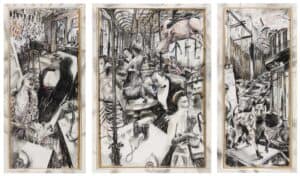

Allen Jones installation view at the Royal Academy

Allen Jones always seems to generate broadly the same debate: is he an objectionable sexist, or an important artist whose overall achievements have been undervalued due to a mistaken interpretation of a small minority of his work?

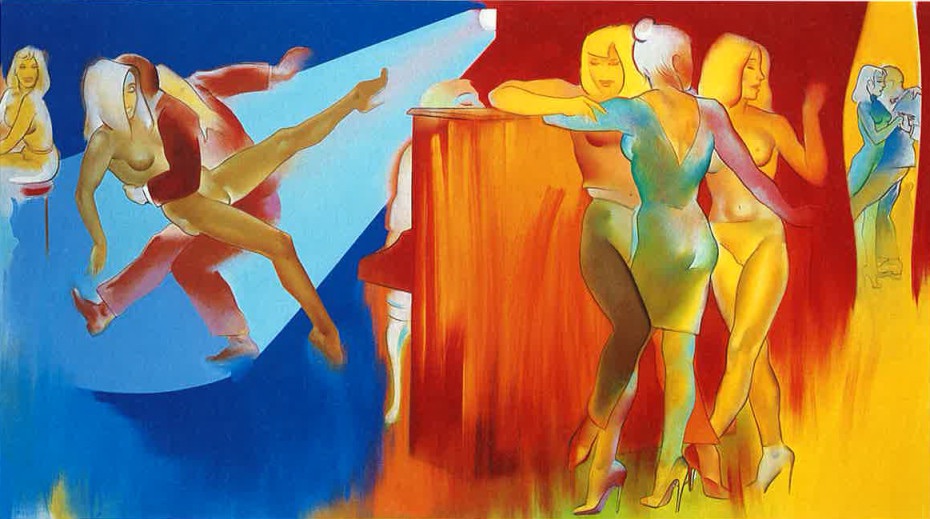

I would argue for a third position on the basis of his current Royal Academy retrospective. Good art needs to marry form and content successfully. Jones experiments with admirable energy, and the bulk of his painting and sculpture deals in potentially interesting ideas about the flux between sexual roles, such as through merging couples; and the analogies to be drawn between various types of performers – in magic, fashion, music, dance – and the artist. That, as a totality, could yield a complex self-portrait. Yet I find Jones’ painterly style of pop falls rather flat,and its self-conscious presentation as art gets in the way of suspending disbelief. Likewise, the cut-out sculptures don’t carry off the necessary grace, and they too suffer from surface distractions. The mannequins, in which women appear to be objectified to the extent that they may be used as furniture, treat the surface as fetish finish and generate a language which delivers their definite punch. But, whether or not they’re sexist – and Jones might point to their uxorious origins as well as a desire to explore boundaries – they fail to address the potentially interesting content of his broader work. Jones, then, succeeds in form and content… but not at the same time.

Allen Jones: The Dance Academy, 2002

Most days art critic Paul Carey-Kent spends hours on the train, traveling between his home in Southampton and his day job in London. Could he, we asked, jot down whatever came into his head?