Larry Achiampong is a Ghanaian-British artist based in London. In 2008, he graduated with an MA in Sculpture from the Slade School of Fine Art, University College London. He works across media including sculpture, painting, photo collage, performance and sound. Achiampong has exhibited, performed and presented projects both in the United Kingdom and internationally. He has shown work at Tate Britain, Tate Modern, Iniva, the ICA, and Yinka Shonibare’s Guest Project Space. In June this year he presented a new hour-long performance at Tate Modern as part of the Group Show ‘Project Visible’. Achiampong’s experiments with sound (as musical and archival material) led to the production of the vinyl LP Meh Mogya (Sample of Me) in the form of a concept beat tape. His concept beat tapes, which also includes the recent LP More Mogya, overlay a rich variety of sounds and samples that draw on his Ghanaian heritage, his parent’s Highlife record collection and the music culture he grew up with in London. In March this year he was invited by Tom Ravenscroft to present a guest mix on BBC Radio 6 music, which included tracks by his alias Black Ph03nix. Achiampong has also recently produced the mixtape ‘Africa in your Earbuds’ for Okay Africa a hub for African youth culture. For more about the artist and his work see: www.larryachiampong.co.uk.

Interview by Yvette Greslé

What are the ideas and interests that drive your work as an artist?

The work that I’ve produced so far (as an artist) is informed by my background and my heritage. My parents came over to the UK from Ghana in the late 1970s/early 1980s. I was born here in East London, and raised in Bethnal Green. I’m interested in visiting the past, in looking back retrospectively. Whenever I’m asked the question: ‘Where are you from?’ I respond (in an East London accent): ‘From Ghana’. The response is: ‘But your accent doesn’t say that’. I was brought up with the values and customs of a Ghanaian, more specifically of an Ashanti person. I grew up with these but when I was out playing with my friends in East London it was fish and chips, football, that type of thing. I’m interested in the relationship between my Ghanaian heritage and the experiences of growing up in East London in the 1980s and the 1990s. People ask me: ‘Don’t you see yourself as British?’ My response is: ‘I see myself as a Londoner’. I don’t know what British means. I think these ideas inform my work. I like to have discussions about where I come from, and I explore these conversations in my work.

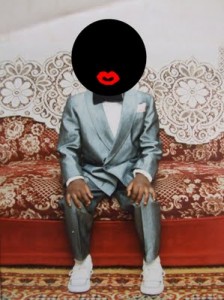

‘Lemme Skool U’. Digital montage on analogue prints, 2007.

‘Lemme Skool U’. Digital montage on analogue prints, 2007.

Where does the Cloud Face come from? It’s a continuous presence in your work so far. Race is an important aspect of your work, and the Cloud Face holds so many derogatory images, stereotypes and prejudices. For example, blackface minstrel shows and vaudeville.

There are many images, thoughts, memories and experiences that inform the Cloud Face. We ate a lot of Robertson’s marmalade as kids. I always found the experience of looking at the Golly character, which was part of their branding, strange. It looked so alien. Why would this kind of image exist? Over the years I put the pieces together. I believe John Robertson (the son of James Robertson who started the Robertson brand) based the Golly character on the black rag dolls he saw children playing with in America. The reason the Robertson’s brand discontinued the character around the early 2000s was not because it was derogatory but because (from a business point of view) they found that it no longer appealed to their fan base. So their reason for getting rid of it was entirely to do with business. It’s not to do with ethics or with what’s right or wrong. A lot of this derogatory stuff is still in the air. It’s there in the art world too. This motivated me to create the Cloud Face.

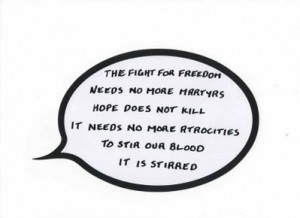

‘Hope does not kill’. Buff proof ink on customised sticker, 2012.

‘Hope does not kill’. Buff proof ink on customised sticker, 2012.

Your work draws a lot from comic culture: the Cloud Face and motifs such as speech bubbles.

I grew up reading a lot of comics and graphic novels, including Vendetta by Alan Moore. It presents a vision of Britain that is dystopian and bleak (a brutal, totalitarian state). It deals with themes of prejudice, race and xenophobia. One of the characters is a guy called V identifiable only by the Guy Fawkes mask he wears. He represents a spirit of rebellion and resistance. You might recognise this mask from the Occupy Movement: the smiling face with the moustache. It comes from this comic. I always found him interesting but could never relate to the Guy Fawkes mask. My own practice is about telling stories through images and themes that I can relate to.

When you talk about race or class in your work it’s something that is deeply embodied and experienced. It’s not just a theoretical abstraction for you.

I studied in an environment where there were no black or working class people apart from me. It was alienating in some ways: studying in a place where people are talking about issues to do with race or class from a very different point of view. I could enter these conversations but I never felt comfortable with them. I felt that the way these conversations took place was very patronising, and people were talking about things that they hadn’t actually experienced.

‘He’s Not (Racist), He Owns a Black Cat’, digital montage, 2012.

‘He’s Not (Racist), He Owns a Black Cat’, digital montage, 2012.

A lot of your work deals with the experience of being a black man. I’ve noticed how in London it’s black men that get stopped by the police most of the time.

Yes. It happens to me. My work is the only place I can talk about these issues (whether it’s a one-liner or whether it explores an event in a very visceral way). ‘He’s Not (Racist). He Owns a Black Cat’ dealt with the John Terry and Anton Ferdinand incident, and the sensationalism attached to racism within football on the pitch, in the stands and amongst the commentators. It’s not a new conversation. It’s been made new by the media. This stuff has always been there. I actually made works years before that explored football culture. You’re dealing with powerful cultural icons. That particular moment dealt with whether there was racism or not. He obviously had been racist. You look at the footage; you look at the evidence and what was covered up. I was interested in what people were trying to cover up.

What do you think the power of art is in entering an event such as this?

I think the artwork allows a moment of focus. I’m not talking about who is winning or losing the premier league. I’m putting a moment under a magnifying glass. That’s what the art does. Art can isolate or focus on a moment in time. I was interested in taking a freeze frame of a moment and exploding it. I’m interested in looking at images from different perspectives. I play with the original image or photograph, and deface it just a little bit. ‘Cloud’, Live performance at Tate Modern, 2013.

‘Cloud’, Live performance at Tate Modern, 2013.

The live performance at Tate Modern (in the Poetry and Dream exhibition space) was interesting from the point of view of inserting a discussion about race into an institutional space.

I wanted to recreate a 2007 photo collage of myself in a suit with the Cloud Face. I was interested in the idea of bringing the Cloud Face into a three dimensional, living, breathing world or environment. Bringing the Cloud Face into the museum was interesting. It was not just about the experience of being black or an artist but also about the experience of going to gallery shows. There are things that are not really spoken about. Why not have a conversation without being literal. It was about bringing up a discussion that just isn’t being had, simply by existing. I sat very still. Like the museum invigilator, the invisible people. I wanted to make things that are invisible, and not spoken about, visible. I couldn’t see through the face. It was very claustrophobic and difficult to breath. It was important that it took place in the Picasso space. I wanted to reclaim a power or energy by existing as the Cloud Face in that space. Picasso claimed the energy of various African arts and traditions. I thought: ‘Why can’t I do that as well?’ I chose not to perform at the entrance to that particular part of Tate: you also had to walk all the way into the space to experience the work. It became a journey.

I would like to take the Cloud Face to other gallery spaces or city streets. What would it mean for the Cloud Face to walk down Liverpool Street or through Mayfair; or through Manhattan or central Tokyo? I thought that the gallery space was a good place to start that conversation. The form of the gallery space is very interesting to me but on the other hand I am very conflicted about it. That’s why I did the ‘Jam in the Dark’ project. ‘The Cut’, Acrylic, emulsion, poster paint, spray paint and marker on wooden hoarding, 2010.

‘The Cut’, Acrylic, emulsion, poster paint, spray paint and marker on wooden hoarding, 2010.

What was the impetus for ‘Jam in the dark’.

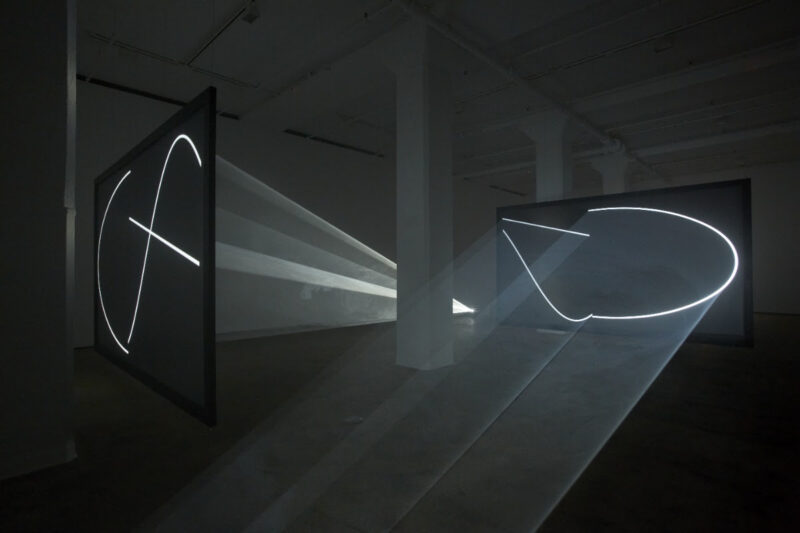

I was thinking about gallery spaces, which I am very conflicted about. Why do we always have galleries that are white walls, and grey floors? What does it mean? What do these spaces say about power and hierarchy? I wanted to flip that on its head. As I do, as the prankster. Let’s turn out the lights. Let’s paint the walls black and make it as dark as possible. You can’t see anyone around you. You don’t know what they look like. You’re creating a moment where people are on an equal footing but through fears and through the senses. Through restricting some senses others are heightened. You can’t see, you’re being restricted, and held back.

It’s an interesting idea because prejudice is so much an aspect of sight and vision. You as a visual artist are denying or obfuscating sight. You also emphasise bodies in a space. The room is dark, and so vision is obscured? There is also music? Musicians are literally jamming in the dark? It is all left to chance? John Cage is perhaps a reference point. Sound is disrupted and dissonant?

Yes. I invited a range of musicians to come into the space to communicate with one another through sound. Everyone, musicians included, was on one level space. There was no stage. I would like to take the ‘Jam in the Dark’ performances into three-dimensional sound, which would entirely fill the space. Then, the viewer, invited into that space, would be entirely engulfed by sound.

You seem to be very interested in the body, and the body’s relationship to music and sound; and to vision.

This relates to my interest in audio samples: how do these embody the lives of individuals through time? For the Meh Mogya project I asked myself the question: ‘How would I be able to hear a portrait, of where I come from, of who I am?’ We use our vision to create ideas about portraits. Very rarely do we do that with sound. For me, sound is something that is under-rated as a way of expressing where it is we come from. I looked through my parent’s record collection, their Highlife collection. The samples for the first part of Meh Mogya came from these records. Records associated with my childhood memories. There are these moments of discovery and re-discovery. I’m isolating sounds, and chopping them up on an audio sampler. I turn these into miniature beats. I’m employing some of the techniques that are used within hip hop, within some disco and electronic music (within popular culture). I take on the element of the loop, of repetition, repeating a moment in time. But even when that moment in time is repeated it can sound different when that loop is re-visited again and again. You also have the context and history of Highlife.

More Mogya can be downloaded from www.larryachiampong.co.uk. You can also listen to tracks on soundcloud. Look for Blackph03nix.

More Mogya can be downloaded from www.larryachiampong.co.uk. You can also listen to tracks on soundcloud. Look for Blackph03nix.

Elaborate on Highlife, its relationship to Ghana.

Highlife is a sound that was developed in Ghana. I focused on Highlife music produced between the 1960s through to the 1980s. This is considered by some to be the golden era of Highlife music. Highlife is not that well documented but it pre-dates jazz. It begins in the early 1900s. Companies like HMV were working with fisherman and sailors from the coast, and would record their sounds. With trade you also had western instruments that were married into traditional sounds. Highlife came from working class people who were talking about various aspects of life but approaching it from a very optimistic point of view. It’s a very happy sound. In a way it’s an antithesis to the blues. It doesn’t focus on sadness. It has a big band sound. Each musician plays a separate sound or rhythm but everything has to lock. When the rhythms are isolated they might sound really simple but when you have five or ten or fifteen it becomes this polyrhythmic assault of sound that just pulls you in.

While I was listening to the sounds from my parents record collection, I also decided to research some of the artists. I came across Professor John Collins, a musicologist based at the University of Ghana in Accra. He’s written on various forms of African music including Highlife. He also established the Bokoor African Popular Music Archives Foundation in Accra. It houses material based on Highlife music and music that connects to it. I got in touch with him about my project: the idea of bringing together the Highlife sounds with contemporary technology and beat making culture.

After I got in touch with him, I turned my bedroom into a production studio. I listened closely to the Highlife sounds. I isolated the loops, recreated them, chopped them up, turned them into beats and put them together one by one. I then sent this to John Collins and we began a conversation.

![Glyth-4-web[1]](https://fadmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/Glyth-4-web1-300x212.jpg) From the ‘Glyth’ series, digital montage on analogue prints, 2013.

From the ‘Glyth’ series, digital montage on analogue prints, 2013.

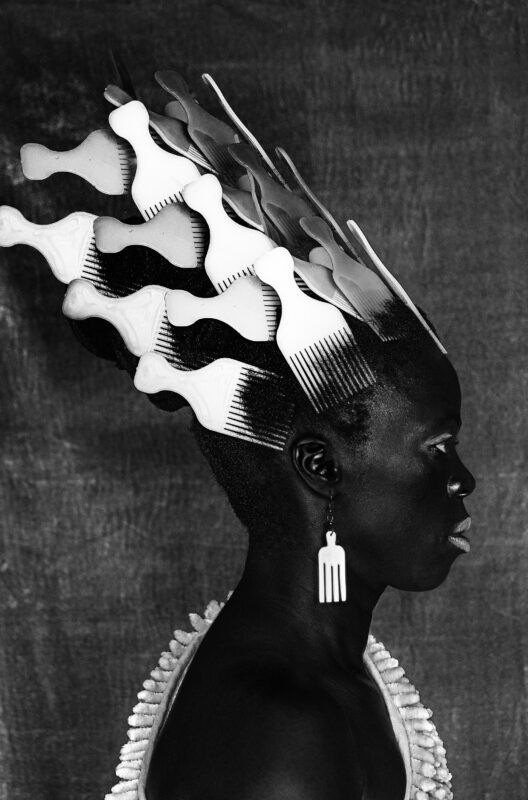

The ‘Glyth’ series is based on personal family photographs? It’s interesting how you re-stage these images, you add the Cloud Face and you work with their imperfections.

My mother would send photographs to family in Ghana with the letters that she wrote. She would very deliberately orchestrate the photographs. It was almost unreal. It was like we were demonstrating products in a catalogue. I like the accidents that happen in family photographs or snapshots: things like shadows. I think you only get these interesting accidents with family portraiture. You try and set everything up as perfectly as possible but there’s always an imperfection. I scan the photographs. I don’t do too much to the image. It’s the process of selecting the image that’s most interesting to me.

Ashanti culture is grounded in so much symbolism and it’s very visual. For example, cloths are not just cloths. The motifs that decorate them symbolise something. They invoke proverbs or they tell you a story about the wearer. Different cultures have different ideas about what an artist is, and what a creative person is.

On the record design for More Mogya I incorporated the symbol Sankofa: a bird with its head turned backwards. It signifies the proverb ‘look back to go forward’. You have to understand where it is you’re coming from before you can create something for the future. This is a very important symbol for me as a man, as a black person, and as an artist.  ‘Golden Stool’, Sese wood, spray paint, 2013.

‘Golden Stool’, Sese wood, spray paint, 2013.

www.larryachiampong.co.uk