Virgile Ittah in her studio shot by Aaron Hammond

Over the last couple of weeks FAD has been featuring interviews and Q & A’s with the shortlisted artists from the prestigious Catlin Art Prize 2014 up sixth is Virgile Ittah from Royal College of Art interviewed by Harriet Thorpe.

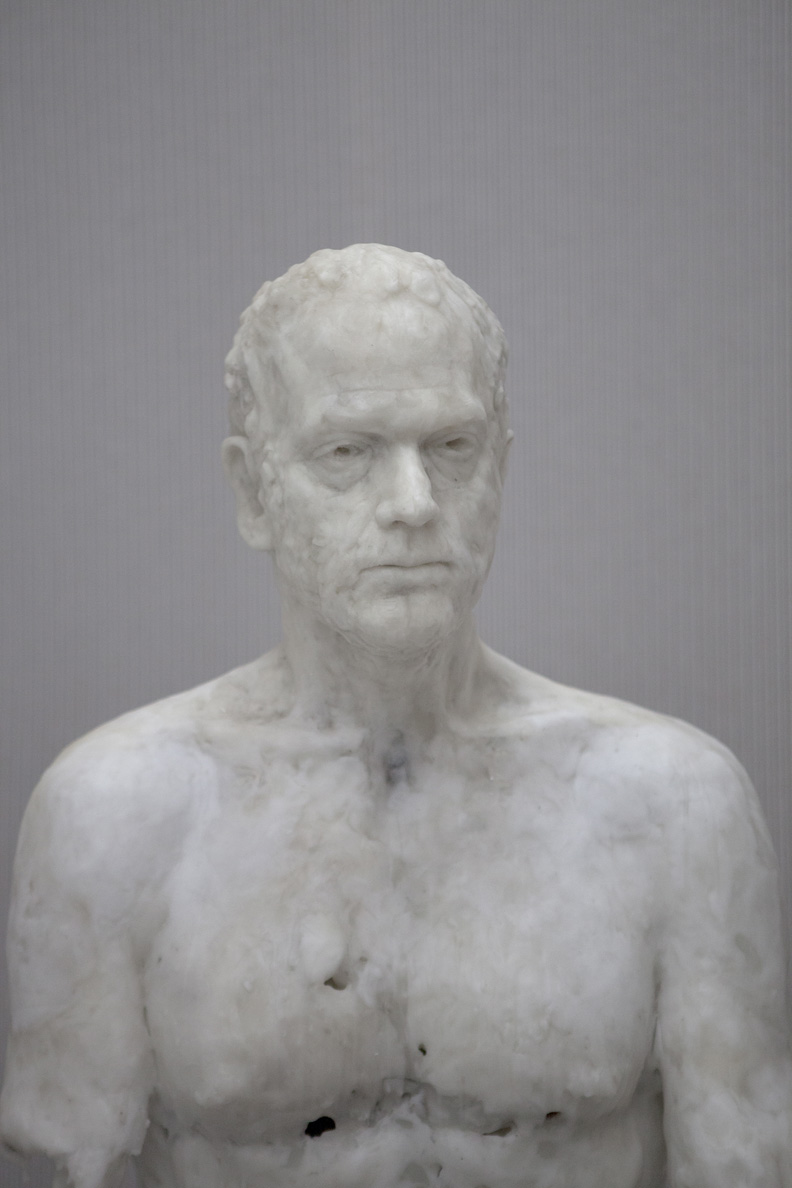

Virgile Ittah is a French artist based in London. Her figurative sculpture and installations made of wax question the human condition and tread a fine line along the trajectories of life and death. Ittah’s work has been exhibited recently in the New Order II exhibition at the Saatchi Gallery. I met Ittah at her studio to talk about her work in progress for the Catlin art prize 2014.

HT: Can you describe the piece that you are working on for the Catlin art prize?

VI: It’s a French title, Echoué au seuil de la raison, and we decided to put the translation in English, Failed/aground at the threshold of the reason. I have been working on it for 4 months, but it’s been developing in my head for 10 months which is how long I’ve been thinking about it. It usually takes me between two and four months to make a work. It will be a full installation, 50 metres square and covered in wax from ceiling to floor. People will be walking on it and the wax will link the floor to the foot of the figure. It sounds completely crazy! It’s so important to have a good technician. Catlin funded 75% of the work, otherwise it wouldn’t have been possible. I’m really thankful to them. When you’re an artist, you do things that you’re not aware of because otherwise, it would be crazy, for instance covering the room with 50 square metres of wax, I try not to think about it too much!

HT: It’s interesting to see the sculpture in it’s unfinished state, because I can see the metal structure within.VI: In every sculpture at some point you can see the metal structure coming through. It’s a kind of skeleton.

My work is a confrontation of the duality between the very organic material of wax which is warm and close to flesh, and then the antique furniture or metal structure which is very rigid and cold. For this one, I used copper, which I don’t usually use. The sculpture includes copper, stainless steel and then the antique Victorian hospital bed, in cast iron. I always do a lot of research about the furniture to find the piece I want. This one is a chapel chair. I bought a pair and the other one is in the Saatchi gallery at the moment. I really obsessed with the “double” and it’s much more difficult to find a pair. I usually find them on the internet. There is a specialist in chapel church furniture and a specialist in antique cast iron beds! Because I order them online, its always a surprise when they arrive, its different to how you expect and the feeling that you have. At the beginning I have an image in my head, a lot of artists make drawings, but I work in my head for a few months and when I’m ready I do some research. I have a blurry idea of what I want, then when the furniture comes I adapt myself to the reality. Making sculpture, the reality always comes back, so failure is constant.

HT: How do you develop the form of the figure?

VI: Sometimes it is a model who poses and I work a lot from photos, so I can take distance from the model and put my own emotion and soul into the work. For this one, I was the model. I asked my partner to photograph me and I worked from the nude photograph which is quite something for me because I’m really shy and I’m not obsessed with self portrait, I’m just at that stage in my practice. Even if it’s not me as a model, it’s a psychological portrait of me. Apart from the work, For man would remember each murmur, it was a lot about the relationship with me and my father. What is really important for me is to not say too much about the work. I try to provoke emotion from people and to touch their soul. I’m always surprised because people reflect their own past onto the work. For some it was dealing with a grandmother dying or a sister full of drugs, I think when a work is good, it can touch anybody.

HT: What are your artistic influences?

VI: For the technique and how to sculpt movement, I’m really deeply influenced by Rodin. Like Rodin, I use no cast and no mould, its only modelling. I add bit by bit, I don’t try to make sculpture, I try to make life. It’s hard to see how the figure can become an abstract form and an alteration of the body, I’m really working on this. I get inspiration from Mark Mendes and Berlinde de Bruyckere, sculptors who alter the human form, but I create my own identity, so I really have to look into my soul. For contemporary artists I’m really influenced by Berlinde de Bruyckere, Michael Borremans and also artists who make installation like Doris Salcedo and James Turrell.

My work, is not only about the figure, it’s the installation built from it. I want the public to experience the work and be part of the work, rather than to see the sculpture as an object with distance, which is really in the past now. To bring something new, we really have to include the viewer in the work, yet not to make it too much of an entertainment, because then its not art anymore. In the new work, for instance, the floor is going to be made fully of white wax, so the floor will become dirtier day after day by the shoes of the public, progressively creating a path with the viewer. With the last installation piece, I wanted to really create a space that was “in between”, hidden, but at the same time the public can go there if they want to. The woman is sitting on an industrial stool, and in front of her is the same stool, but empty so people can sit to be at her level if they want to. I have received messages from the public, people who have been there and really enjoyed it because they had such an interaction with the work.

HT: So what about your personal influences?

VI: There is a philosophical and psychological background to the work that I take from myself. It’s this duality of the “body” which is physical, and the “being” which is immaterial; how you deal with it and where the boundary is between the two. I’m Jewish but I was born in France, so there is this duality of identities. In France it’s not as integrated as England. The system is based on assimilation, so you really have to erase your own origin to become French. It’s a lot about how coming from another country you have to assimilate and erase your background. The work talks about this desire to become French and white but to never be able to do that because of your physical shape.

HT: Are your figures dead? Or, what state are they in?

VI: For me, it’s just before death. The figure in itself is just a visual expression of a feeling. So it’s not the human being that’s important, it’s the feeling that’s passing through it. I think an artist often tries to express something and never succeeds, that’s why they keep going. I did a lot of research about the documentation of the “hysterical woman”. They have this expression… I had it in my head and I asked my partner to photograph me with the same expression. I looked at a photograph of my grandmother who died in Morocco in the 40s. I’ve never met her, but she had exactly the same expression. For me, my family history starts with the death of my grandmother because after that my father was sent to France alone.

The title of the work is a response to the “hysterical woman”. At the end of the Victorian era, women’s freedom had been given, but the status of women was still the same. There was a desire to be free and to evolve, but society didn’t want to give that to them so it provoked a lot of reaction. My work talks about the consequences of this and the constant psychological wondering.

It can easily become dark and depressed, but I try not to make it creepy! I am often surprised by the public reaction because they don’t think its creepy at all. A lot of children like the work; maybe because they don’t have this history of image, they don’t refer it to death, for them its something different. I often have people crying when they see my work, because with the human form you can react much deeper and easily.

HT: Can you talk a bit about why you work with the material of wax?

VI: I trained myself in making the figure with clay, because its how you learn and its easier, but one day in one of the courses we used black wax and I completely fell in love with the material. What I use is a mix of micro-crystalline wax and paraffin which is usually only used in bio-chemistry. The temperature of fusion is much higher at 65 degrees. It took me three years of research to work out how to work with it. Wax was used historically in the Middle Ages when the King died in France. The King has to be mourned for one month, but it was not the real corpse that was being mourned, the French people would pray to the wax copy, which was taking the place of the living human being.

HT: Can you explain the technique you use to create the figures?

VI: Here you can see, the head is finished, but the body is still in progression. You can really see a difference of transparency and colour. I heat and mix the wax and marble dust in the pot, so it becomes liquid at 65 – 70 degrees. I wait for it to cool then shape the work with metal tools. When I think the shape is good, I pour on white spirit, which makes the wax softer and gives transparency. It also will fold down progressively in a few months because of gravity and then the white spirit will evaporate and become harder and more yellow. I don’t have complete control of it, they have their own life. I work from biological drawings and I have a skeleton as well. The anatomy is really important and I really build from the inside. I build the bones, then the muscle for the shape. Even for the face it’s really important, if you want a good anatomical head you need to build from the inside first.

HT: Is it fragile when it’s finished?

VI: No, no, the micro crystalline is sticky and flexible and the paraffin wax is really hard. The high temperature of fusion means that even if you put it under the sun, its not going to melt. There is also the metal skeleton inside that gives it strength.

HT: So it really takes on different properties. Is the colour important to you?

The fake symbol of purity is important for me. The sculptures from the Greek and Roman cultures were not white at all, they were coloured, these really flashy colour that have been recreated by computers. In the Victorian times, they erased and brushed the colour to get this whiteness. It’s this fake whiteness. In the Venice ghetto, when the Jewish people arrived they built a Synagogue, but the Venetian people considered marble too pure for the Jews, so they made this fake marble called Marmorino. My work uses this fake marble effect, it is made of wax with marble dust, so from far away you think its marble and when you get closer its not. I fell in love with the material because I always wanted to create life and a human being, not a sculpture, that’s why I’m not working with clay or bronze.

One of my big inspirations is paintings in churches. When I was little, my mother would bring me to museums and church to see religious painting. In the Jewish religion image is forbidden, which is interesting because others who grew up here all have a strong visual background, but you don’t as a Jew, so I cannot refer myself. In France and Italy it’s Catholic, there are nude people everywhere! The Pieta of Michelangelo in white marble really struck me, it was amazing and so alive, you could feel the veins. It’s a tool of communication, and sculpture was a big force of Christianity in order to convert people; they were not able to read so they were communicating through the image. And image is really powerful. In my work the figure is inspired by the image of Jesus coming down from the cross and maybe that’s why it’s serious and dramatic; I grew up with this image of passion and death.

HT: How important is it for you to communicate a message through your work?

VI: Before sculpting, I was a painter then a photographer. I made this photographic series about illegal workers from Paris and Burma. It was important that they were illegal workers, rather than immigrants, because illegal workers are in a constant state of floating and wandering which was an unconscious interest as a reflection of my own identity as a Jew. I had illegal workers posing for the first sculpture I made. When I was at the RA, I had a really good tutor, Jack Tan, and he said; there is no meaning that it’s an illegal worker, you can make any human being and it would be the same. I realised that an artist doesn’t have to be a politician – its good to have a political message but it cannot be the first plan. France is different from England. There, we are really engaging in political and religious discussion and it’s something we do everyday. Here, I realised quickly that you cannot talk about these things: I tried at the beginning and I found people were uncomfortable. There’s a kind of diplomacy which comes first, but in France we are more straightforward and don’t care to break a friendship over a political subject. In France there is a lot of racism, this is one of the problems and everybody is involved in politics. I think its still difficult to be Jewish in a Western society, this feeling of being in between. As societies become more mixed, it becomes more of a global issue: we are dealing with this “in between” identity, never feeling in place, but in a totally different form.

Every artist makes work with their background and their soul. I cannot make work without these political issues because it’s what I am, but I want other people to reflect their own issues onto my work. I want to touch the public and I want to feed the soul. For a long time I have asked myself the question, “Why do we make art?” and “How can an artist serve society?”, and I realised that maybe, it’s just to feed the soul which is important sometimes.

Words: Harriet Thorpe

About The Catlin Art Prize

The Catlin Art Prize gives talented young artists who have recently graduated from UK art schools the opportunity to showcase their work professionally and win a significant monetary award towards their future development.

Graduating artists from around the UK are visited and assessed by Art Catlin curator, Justin Hammond, and 40 are invited to feature in The Catlin Guide, an exclusive publication showcasing the most promising new artists in the country.

From the Guide, a small number of artists are selected as finalists for the Prize and are invited to demonstrate their progress by presenting a new body of work at the Catlin Art Prize exhibition, held 12 months on from graduation.

Finalist selection is based on the standard of their work and their potential to make a significant mark in the art world over the course of their early careers.

During the exhibition an independent panel of judges including Turner Prize winner Mark Wallinger will select a winner who will receive the £5,000 prize. A visitor vote is also held, allowing the general public to vote for their favourite artist via the website and at the exhibition. The winner of which will receive £2,000.

From the 2014 Guide seven artists have been invited to demonstrate their progress by presenting a new body of work at the Catlin Art Prize exhibition, held 2nd -24th May 2014 More Details: www.artcatlin.com