Heavier than our personal belongings themselves is our emotional attachment to them. And what about the social, cultural and political meanings that they also carry? A work titled, Gesamtbesitz or Complete Belongings (2002), by artist Florian Slotawa, opens up questions as to what everyday objects truly mean to us. A parked car and a pile of boxes and bubble wrapped objects occupies storage in the centre of the gallery and beside it, projected photographs flip by, showing the neatly arranged contents of the boxes.

This work is being exhibited at the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin as a part of the exhibition, called Everyday Life (24 May – 10 August 2014). The exhibition contains just three works which express a “non-visible dimension” within their production process and also question the notions of home and identity. Paola Pivi shows, Alicudi Project (2001), part of a 1:1 scale enlarged photograph of an island off the north coast of Sicily, which, in the format of a pixelated PVC roll, is draped dramatically through the historic hall of Hamburger Bahnhof. Bojan Šar?evi?’s Die Lieblingskleider die Männer und Frauen während ihrer Arbeit getragen haben or Favourite Clothes Worn While He or She worked, (1999/2000) is a careful display of dirty clothes which have collected the stains of their wearers at work over the course of two weeks. All three works are connected by their interest in the processes of recording, archiving and presenting. Pivi’s act of photography, translates into a small digital file, in which she wishes to capture and reproduce a whole island; Šar?evi?’s display of clothes which not only carry data about their wearer, but document duration and magnitude of work; and finally Slotawa’s wish to liberate himself from his possessions, yet retain a reminder of their form and meaning.

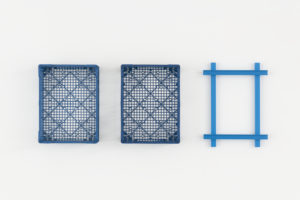

Slotawa photographed the objects in the cardboard boxes to form an inventory. Easing the break with his possessions, he can return to the inventory instead. He therefore carries out a practical task which all artists consciously or unconsciously complete when making work, recording cultural and political moments in time; which includes everyday life. Slotawa began this process of personal recontextualising while he was a student in 1995, when he transferred all his possessions to a studio at the Hamburg Art Academy. They morphed from functioning, singular objects to an architectural installation.

Our need and obsession with collecting objects stems from our hunter gatherer nature, which has transformed completely over centuries of development. Museums and galleries function through collecting, archiving and displaying our historical and cultural identity through objects which take on further meaning once they sit in a glass cabinet. Ivan Šar?evi?’s human subjects choose their favourite garments, which are sacrificed in the name of documentation and display. Florian Slotawa commences the ultimate detachment by departing with his possessions and exhibiting them as artwork, yet at the same time he also performs an act of (self) preservation, contributing his possessions into an archive to be stored safely forever. A keen gallery attendant stops me from moving too close to the boxes while behind the scenes, a security guard watches over the CCTV.