Screenshot from ‘The Devil’s Haircut’ (2013), Digital Video projection, 6m 38s.

Screenshot from ‘The Devil’s Haircut’ (2013), Digital Video projection, 6m 38s.

Two short films by Malvern-based artist Stuart Layton are currently on show at Wolverhampton Art Gallery (through to 14 September 2013). The films, ‘The Devils Haircut’ and ‘The Impossibility of Living in the Present’, form part of an as-yet incomplete trilogy titled, ‘You’ll Never Work in this Town Again’. ‘The Devil’s Haircut’ (2013), is about a local barber called Dave who, had he not needed to flee his native Iraq, may have fulfilled his dream of becoming a famous ballet dancer. ‘The Impossibility of Living in the Present’ (2012), offers snapshots of characters and pastimes from local working-class communities torn apart by the political context of the 1970s and 1980s.

Stuart Layton graduated from the University of Worcester in 2012, and is due to begin his MA at the Royal College of Art in September this year. In April 2013, Layton was named a runner-up in the award exhibition New Art West Midlands, and received a bursary to create new work for the exhibition. www.wolverhamptonart.org.uk

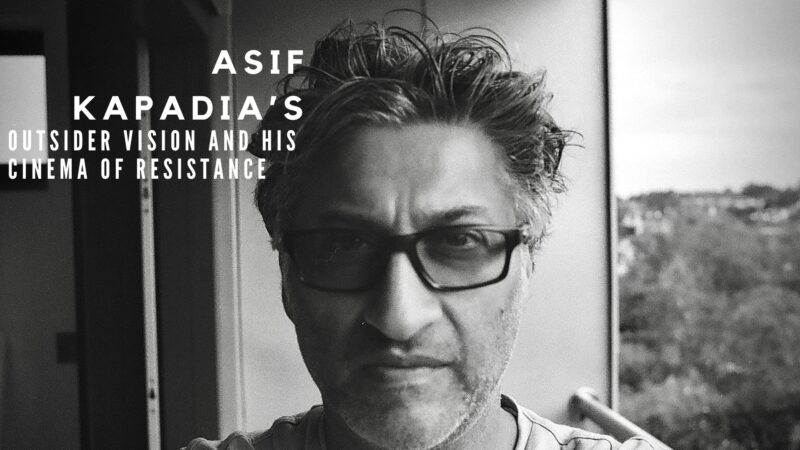

Interview by Yvette Greslé

Watching both the films – ‘The Devil’s Haircut’ and ‘The Impossibility of Living in the Present’ – I was struck by the blueness of ‘The Devil’s Haircut’ and the way you overlay images and effects of light in ‘The Impossibility of Living in the Present’. It’s interesting that you originally saw yourself as a painter.

Yes, I saw myself as a painter, and started messing around with film and video as something to help move stuck paintings forward. I was introduced to the work of Stan Brakhage by a tutor. I was struck by how similar Brakhage’s processes were to that of painting. I was also interested in the links between Brakhage and Abstract Expressionism and in how a filmmaker could be considered the next generation of a movement dominated by painting. Now most of my work tends to be realized within moving image and installation, though I would say a lot of the working out is done via the process of painting.

The layering and use of multiple sources in my videos comes from the desire to make the process of producing video as similar to that of painting as possible. This is why I’m interested in overlaying images, and in leaving visible traces of earlier work. The thing becomes this self-contained document of its own history. The work embodies the process through which it is made.

I coloured the original footage for ‘The Devil’s Haircut’ blue. I wanted it to be sombre, and to create distance between my film and the original footage. Screenshot from ‘The Impossibility of Living in the Present’ (2012), Digital Video, 3m, 39s.

Screenshot from ‘The Impossibility of Living in the Present’ (2012), Digital Video, 3m, 39s.

What was the departure point for ‘The Devil’s Haircut’?

It began with a recollected conversation with my mother, and found material that I had archived for use in another project. In the mid to late ‘90s my mother started getting her hair done at a barbershop in Darlaston. She came home very pleased with her new do and told me how the barber ‘Dave’ was from Iraq. Dave was actually nicknamed ‘The Butcher of Baghdad’ by kids who joked that his haircuts were terrible! While cutting hair Dave told stories about his life back in Baghdad. He said he came from a loving family, his mother was a teacher, his father a doctor. Dave was encouraged to take part in cultural activity and was particularly fond of piano and dance – especially Ballet. The stories Dave told about his life in Iraq countered those I read in the media.

While researching for an unrelated piece of work I began looking for footage of ballet dancers. I came across the footage of the dancers, and was compelled by it. It was mesmerising and poetic. I archived it for future reference. During the Christmas holidays, in 2012, my aunt brought up the Iraqi barber in conversation. I remembered the footage of the ballet dancers, and the work started to come together.

Does your work emerge out of a research process? Do you create an archive while researching for the films?

Yes, I keep an archive of material that I find interesting in some way. This might be video clips taken from the internet or 8mm and 16mm film. I discover the film in charity shops and in my father’s loft. I collect old photographs, song lyrics, lines from books, newspaper headlines, popular culture and I draw on childhood memories. I also shoot my own footage surreptitiously – often from the mundane or domestic or just stuff that catches my attention as I’m walking around. This is added to the archive, which is a kind of depository for future works. Screenshot from ‘The Impossibility of Living in the Present’ (2012).

Screenshot from ‘The Impossibility of Living in the Present’ (2012).

‘The Impossibility of Living in the Present’ appropriates from so many different visual sources. I notice footage that looks like it comes from computer games?

I used footage from several retro computer games. I’ve always been interested in video games and technology in general, and my generation was the first to have these technologies at home. All the clips depict the death of a character losing a virtual life or ‘game over’. So I guess they are an allegory of life really. A reminder that death is the one thing every one of us has in common. Maybe I escaped the present by immersing myself in these virtual worlds.

Dancing comes up again in ‘The Impossibility of Living in the Present’.

The dancing footage was taken at a ‘Northern Soul’ soul night at what used to be my local working men’s club. (Now a co-operative run social club). Northern Soul is a musical movement that emerged in the 60’s within working class communities in the North of England. It spread throughout the country mostly in working class areas and is somewhat of a phenomenon. Although mostly underground – Northern Soul still has an almost fanatical following. Tales of all-nighters are almost akin to folklore in parts of Wolverhampton.

In ‘The Devil’s Haircut’ you use footage of cowboys. What is interesting for you about this figure?

The lone cowboy is so iconic in itself: the All American Hero, larger than life. The loner who rides into a town and solves its problems yet cannot solve his own. He is the hero who can never find peace or happiness, despite bringing it to others. Gordon Cheung’s paintings of cowboys reminded me of my interest in the Westerns. Screenshot from ‘The Devil’s Haircut’ (2013).

Screenshot from ‘The Devil’s Haircut’ (2013).

Where did you source the soundtrack for ‘The Devil’s Haircut’?

I’ve been a fan of Spaghetti Westerns since being introduced to them as a child by my father. Ennio Morricone composed the soundtracks to many of the best ones. These soundtracks, in particular ones from ‘The Good, The Bad & The Ugly’ (1966), ‘A Fistful of Dollars’ (1964) and ‘For A Few Dollars More’ (1967), are really well known. They’ve been sampled in hip hop songs such as ‘Planet Rock’ by Afrika Bambaata. I was very into hip hop culture as a kid growing up in the ’80’s.

The soundtrack I use in ‘The Devils Haircut’ is from the movie ‘For A Few Dollars More’. Rather than just using the theme tune I sampled extracts of dialogue from the movie. The soundtrack is kind of a remixed version of the original. I was thinking about the American invasion of Iraq – the idea of cowboys riding into town to free its people from tyranny (apparently anyway).

Is the classical music soundtrack for ‘The Impossibility of Living in the Present’ also from cinema?

It’s taken from a favourite movie – Martin Scorsese’s ‘Raging Bull’ (1980). A real tour de force of cinema, you feel like you’ve been through the ringer after watching it. It was also the first time that I realised the enormous emotional power that classical music has. Emotion is important to me in any art form. If something evokes an emotional response – whether positive or negative – it tends to stay in your memory a lot longer. The music allowed me to slow the pace of the film, and is a counterpoint to the pacing of the many, layered images. I also like the ironic, poetic feeling of the music together with the clips of Bernard Manning smoking his cigar. Manning was a very famous comedian of the ’70’s & ’80’s who started out playing gigs in working men’s clubs in the North of England. Themes of class come up in my work. It’s ironic because, like many of his contemporaries, Manning was sexist and racist. The shots of him puffing away on stage reminded me – in an odd way – of the fate that awaits De Nero’s character in ‘Raging Bull’ – not a particularly nice man, a bigot, smoking cigars on stage whilst telling jokes. Screenshot from ‘The Impossibility of Living in the Present’ (2012).

Screenshot from ‘The Impossibility of Living in the Present’ (2012).

Are you especially interested in everyday life and people, as opposed to big historical themes?

I try and find interest in the everyday or mundane. If you look hard enough everything is interesting. All of us have stories to tell. We might appear different but if we scratch below the surface we often find that we all share common ground. We have similar worries, views, hopes and dreams despite our background. I think there is a kind of universality to human experience.

Do ideas about narrative and story-telling interest you?

I’m interested in how narratives are open to interpretation, and in how a story changes as it gets passed down consecutive generations, like the game Chinese Whispers. We can’t rely on our memory, as a true representation of the past, as we often look back with rose tinted spectacles, or at least alter our recollections to fit in with our contemporary lives.

I find it fascinating to consider the possibility that what we are led to believe as fact is likely to have been tailored to suit the ruling classes and political agenda of the time. It is possible to imagine that everything we know about anything could technically be fictional. I don’t want to force my narrative upon anyone so there is this blurring of documentary and fiction.

The idea of time seems to be interesting to you. I’m thinking about how you juxtapose and layer images across historical time; and across medium (from found footage to material you’ve shot yourself).

One of the things that appeal to me about the moving image is the ability to jump around in time. We are conditioned to think of film as a strictly linear medium, with a strict beginning, middle and end because that has been the dominant way film has been used to tell a story, but life is not one straight linear path, and often it is the side roads or tracks that lead to the most interesting places.

What does the Wolverhampton show mean to you? It is your home town?

Yes. It’s my home town gallery, and one I have visited for as long as I can remember. The work is about the area in many ways. The stories and influences are about local people or happenings, about childhood memories. I spent many years trying to escape this place. My childhood coincided with Thatcherism. Of course I didn’t think about these things growing up but after spending many years away I found it incredibly interesting going back. There was suddenly this realization that the place shaped who I am which in turn shapes the kind of work I make. I recall my father on picket lines and noisy confrontations with the police. Factories were closed down, jobs lost and what exists today is a result of subsequent generations relying upon the system. Today the place like many other former industrial towns is a concrete wasteland with a ridiculous amount of retail parks filling the demand for people to spend money they have not got on stuff they don’t need. Screenshot from ‘The Impossibility of Living in the Present’ (2012).

Screenshot from ‘The Impossibility of Living in the Present’ (2012).

The footage of the urban landscape in ‘The Impossibility of Living in the Present’ is interesting in terms of wastelands.

The footage taken through the fence was outside Eagle Works – an artist led studio space in Wolverhampton. It’s a view of a derelict landscape that used to be a hive of activity with factories and industrial buildings providing hundreds of jobs. The site has been acquired by Sainsbury’s who are building its second supermarket in the city. At the time of filming Eagle Works members were complaining about the proposed supermarket blocking all natural light to its studios opposite. Still, at least some jobs will be created I guess.

I see a strong relationship between art and politics in your films, but not politics in a didactic, ‘fist in the sky’ kind of way.

Sometimes you look back and things aren’t so different than they were many years before. That’s why I included Edward Heath’s speech in ‘The Impossibility of Living in the Present’. My work is becoming more political. There is a need for political art in places where people are denied the right to free speech, or are persecuted. In this country, we still live with the legacy of Thatcherism. Of course, my view is that of someone from a working class background. I currently have a video in production that I’m calling a Public Information Film with its tongue firmly in cheek. It will offer an alternative, more critical (and cynical) view of life in Britain. This may actually become the final part of the trilogy.

Screenshot from ‘The Devil’s Haircut’ (2013).

Screenshot from ‘The Devil’s Haircut’ (2013).

Exhibition closes 14 September 2013 www.wolverhamptonart.org.uk

All images courtesy of Stuart Layton.