The career of Sigmar Polke is the restless search for the optimum means of expressing the truth of the static past in the fluid present. It is the courageous indictment of a tendency to negate catastrophe with a simple alibi which only denies having seen anything at all. Polke deconstructed his sensuous now in order to get to the bottom of a national conundrum that remained locked, and the Tate Modern retrospective currently on show reveals that his key was nothing more or less than the unstable boundaries of art.

Polke is from a generation of German artists, which includes Kiefer and Baselitz, who took it upon themselves to make sense of a past that many would like to have buried without a trace. Unlike the others, who mine philosophy or even art history, Polke turned to popular culture: as the 60s were exploding throughout Europe and North America, Polke saw in the glimmer flashing across West Germany that a new way of making art was in fact a new way of characterising being human in the 20th Century. The implicit intellectual tradition here is as if Heidegger had transmuted being-in-the-world into Hollywood and consumer goods.

Polke’s early explorations of Capitalist Realism deal with the isolation of a divided Germany from a world that was trying move on from a catastrophe, from the point of view of his native land which, by contrast, was paralysed by it. There is none of the heavy, poetic pathos of Kiefer here, but nor is there the gleeful celebration of late capitalism found in Warhol. Instead, there is only the stark realisation that all around the world is changing, globalisation is occurring and everybody still thinks it is the most wonderful idea, but Polke sees it as an infinitely textured Otherness that he can smell but not quite touch.

Works like Socks (1963) and Chocolate Painting (1964) have the sleek surface of pop art, but lack the decadence and frivolity; from West Germany, Polke’s echo of pop sounded altogether more serious. The hues are subdued and the objects are floating in abstract space, like they are absurd or tangential to the real problem of modernity. The real problem of modernity is not how to maintain a moral or intellectual veneer of progress in the face of globalisation, but to reconcile tremendous hope with an impossible sadness. Even the portrait of Lee Harvey Oswald, composed of dots, lacks either iconoclasm or demonization. Polke’s 60s was real but utterly inert, as life went on under the shadow of an impossible trauma. It is as if, following Adorno, Polke was searching for the possibility of poetry after Auschwitz and searched for it in a burgeoning consumer culture which promised salvation but delivered only material possessions.

You can feel Polke incessantly clutching at the possibility of expression as he veers confidently between experiments. Capitalism and its promise of a better life is explored through paintings on luxury fabrics whose patterns acquire a neo-classical painterly quality; Orientialism and a subtle critique of European values are explored in the films of his roadtrip to Pakistan and Afghanistan with shocking neutrality; and conceptual art is mocked in Potato House (1967) and paintings of absurd mathematical equations, while the series of self-portraits – Polke as astronaut, Polke as drug – confront the contemporary individual in the mire of history. Here is a crucial difference between Kiefer and Polke: in Kiefer, humanity is a collective abstraction, a suffering, striving mass reminiscent of Nietzsche’s portrayal of Greek Cheerfulness, but in Polke humanity is comprised of individuals who have faces, and minds and lives.

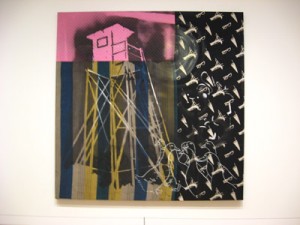

The monumental Watchtower paintings (1984-1986) recall both concentration camps and the Berlin Wall, as if to say nothing changes. But they are steadfastly ambiguous because their pop-like colour and curious playfulness prevents them from being confrontational. Untitled (soot on glass) (1990) stands away from the wall as if there should be something other than a mere shadow behind it, perhaps a metaphor for all history.

Polke stands out because he is both serious and good humoured; he is not weighed down the by gravity of his task like Kiefer, and he does not tell the joke so wryly it is almost lost like Baselitz. There is enough discursive musing and gleeful experimentation here to counterpoint the history and intellectualism that is his subject, and yet sometimes it all swells into a beautiful storm. The triptych, Negative Value (1982), named after stars which are nearly impossible to tell apart, explores ideas of poison and corruption through the alchemy of painting. Something dark emerges out of sweeping, gestural marks of colour, simultaneously as earnest as abstract expressionism and as throwaway as neo-expressionism. And that is only halfway through the show, which takes you on Polke’s journey through the century of screams.

Words: Daniel Barnes