Lynn Chadwick The Watchers 1960 Bronze Height 235 cm / (92½ in) Photo: Jonty Wilde, 2013

Lynn Chadwick Crouching Beast II 1990 Welded stainless steel 183 x 213.5 x 472.5 cm / (72 x 84 x 186 in) Photo: Jonty Wilde, 2013

Blain|Southern and Blain|Di Donna will present three simultaneous exhibitions of Lynn Chadwick’s work across London, Berlin and New York this Spring 2014.

This will be the most substantial survey of the artist’s practice ever undertaken. In addition, the Royal Academy of Arts, London, will display a group of large-scale sculptures in its courtyard – Chadwick was elected Senior Royal Academician in 2001.

Chadwick, whose estate is now represented exclusively by Blain|Southern and Blain|Di Donna, was one of the leading sculptors of his generation, and his sculptures feature in the collections of most major museums, including MoMA, New York; Tate Gallery, London and Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. The artist was born in Barnes, London, in 1914 and died at his home Lypiatt Park, Gloucestershire, in 2003 aged 88.

Chadwick is known primarily for his metal works that were often inspired by the human form and the natural world, but which also at times veered close to abstraction. Producing sculptures that were defined through their exploration of form, stance, line, balance and attitude, Chadwick established a new method of working that marked a departure from previously dominant sculptural traditions.

The works will be selected by the exhibition designer Bill Katz, and the three exhibitions will be accompanied by a new, fully illustrated publication on the artist.

About The Artist

2014 marks the centenary year of Lynn Chadwick’s birth. He began his career in the architect Rodney Thomas’ office in London. Following war service in the Fleet Air Arm (1941–44) he moved to Gloucestershire in 1946. His route to sculpture was through exhibition design – work which involved the practice of construction and the juxtaposition of various materials. With the encouragement of Thomas, Chadwick created objects in which linked, balanced forms floated freely in space and were suspended from the ceiling – his first mobiles. Very few of these early mobiles survive, although The Fisheater (1951) is in the collection of Tate Gallery, London. The mobiles were made of balsa wood and cut copper and brass shapes, often fish-like and sometimes coloured, and were incorporated as decorative features in the exhibition stands. Later, he developed ground supports for the mobiles and termed them ‘stabiles’.

In 1949, Chadwick’s first mobile sculpture was shown in the window of Gimpel Fils, London, and his first solo exhibition was held at the same gallery a year later. During this period, he was increasingly concerned with the ground supports of the ‘stabiles’, and these eventually became sculptures without any mobile elements. To realise these, Chadwick had to learn to weld, developing many new techniques through trial and error in order to find an architectural or engineering solution to the construction of mobiles and sculptures.

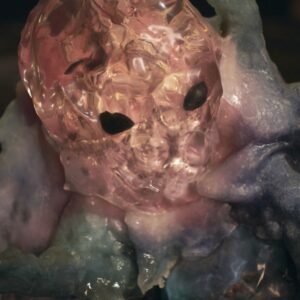

Chadwick developed a technique of taking steel rods and welding them together in space to criss-cross, join and radiate out, which formed three-dimensional shapes (armatures) – akin to the architect’s space frame. This armature was filled with an industrial compound called ‘stolit’ — a mixture of iron fillings and plaster that could be applied wet and, when dry, chased to achieve the surface Chadwick desired. This surface was sometimes textured, sometimes smooth — a skin, as it were — but with the original rods still visible. This external armature is a defining component of Chadwick’s imagery. Chadwick tended not to do a sketch beforehand – the sketches in his workbook came after the work was completed, serving as a record of what he had created.

His work was first presented to an international audience in 1952, when he exhibited at that year’s Venice Biennale alongside a new generation of British sculptors. Four years later, at the 1956 Venice Biennale, Chadwick won the coveted International Prize for Sculpture, prevailing over Alberto Giacometti, and making him the youngest post-war recipient of the prize.

While Chadwick continued to construct his sculptures by the same methods, in 1955 he decided to cast them in the more durable medium of bronze, which also allowed him to expand his practice from unique sculptures into editions. The surface of the casts was then treated to achieve the subtlety of colour that Chadwick was searching for with each theme he was working on – sometimes golden, sometimes grey. Later, he also cast in silver and gold. Of his work, Chadwick would say that he did not have a particular theme in mind, more a ‘problem to solve’ before he was able to move onto something else. Looking back at his whole body of work, it is possible to see the artist’s work developing from the mobiles and ‘stabiles’ in the early 1950s through to the animal forms that in turn evolved into more obviously figurative sculpture.

In the 1960’s, Chadwick became interested in both abstract form and human form – and later, in the detailed observation of how a figure moves and the stances they might take. During the 1970’s and 1980’s he started to standardise these figures. He developed a personal visual ‘code’ – eventually most of the male figures had rectangular heads and the females had triangular heads (or flowing hair as in High Wind).

Chadwick did not analyse his work, leaving interpretation to others. A very private man, he gave few interviews and would rather discuss the formal and practical nature of his sculpture over its meaning. He often spoke of a general feeling that he was merely the craftsman.

In an interview on the BBC Home Service, published in The Listener, 21st October 1954, he said: “It seems to me that art must be the manifestation of some vital force coming from the dark, caught by the imagination and translated by the artist’s ability and skill. Whatever the final shape, the force behind is… indivisible. When we philosophise upon this force, we lose sight of it. The intellect alone is still too clumsy to grasp it.”