Heart of glass … Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka’s glass models of aquatic creatures were made with purely scientific intent. Photograph: James Turner/Amgueddfa Cymru National Museum

Consider this curious item of furniture, which belongs to the Geffrye Museum in London and appears at Turner Contemporary, Margate, as part of Curiosity: Art and the Pleasures of Knowing. The object in question, at once austere and elaborate, is a cabinet of intricately carved ebony that stands on eight slender legs and opens to reveal a prismatic array of interior drawers and doors, rendered in fruitwood and ivory. The thing is said to have been made by the renowned Dutch craftsman Pierre Golle, though we cannot be sure. What’s certain is that it was bought in Paris in 1652 by Mary Evelyn: wife of the polymath John Evelyn, who used it to store prints and small items. The empty cabinet is a reminder of the capaciousness of Evelyn’s intellect and imagination: by the time he died in 1706, he had completed not only half a million pages of his celebrated diary, but treatises on medicine, mathematics, air pollution and the cultivation of trees. He had even written a discourse on salads.

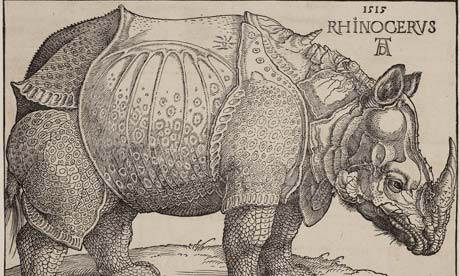

According to the jargon of his age, Evelyn was a curioso: one of those learned individuals whose acquisition of knowledge and things was marked as much by untamed variety as depth or precision of inquiry. And his cabinet is an emblem of curiosity itself, a modestly scaled descendant of the wunderkammer, or cabinet of wonder, that the Renaissance had invented to house its discoveries, natural and artificial. The great cabinets of curiosities, such as those that belonged to Ole Worm and Athanasius Kircher, were in fact whole rooms, precursors of the modern museum, in which objects drawn from far-flung places and times, from all disciplines and art forms, might inhabit the same physical and mental space: animal specimens, minerals, crystals, fossils, ethnographic objects, works of art and mathematical or scientific instruments. Evelyn’s sober cabinet is the microcosm of a microcosm – infinite riches in a little room.

The historical cabinet of curiosities is one inspiration for Cabinet magazine: a quarterly of art and culture, founded in New York in 2000, for which I’ve worked as UK editor for the past 10 years. When I first came across Cabinet I was mystified by its mix of artists’ projects and seemingly scholarly writings on topics such as the meanings of orange as a colour, the names paint manufacturers give to their products, and the industrial ruin of Hashima Island, near Nagasaki. It was partly to figure out just what Cabinet was meant to be that I took it home and wrote straight away to the editor, Sina Najafi. I learned later that he’d had in mind Documents – Georges Bataille’s surrealist journal of the late 1920s – as well as great essayists such as Susan Sontag and Roland Barthes, but also a touch of Mad magazine in its prime. Above all, Cabinet was committed to curiosity, and to its serious and playful expression across the arts and sciences.

The magazine has published special issues on a wild variety of themes, including laughter, hair, ruins, electricity, dust, friendship, bubbles and learning itself. But when I was invited to conceive and curate an exhibition based on Cabinet’s sensibility, it was clear it had to be about the fundamental, animating principle: curiosity. It would have to mix old and new, historical artefacts and the work of contemporary artists, and it would have to be as much about mundane curiosity, wonders discovered amid the everyday, as about modern equivalents of the oddities that stocked the early-modern cabinets. That is how we have arrived at a show that includes works as historically diverse as Leonardo da Vinci’s drawing A Cloudburst of Material Possessions and Nina Katchadourian’s photographs made on long-haul flights with her camera phone and whatever materials come to hand.

Among the obsolete meanings of “curiosity” is an excessive care for small things or details. It’s a charge that was levelled at the virtuosi of the 17th century, not least Robert Hooke, whose Micrographia of 1665, with its fold-out engraving of a close-up flea, is in the exhibition. (Hooke didn’t only train his microscope on minute naturalia: there’s a passage in his book where he looks at full stops, and finds they resemble “smutty daubings on a matt or uneven floor”.) Among the contemporary artists in Curiosity, Susan Hiller presents Split Hairs: The Art of Alfie West, her vitrined collection of tiny artworks by West, who in the 1970s earned a place in the Guinness Book of Records for having split a human hair lengthwise 17 times. At the furthest extreme of scale, Katie Paterson’s History of Darkness collects images of the night sky, all void and black, from observatories around the world.

Curiosity involves very close looking, but also intricate manufacture. In the late 19th century, Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka, a father and son based in Dresden, made countless glass models of aquatic creatures for museums of natural history in Europe and beyond. Working at first from images by Ernst Haeckel and Philip Henry Gosse (whose illustrations are also in the show), and then from live examples in a large aquarium, the Blaschkas produced simulacra of such astonishing vividness and detail that they are still frequently displayed without comment, as if they are the real thing. The Blaschkas in no way thought themselves artists, but their models – jewel-like or glaucous, spiny or tentacular, made with purely scientific intent – are also part of a monstrous aquatic imaginary, pursued by later works in the show: Jean Painlevé‘s underwater films (Bataille put these in Documents in 1929) and Aurélien Froment‘s recent film of a billowing jellyfish that resists zoological categories.

The exhibition has a strong natural-historical strain. Dotted around at Turner Contemporary are hybrid taxidermal inventions by Thomas Grünfeld: a sheep-and-st-bernard cross, a penguin that tapers to an iridescent peacock’s head. But historical taxidermy has already supplied an instructively bizarre specimen: the overstuffed walrus from the Horniman Museum in south London, a creature with the sculptural presence (and the weight, it turns out) of a Henry Moore bronze. The animal was shot by the Canadian zoologist and hunter JH Hubbard and exhibited in Kensington in 1886; its trip to Margate will be its first outing since the Horniman bought it in 1893. Like many specimens of that era, its folds were filled by insufficiently informed taxidermists, so that it swells fit to burst with evidence of curiosity and its limits.

The walrus, of course, reminds us of Alice: “Curiouser and curiouser”. Fiction, fantasy and innocence have long been associated with curiosity and curiosities, and we wanted the exhibition to reflect this. The Irish artist Gerard Byrne has for more than 10 years been working on a formally varied project about Loch Ness, whose apocryphal tenant he takes to be an emanation of the twin histories of photography and research. In Byrne’s own photographs and footage, the shores of the Loch seem to produce an absurd commentary on Nessie, that very modern monster, and on the odd affinities between enthusiasts of the creature and contemporary artists with their archival urges.

The original cabinets of curiosities were as much private chambers in which the world might be invented anew as repositories for definitive objects. The most resonant example is probably a collection that belonged to another renegade surrealist. Over several decades, the writer Roger Caillois amassed a collection of stones – among them agates, alabaster, quartz and jasper – in which he spied faces, phantoms, landscapes and ravishing abstractions. At the same time, as Marina Warner put it in an essay on Caillois for Cabinet in 2008, he exulted in “their inscrutability and their lack of affect, their silence, their sheer stoniness”.

Warner has been an essential adviser for this exhibition. In an essay for the catalogue, she points out that despite the reality and the fantasy of the avid male curioso and collector, curiosity itself has long been considered a female vice: the besetting sin of tattletales, gossips and domestic spies. There’s an example of the last in the show: the listening servant in Nicolaes Maes’s 1655 painting An Eavesdropper with a Woman Scolding, which suggests that the whole ordered space of the Dutch interior is a machine for scrutinising the secret lives of others.

After scale, natural science, fiction and disreputable prying, a malign secrecy is the final major theme in Curiosity. Its oddest expression comes courtesy of the Center for Land Use Interpretation (CLUI), a research organisation based in Los Angeles. In 2011, the centre was bequeathed a collection of ephemera from the US nuclear-weapons facility at Los Alamos. The artefacts had belonged to one Ed Grothus, a former technician at the lab who had grown disillusioned with his place in the military-industrial complex and left to become an anti-nuclear campaigner. Invited to take part in Curiosity, CLUI has lent seven Rolodexes containing the business cards of contractors hired by Los Alamos: mundane functionaries at the secret heart of the Cold War.

Last year Cabinet published, a little late, a 500-page anthology of its first 10 years, entitled Curiosity and Method. The magazine remains committed to heftily actual objects in the material world, as well as talks and exhibitions at its Brooklyn gallery space – and now for a time on the English seaside. This in an era when our inquisitiveness has migrated online, or we are so distracted by our technologies that we no longer know how to know the world. The truth, of course, is vastly more complex: the cabinet of curiosities was always already a web of immaterial hunches and links and allusions as well as a real space full of real things. And like the internet, it was partly to be distrusted and partly to be marvelled at for the profusion of things that might be known, and the responsibility it placed on the curioso to judge as well as to wonder.

• This article was amended on 21 May 2013. The original sub-heading wrongly referred to Da Vinci rather than Leonardo, in contravention of the Guardian Style guide. This has been corrected.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.