Felicia Browne was the first artist to die in the Spanish civil war. She was also the first and only British woman to fight for the Republican cause. Volunteering in July 1936, she had just enough time to draw some stunning images of her fellow fighters before being shot by fascists as she tried to save a comrade five weeks later. The crossfire was so intense her body had to be abandoned on the field.

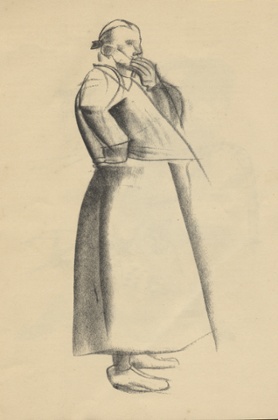

Browne is an artist lost to history. She died at 32, her paintings and stone carvings are virtually unknown, and only a few of her sketches made it back from the frontline. But they are here, now, in this extraordinarily important show at Pallant House – incisive vignettes of men and women in berets and headscarves, watchful and weary, waiting in the no-man’s-land of the open countryside, and the pale sketchbook page, held firm in the contours of Browne’s strong and unsentimental drawing.

This is the first exhibition ever devoted to the involvement of British artists in the Spanish civil war. Stephen Spender – who was there, along with WH Auden, David Gascoyne, George Barker and the beautiful John Cornford, killed in action at 21 – called it the poets’ war, and it has always been more closely associated with writers. But artists fought, reported, campaigned and mourned the bloodshed too, and their images had a striking and immediate intimacy.

Browne shows “the enormous cubic woman” who cooked mountains of food at the filthy barricades where the artist was billeted along with a carload of anarchists. Hubert Finney paints the likeness of a Spanish political prisoner, exhausted, hollow-eyed, heartbroken, his clothes scarcely buttoned, his expression dazed. The watercolour is perfectly matched to the man: as frail and vulnerable as the fading face.

Clive Branson, Browne’s contemporary from the Slade school of art, made portraits of his fellow members of the International Brigade fighting against the fascists, and then later interned in a Francoist concentration camp outside Burgos. Here they are, commemorated with the stub of a pencil: a parade of hungry volunteers from Sheffield, Birmingham, London and the Rhondda, sometimes shirtless, often ill, but always wearing their brigade badges or caps. Branson survived the Spanish camps only to die in Burma in the second world war.

The real caps are also on display at Pallant House along with many other relics: scarlet banners exquisitely embroidered by British women for the volunteers in Spain; hand-carved ambulance plaques sent by the workers of Battersea to their Spanish comrades, now riddled with bullet holes. This is a history of the war in objects as well as images. One of the most potent exhibits is a superbly sinister mask of Neville Chamberlain made by the British surrealist FE McWilliam. Chamberlain was against involvement, and would pledge no money to support the victims on either side. Roland Penrose and three fellow surrealists wore Chamberlain masks, top hats and tails during a May Day protest in 1938, marching through Hyde Park performing fascist salutes in front of a wheeled cage containing a skeleton. If only we had such art groups in modern times.

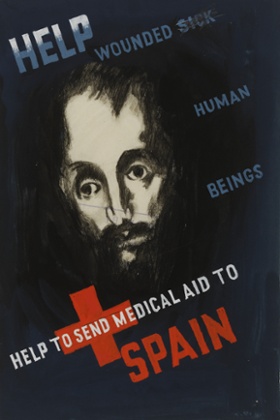

It is well known that Penrose organised the display of Picasso’s Guernica in London that same year; it also toured to Liverpool, Manchester and Leeds, and one senses the influence of this tragic masterpiece developing through this show in many pungent oil paintings of barrages and shattered bodies. Indeed there is general homage to the art of Spain, from the dark and knotted etchings of Henry Rayner, renewing Goya’s Disasters of War for the 20th century – “No Peace”, “No Shelter” cry the captions – to Edward McKnight Kauffer’s poster emblazoned with the haunting face of El Greco as a sort of Spanish everyman. “Help Wounded Human Beings”, urges the banner: a timeless and unimpeachable exhortation.

Kauffer was trying to raise money for medical aid. Many of the strongest works here are graphic campaigns for the diverse groups supporting Spain. For the non-partisan General Relief Fund, the catholic painter Frank Brangwyn produced a monumental litho of Mother Spain in the dead of night, children hanging from her skirts in fear; an imperilled Virgin Mary. For the Basque Children’s Committee, run by a Conservative MP, the architect Anne Acland produced a strong Soviet-style montage of fighter planes and orphaned children.

Some of these children were eventually brought to England, against Chamberlain’s wishes, and cared for by church groups, trade unionists and local volunteers in camps around the country. Grave and beautiful photographs by the communist Edith Tudor-Hart show them in Hampshire, like Bert Hardy’s Glaswegian urchins but raising the anti-fascist fist.

The show itself is remarkably non-partisan. One section is devoted to fence-sitting artists – there is a surprisingly abrupt sculpture of an arm in full salute by FE McWilliam, the fist not fully clenched because McWilliam was, he said, only a fellow traveller – and another to those who were more in favour of Franco’s nationalists, including Wyndham Lewis whose Surrender of Barcelona reprises Velázquez’s Surrender of Breda in vigorous vorticist style, interpolating violence, hangings and death.

But far subtler, and by some way the discovery (or rediscovery) of the show, are the pale and chalky visions of the painter John Armstrong in which violence – in the form of windswept pages – blows down the empty streets of Spain, taking on the spectral shapes of what might be corpses, bodies wrapped around lamp-posts and, in the high blue sky above, a fluttering bird; the elusive dove of peace. His allegories survive their moment: they could stand for all wars throughout time.

This show, meticulously researched and curated by Simon Martin on a slender budget, is exactly what a major museum such as Tate Britain ought to put on instead of one of its bloated surveys of period stars – Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth – whose reputations scarcely need further enlargement. It is rousing, revelatory and poignant: a fragment of British art and political life brought back from oblivion.

Conscience and Conflict is at Pallant House Gallery, Chichester until 15 February

For Guardian &xtra members’ offer click here

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.