderly formed figures representing the migrants who drowned between Africa and Italy last week; a miniature requiem.

But in general there is a flatness to the Giardiani this year. The American art crowd haven’t come because the timing conflicts with the Frieze art fair in New York, so there was no buzz over Joan Jonas’s US pavilion, in which children appear as naiads and dryads in double-exposure films of a certain dreamy gentleness. And there isn’t very much else to look at otherwise. So many of the pavilions feel like Commonwealth Institute lectures that the clear winner, by general consent, is the irresistibly beautiful installation of exquisite red nets in the Japanese pavilion, through which thousands of keys from all over the world cascade – some caught, others lost; a simple but concise meditation on memory.

It all powers up a little more in the Arsenale, which opens fittingly with an arsenal of weapons – chainsaws, cannons, fierce blades gathered into sheaves and titled Nymphéas by the Algerian artist Adel Abdemessed for their startlingly sinister resemblance to waterlilies. A wall devoted to the African American Melvin Edwards assembles many of his curious fetishes soldered out of cast iron hardware, manacles and hammerheads – a potent row of heavy metal knuckleheads – and Okwui Enwezor, purposefully featuring as many black artists as he can, includes strong mini-retrospectives by Ellen Gallagher, Lorna Simpson, Kerry James Marshall and Chris Ofili.

Wandering through this mile of art, you learn about the pioneering feminists of the Swedish glove-makers’ union in 1898 and the history of the US airforce pilot who fell to earth in communist Albania. The artists of Georgia make you walk across shattered glass to understand what it’s like to live there now. The artists of Tuvalu make you walk across fragile bridges through which water seeps at every step – not so much alluding to the rising tides that threaten that tiny island as recreating them with a certain literal exactness.

And this is the odd thing about the latest Biennale. Most years, one would shy away from the question of what kind of art the world is making now for fear of running into absurd generalisations based on 90 pavilions (88 now that Kenya has pulled out over the very high ratio of Chinese to Kenyan artists selected by Italian curators, and Costa Rica has quit after the curators tried to charge its artists €5,000 to appear in Venice). But this time certain characteristics emerge.

These artists are worried about the state of the world, and their own nations, and many of them don’t care if what they produce is on the level of agitprop. If I saw one endangered plant species I saw 10; if I saw one symbolic skull I saw 20, and I lost count of the number of cankered trees and felled buildings. The vocabulary of Biennale art is diminishing. There are trashed flags and ticking clocks everywhere, along with a whole variety of shop installations – capitalism in microcosm. Which is slightly farcical, since so many of the pavilions have become shops themselves now, the shows paid for by the artists’ galleries and all of the work up for sale.

Of course there are exceptions, not least among the many collateral events such as Catalan sculptor Jaume Plensa’s monumental fine-mesh head appearing in the dusk of San Giorgio Maggiore like a disembodied soul; and a fine show of Peter Doig’s latest paintings, full of jauntily piratical lions and strange new characters to add to his mythological dramatis personae, at the Palazzetto Tito.

But I can’t recall a Biennale with so little visual power, originality, wit or bravado. It feels more like a glum trudge than the usual exhilarating adventure. Art worlders mutter that the soul has gone out of the event as the money pours in, and certain pavilions seem exemplary in this respect. Azerbaijan, for instance, has not one but two, paid for by super-rich plutocrats whose oil wells have not yet run dry. One of them, small and sidelined, contains work by local artists; the other is an ostentatious affair on the Grand Canal stuffed with big names, including the mandatory Warhol – not so much a pavilion as a display of bluechip investments.

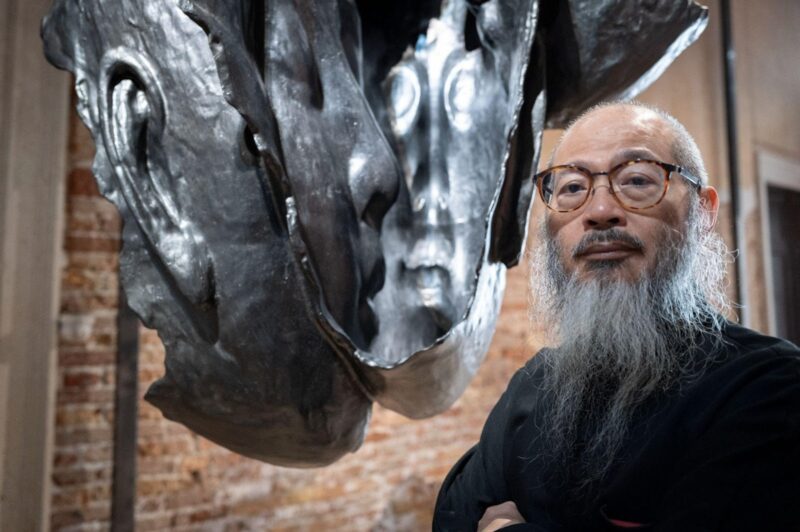

At the very end of the Arsenale, their tails rippling in the marine breeze of the docks, are two colossal dragon-like creatures hovering above the water. They are the work of Xu Bing, a Chinese artist hired to make a sculpture for the World Financial Centre in Beijing. Appalled by the primitive conditions of the migrant workers, he used the worn-out tools of their trade – pliers, shovels, jackhammers – to commemorate their labour and make something magnificent from the debris. These creatures are unarguably symbolic, and so, perhaps, is their positioning as a coda to the whole show: a pair of phoenixes rising from the ashes.

Venice 2015: the 5 best pavilions

Russia A black helmet the size of a room confronts visitors to Irina Nakhova’s haunting pavilion. Sinister and funereal, this surrogate head appears both blind and dead until it suddenly blinks into life and the artist’s own eyes appear trapped inside on a film-screen. The political history of this piece is complex – the artist was one of the suppressed Moscow conceptualists – but its impact is devastatingly direct. At 60, Nakhova is the first woman to represent Russia.

Japan This exquisite installation by Chiharu Shiota was the immediate popular hit of the Biennale. Thousands of keys shower down from the ceiling into tangled nets of crimson thread, some slipping through, others caught in wooden boats straight out of Hokusai. An accompanying video of children trying to summon their earliest memories completes the metaphor of this beautifully simple work, with its intensely meditative atmosphere.

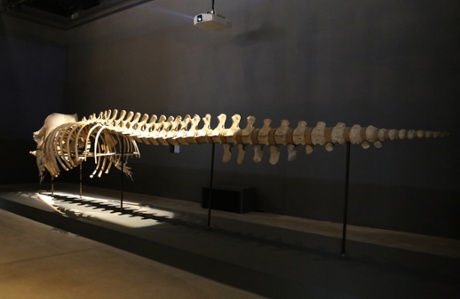

Albania A sperm whale mistaken for a submarine, a mythical mountain and an US airforce plane that fell to earth in 1956, its bewildered pilot forced to apologise for spying, the craft itself installed on the roof of a medieval castle in Enver Hoxha’s birthplace: just a few of the interwoven elements of Armando Lulaj’s terrific tragicomedy of cold war Albania told in sculptures, videos and original film footage.

United States At 79, Joan Jonas is the veteran star of the Biennale and her multimedia installation is both eerie and elegiac. Children appear on double-exposed screens as the spectral spirits of beehives, forests and rivers while disembodied voices attempt to describe ghostly phenomena seen in nature. Mirrors and windows draw the real Giardini into the plot of what becomes a peculiarly poetic visual narrative.

Australia Fiona Hall’s wunderkammer of glimmering objects in the brand new Australian pavilion, opened by Cate Blanchett, shows her extraordinary gift for juxtaposing ideas and materials – guns made out of bread, watercolours out of banknotes, a bestiary of imaginary critters woven from the grasses where they might live. Real insects weave cocoons around miniature monuments and mythical beasts emerge from the relics of the past in this futuristic natural history museum.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.