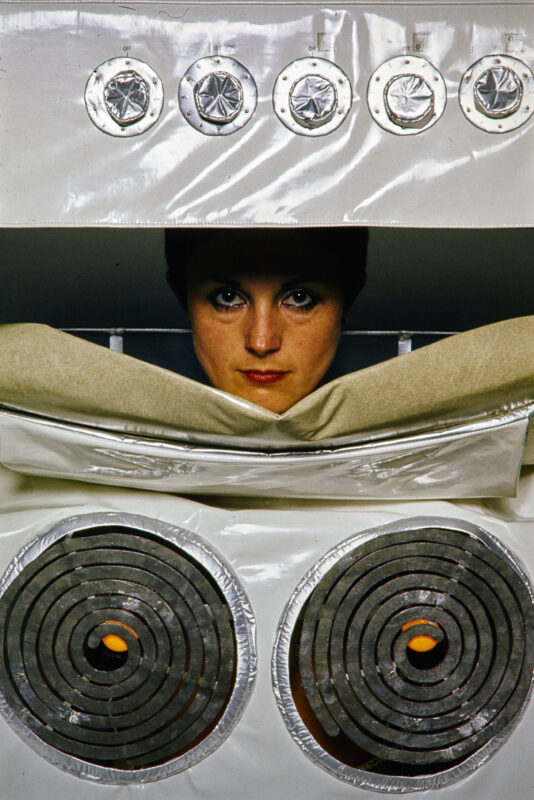

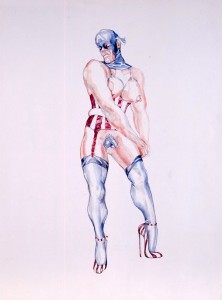

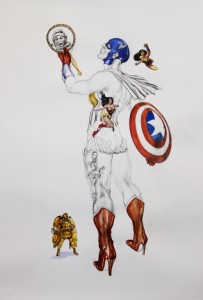

‘Captain America’, 1971-1997. Watercolour and graphite on paper.

This week Margaret Harrison was awarded the prestigious Northern Art Prize 2013 (www.northernartprize.org). She was nominated for the prize by Kate Brindley (Director at Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art). The judges commented: ‘After much deliberation, we have decided to award the Northern Art Prize 2013 to Margaret Harrison for vital new work that reflects on her 50 year career at the front line of art and activism’. The Northern Art Prize exhibition runs through to 16 June 2013 at Leeds Art Gallery. Harrison’s installation ‘Reflect’ (made especially for the Prize), also won her the public vote. Work is on show at Leeds, together with the work of the other artists shortlisted: Emily Speed, Rosalind Nashashibi; and Joanne Tatham and Tom O’Sullivan (www.leeds.gov.uk/artgallery).

Margaret Harrison receives the Northern Art Prize at the Leeds Art Gallery on Thursday night.

Born in Wakefield (Yorkshire) in 1940, Harrison is one of the most important British artists to work in relation to politics, activism and women’s movements. She is a significant figure in the story of feminism and its relationship to art and politics in Britain, and has been situated within the context of important current (and international debates) about global feminisms. In recent years Harrison’s work has been exhibited on shows central to contemporary debates about feminism and art practice around the world: notably the 2007 touring feminist retrospective ‘WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution’ (at MOCA, Los Angeles and MoMA/PS1, New York) and the 2009 exhibition ‘REBELLE: Art and Feminism 1969-2009’ (at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Arnhem, the Netherlands). Her work also appeared at the 11th Istanbul Biennale in 2009.

In London, solo and group exhibitions have been curated by Beverley Knowles (www.beverleyknowles.com) and Payne Shurvell gallery (www.payneshurvell.com). She is also supported by the Ronald Feldman gallery in New York (www.feldmangallery.com) and Silberkuppe in Berlin (www.silberkuppe.org). Major public institutions including Tate, the Victoria & Albert Museum and the Arts Council of Great Britain have collected her work. Harrison lives and works both in San Francisco and Cumbria. Between 1997 and 2008 she was Research Professor at Manchester Metropolitan University.

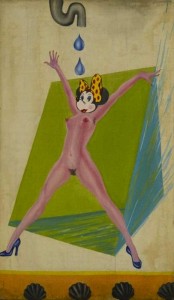

‘Study for Women of the World Unite, You have Nothing to Lose but Cheesecake’, 1969-’70/2010. Graphite on paper.

Harrison’s practice (which encompasses mediums from painting, drawing and collage to installation) speaks to the concerns of the 21st century, its politics and the repetitive re-inscription of political violence (visible and public; insidious and veiled). Mixed-media works such as ‘Rape’ deploy a research process, found materials, images and texts that open up the ways in which we think about violence, in texts and images. Harrison trained at the Carlisle College of Art (1957-61); the Royal Academy Schools, London (1961-64) and the Academy of art, Perugia Italy (1965). Her work is beautifully made, and often deploys humour as a critical strategy, bringing together the political and poetic capacities of visual images in ways that ask us to reflect carefully on the nuances of how it is we experience the power and presence of images in our everyday lives.

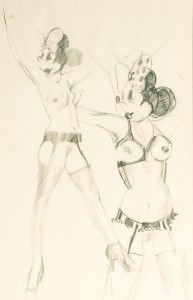

‘He’s Only a Bunny Boy But He’s Quite Nice Really’, 1971 and 2010. Ink and graphite on paper.

Harrison (who founded the London Women’s Liberation Art Group in 1970) has personal experience of just how powerful and threatening visual images can be. In 1971 police raided and closed down her first solo show in London on grounds of public indecency (they objected to her depictions of men). The show famously included a depiction of Hugh Hefner in a Bunny girl outfit (the work went missing during the course of the furore). Harrison recently recreated the image of Hefner for a show at Payne Shurvell: ‘I am a fantasy’ (2010).

Yvette Greslé interviewed Margaret Harrison after the opening of her solo show ‘On Reflection’ at Payne Shurvell (www.payneshurvell.com) shortly before she was awarded the Northern Art Prize on Thursday night (23 May) at an event at the Leeds Art Gallery. ‘On Reflection’ at Payne Shurvell, London closes 20 July.

‘What’s That Long Red Limp Wrinkly Thing You’re Pulling On’, 2009. Watercolour, coloured pencil and graphite on paper.

There are connections between the work at Payne Shurvell and earlier work from the 1970s. What was the impetus for this new body of work?

I’d been nominated for the Northern Art Prize, and was thinking about work for that. In 2012 I had a solo show at Silberkuppe gallery (Berlin) called ‘Fear Forgetting’. They’d asked about an earlier work called ‘On Greenham Common’. This was a work about the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp in the ‘80s (the women were protesting nuclear weapons at RAF Greenham Common). At Silberkuppe, they said they wanted to bring this earlier ‘occupation’ back, and they wanted the fence (an interpreation of the perimeter fence from the Greenham Common base). I said: ‘Why do you want the fence?’ They said: ‘Because the Biennale is going to be around the Occupy movement’. We did get a 13 foot fence made, and I did a new piece to go with it so that there would be a context. It was like a documentary thing but with images. And when it went up I thought: ‘I should have put a mirror behind that’. Because it’s about reflecting back things from the past, and reflecting what happened then. There was an action by the women of Greenham: each brought a mirror, surrounded the base and shone the mirror into the base so that the people in the base could see what we were seeing. So it was reflected back to them, and they could see themselves in these mirrors. I thought: ‘What a great idea’. That event became like an artwork. I thought: ‘Ok, I’ll re-do it for Leeds. The whole thing is about reflection. The exhibition for Leeds is called ‘Reflect’ and the installation that developed out of the Silberkuppe show is called ‘Common Reflections’.

‘Common Reflections’, 2013. Concrete posts, wire, mirrors, corrugated zinc sheeting, found materials and objects.

I’d also been reading Tennyson’s poem ‘The Lady of Shallot’: great poem but totally depressing. I started thinking about the poem, and I did a bit of research. In the Victorian period the picturing of ‘The Lady of Shallot’ was about the containment of female sexuality.

The Pre-Raphaelites were fascinated by ‘The Lady of Shallot’.

The Pre-Raphaelites were totally fascinated by that poem. I drew on ‘The Lady of Shallot’ by John William Waterhouse and made ‘The Last Gaze’. But the Lady of Shallot didn’t see the world. She saw it through a mirror. And I thought actually that’s the way a lot of us see things. Slightly at an oblique angle we don’t quite get to the reality of it. And the painting has this: when the web is blown apart then he’s got the threads winding around her skirt, imprisoning her. And I thought: ‘I’m going to use that and I did a double image of it in reverse. One side is black and white and the other is colour. As I was working through this, Payne Shurvell were suggesting I did a show with them. And I thought I should actually pick up on these themes, on the idea of the mirror image. I’ve inserted the Lady of Shallot in the image of Betty Page at Payne Shurvell: Betty Page in the classic pose. I thought: ‘this is about the dilemmas of having a kind of sexuality that actually you’re quite pleased with, but also where there are traps’. I put the Lady of Shallot on Betty Page’s back. And then I put other things around.

‘The Last Gaze’, 2013. Harrison’s painting reflects on ‘The Lady of Shallot’ by John William Waterhouse (1894). The Waterhouse work is in the collection of the Leeds Art Gallery.

I’ve been thinking a lot about that, about female beauty, and its meaning. It has this power but there is another side to it that is open to exploitation.

Yes, all this trafficking that’s going on at the moment.

I was thinking about it in terms of the history of women and cinema: Hollywood, its history, its system.

Exactly. Do you ever watch Coronation Street? There are two images from the early Coronation Street. There were two main woman characters. That was what was the good thing about that soap. It actually promoted the female characters as not just sitting around waiting for the men. You had the barmaid. You had characters scheming and getting up to all sorts of things. You had this woman Ena Sharples (a ‘battleaxe’). And you had Elsa Tanner who was the glamour puss of her time. There’s this image of Elsa Tanner looking into the mirror. I thought: ‘This is perfect’. I printed it onto heavy paper: then reversed it and printed it. Around her are all these images including Gloria Swanson against a mirror. I also used an image from the Vietnam War. Bits of collage which I then reversed on another image.

‘I’ve Always Had a Thing About Fashion’, 2013. Diptych. Giclee print, collage, watercolour & acrylic on paper.

What’s also interesting about the work at Payne Shurvell is that it’s a bit like a bricolage. You seem to gather all these bits and pieces, which appear incongruous.

Normally you would think they’re incongruous because you would only focus on one issue or one thing. But what I try to do is bring things together.

I’m thinking about how you take a male body, and then mix up the markers of gender identity (breasts and so forth). You also draw from a style and imagery that we associate with comics but at the same time your work is very finely wrought. There’s this mixing and blurring going on and that’s what is interesting about the work.

Now with the World Wide Web everything is connected.

But that sense of inter-connection was there in the earlier work. How did you come to be interested in pop culture, comic culture, celebrities, things that are so familiar and part of everyday life, and imagery that is still relevant today?

Because it was so familiar. I lived around Notting Hill Gate and there were these comic book shops which were: ‘Oh my god look at that’. You hadn’t seen that sort of stuff. And then it got me thinking: ‘Oh it’s American culture’. It was there all the time and you didn’t quite think: ‘America’. But it was American culture and you were breathing it in. And the Vietnam War was going on. I put the Vietnam war back into the work at Payne Shurvell, and the 1950s and ‘60s. A lot of American artists were around, and so you became familiar with all that stuff. One of my earlier pieces was of Captain America of course. And it was the notion that in the comic books Captain America was supposed to be doing good. But then you had this other flipside: ‘actually they’re not doing so much good’. A lot of people didn’t like that of course. I thought: ‘I’m going to challenge that’. But also I thought: ‘I’m going to challenge this notion of masculinity’. We were in the woman’s movement and we were going through notions of different sexualities. Some of my friends decided they were gay. And we would never have thought of that before.

What do you think opened up the way you were thinking about masculinity and femininity?

I think it was because there was this mixing up of things. A lot of American artists came over and people were doing performances. At the Miss World competition (in London, in 1970) we did street performances, and there was a group of men who came dressed as Miss World and did performance and supported us.

‘Women of the World Unite, You have Nothing to Lose but Cheesecake’, 1969-’70/2010. Coloured graphite and graphite on paper.

What was hidden or veiled was becoming more visible?

The sub-culture was rising to the surface and as art students we were all experimenting with all sorts of things. We went to Liverpool where John Lennon was playing. Music and fashion were intermingling. Prior to that if you were a guy you got the most boring clothing you can imagine. But now we had Mick Jagger in a dress dancing in Hyde Park. It was very liberating.

I wonder how these kinds of social shifts come about?

It was ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ (laughs). It was Elvis Presley: ‘Heartbreak Hotel’. When you heard that it was: ‘Where did that come from?’ The other thing was that it didn’t come from an upper class thing. Britain was (still is) very class led. We’re back to it aren’t we? With our present government. There had been that control for quite some time, and then there was that liberating thing of the art schools opening up. At the same time there was all this music coming from America and Elvis Presley. You just saw another side of things.

‘Captain America’, 1971-1997. Watercolour and graphite on paper.

You started looking at masculinity in a different way? I think what’s interesting about your work is how you engage the question of masculinity. That was very much part of the 1990s – all the work around Queer history, theory, identity. There was the ‘Women’s Images of Men’ show at the ICA in 1980. But I’m very intrigued how you – at that time – came to masculinity. Because, for me (my generation) your images are legible because of the ‘90s.

I buried that stuff when I went to California (nobody knew what I was on about). Then, in the ‘90s, in America, I was asked by the University of California whether I’d do a show. I brought that earlier stuff out and they said: ‘Oh we’ll have some of those’. They really got into it and were really enthusiastic.

The ‘70s pieces, were resurrected in the 1990s?

Yes, they were resurrected in the ‘90s. In ’93. I only showed three I think. But there was a positive reception [the exhibition was at the Richard Nelson gallery, University of California].

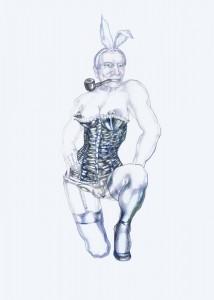

Banana Woman, 1971. Coloured graphite and graphite on paper.

The Hugh Hefner piece and the controversy around it, is constantly referred to. You were also critiquing gender issues as much through female figures?

Yes, I did it equally. I also did some very rude ones (laughs). There was one I sold recently: a woman dressed in the usual garters and suspender belts with her legs open. And it has this text: ‘if these lips could only speak’. There are also two works of women that Beverley Knowles showed: two women in an ice-cream cone. I said we have the right to our fantasies as well. It’s trying to figure out if its equality in all sorts of ways. It’s not just a wage equality thing. It’s also about having equality in other ways.

It’s only now that that’s part of public discourse – that women can look at men’s bodies, or think about pornography for women.

There is a professor called Linda Williams who came over here in the late 1990s. She was a professor at Berkley, California, and she was looking at pornography as a sort of repressive thing, and then she started thinking ‘hang on there must be something in this for me because I’m not responding in the way that you would expect’. She brought out a book and they called her the porn professor when she came over here. In California they didn’t call her that. She was a distinguished academic but when she came here the headlines were ‘porn professor’. She discusses that whole thing of women and pornography.

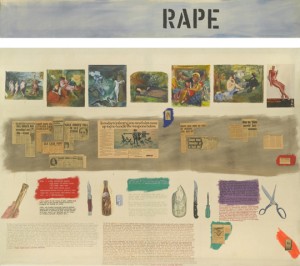

‘Rape’, 1978. Acrylic, newspaper clippings, marker, pencil on canvas.

How do you think about women’s issues now? When you speak about your work, and about politics, I hear a narrative that swings backwards and forwards between past and present. I’m thinking about the ‘Rape’ work. There seem to be so few works dealing with rape, and it was especially interesting for me coming from South Africa where rape is so ubiquitous. It’s so much part of women’s histories and the violence enacted upon women’s bodies in that country. Feminism has shifted so much socially and politically (but it does depend on where you are in the world). It does feel at times as though we are regressing (I’m thinking about recent stories about rape and trafficking).

There was a discussion on Woman’s Hour I think and people were saying there’s no need for feminism. Actually it has become more personal and violent. The attack is on woman’s sexuality and their bodies. There is all this trafficking, and the grooming of these young women. I brought the rape in India into one of the pieces. I put that image of protestors holding candles on the leg of Betty Page; and I’ve also referred to it in another piece where they put these bandages around their mouths. And that’s exactly what we did in the 1970s. So I just thought: ‘Oh my God. They’re using the same devices of performance that we did. Only they don’t look the same’. That was what was so interesting about the show in the Netherlands (‘Rebelle’). There was that artist from South Africa photographing transgender men (beautifully photographed). I thought it was quite dangerous work to do that work in her context.

Yes, Zanele Muholi. You must have read about art and censorship debates in South Africa, and the violence towards lesbian women in particular (so-called ‘corrective rape’).

Zanele came to see my work (the ‘Rape’ work) and said ‘oh this is a very important piece’. That was so nice, from this young woman.

‘Very Close to Getting in Touch With my Masculinity’, 2013 (part of a diptych). Graphite, watercolour & collage on paper.

In many of your works you show up the ways in which images from popular culture aren’t simply innocent and benign. The images are very beautiful but at the same time there are other things going on: the mixing up and re-assembling of bodily signifiers of gender identity for instance.

I do like the beauty of the drawing and the paint. I do like the materials and a lot of people do. It’s a way of drawing people in. Instead of the ‘fist in the sky’ all the time. I find a way to discuss it which is not going to put people off.

When I did the ‘Bodies Are Back’ show at the Intersection for the Arts in San Francisco (in 2010) the curator said this work is perfect because their place is right in the middle of the gay community, and they hadn’t found a way to relate to that community, and the young people around there. Their thing is they create a play that might go with the theme of the exhibition and vice versa, and they also have workshops etc. They had a workshop for an LGBT group so he showed this group my work, and they were just delighted. It gave them permission to do what was important for them. They said ‘oh we can switch body parts around’. And they did. They did these giant pieces for the Underground.

It’s interesting this bricolage of body parts: the way you gather bits and pieces and mix them together. Do you have an intellectual position on that process?

Some of the time: it’s making sense of the notion that you can’t separate off the war against women and politics. It’s all there together, and very much so in the United States. A couple of years ago – just before the last Obama election – the Republicans had gone so far to the right that they were really trying to close women’s rights down and they talked about justified rape. When is it justified? And they tried to stop including women’s health issues in the health laws Obama was trying to bring in.

The ‘Rape’ work stages these issues very powerfully.

That work goes on show all the time now. The first place it went on show was at the Middlesbrough Institute of Modern art (MIMA). The Director of MIMA, is Kate Brindley, who nominated me for the Northern Art Prize. We did a conversation piece last week actually in Leeds and she brought up the fact that the ‘Rape’ piece was talked about such a lot. It had a major complaint from a judge who complained about its criticism of the judiciary system. You’re supposed to decorate. You’re not supposed to engage.

In the ‘Rape’ piece there’s a research process. You’re taking things that were actually published in the media. It’s a debate through a constellation of media texts and images, and images through history. You make a considered argument using these images and texts.

If you draw or paint a woman who’s just been raped it just looks as though she’s lying down. You can’t get behind the issues.

‘Very Close to Getting in Touch With my Masculinity’, 2013 (part of a diptych). Graphite, watercolour & collage on paper.

In the work for the Payne Shurvell show, you foreground current issues, including the question of rape.

There’s another work of Captain America. But he’s kind of altered. You can tell he has breasts, and he’s facing away and looking into the mirror. And in the mirror a woman is crying. I put her in the mirror together with his overtly sexualised (actually ambiguous body). I’ve seen women crying so much over the last ten years through all these different wars. Rape is a weapon of war and it’s repeated over and over again.

It’s interesting how in the work you overlay political, historical, cultural narratives. Why do you think the body is such an important vehicle for you?

It is a kind of device. I’ve used it in the piece in Leeds. I wanted the popular culture to be there. What is she looking at? What are they looking at in the mirror? What is being reflected back? Can we have it reflected back?

Body politics is very present in your work. The body is a site through which to explore politics and violence on a wider scale. Violence is inscribed on the body in all kinds of ways from rape to the pressures of fashion and celebrity culture.

Well it comes back to the body.

You open up issues that society and political ideology like to smooth over and make ok but it’s not ok. Rape (and its ubiquity) is a serious issue, and it’s worldwide.

The Mumbai story was shocking. But what was interesting about those protests is that young men came out and protested because they don’t want that label.

‘You Looking at Me? You Looking at Me?’ 2013, (part of a diptych). Graphite, watercolour & collage on paper.

What do you think about politics in the UK right now? Is there any work that you’ve made that talks about what’s going on here politically?

The one thing that I was drawing out was that Margaret Thatcher had died. I refer to Orgreave the big miner’s strike at the coking plant. Thatcher sent in troops and police. She totally smashed this community. I brought that out in the work. At the same time the conservatives were having this regal funeral while other people were remembering what they had lost.

What do you think about the politics that got mobilised around Thatcher’s funeral (and the tremendous anger). It was as though something that was just underneath the surface exploded around her death. On the one hand, in your work, you’re always thinking about the present, and on the other you’re thinking about the past and its relationship to what’s happening today.

You learn from the past. In order to think about what’s happening now we need to make the connections to previous actions. It’s not exactly the same though because the strategies and the tactics change.

‘Common Reflections’ at Silberkuppe gallery, Berlin in 2012. An earlier version of the installation at the Leeds Art Gallery.

Is there something about repetition that interests you? The 60s and 70s was this moment for art, activism and politics. But now in the 21st century it feels as though the world is regressing; that society and politics is becoming more conservative. There is a constant sense of repetition. One feels at a loss for words. What is there to say? How does one find a language to move past this because we keep coming back to the same thing? Is there something that interests you about that in your work?

It must do because I keep coming back to it. I was in the Istanbul Biennale in 2009. I was the only one from Britain, the only artist, and they showed a piece from the 70s. I said: ‘Why do you want this?’ And they said: ‘We thought it was important’. There were three young women from Croatia from Zagreb who were invited to curate the show. When we went round the show it was very déjà vu. All of the work from Eastern Europe, Iran and Iraq. They were doing very strong, political work. And some of the issues that they were dealing with were very similar to us (looked different, but was the same in many ways). There has been a lag in other countries. In Eastern Europe the feminist movement is quite upfront now. They keep being put in prison. You think: ‘Oh they didn’t know what we were doing? But they do. So they’re now re-inventing the whole thing. They’re starting in the same way. But they can now lean on us. We felt as though there was nothing. I think it’s useful for people to look at that, and then I can put it back into the work as well.

Do you see anything interesting in the work of younger generations of women. A lot of recent performance art speaks to what was happening in the ‘70s.

When we were doing stuff in the ‘70s there was no art market. It collapsed at the end of the ‘60s so you thought: ‘ I might as well do something interesting rather than just decorating things’. That’s when we got deeply into it. It’s a little bit distorted because the art market still keeps going. But if you were to look around and talk to younger women and men they’re struggling. And that motivates them into thinking about other things. It’s very expensive to go to art school.

‘Common Reflections’, at the Leeds Art Gallery, 2013.

The Northern Art Prize exhibition runs through to 16 July 2013 showing work by Margaret Harrison, Emily Speed, Rosalind Nashashibi and Joanne Tatham & Tom O’Sullivan www.leeds.gov.uk/artgallery

Margaret Harrison: On Reflection closes 20 July www.payneshurvell.com