Yvette Greslé chats to Eli Cortiñas (b.1976) at the private view of her first solo show at Rokeby gallery, London (www.rokebygallery.com). Cortiñas was born in Las Palmas de Gran Caneria and currently lives and works in Berlin. She studied at the European Film College in Denmark and the Academy of Media Arts in Cologne. Her work was recently included on Videonale 14 (Kunstmuseum Bonn), and she has exhibited, among other places, at Centre Pompidou, Paris and the Guggenheim Gallery, L.A.

‘Awkward studies and a decent take on serious matters’ runs through to 15 June 2013.

Let’s begin by talking about the film ‘Confessions with an open curtain’.

The curtains are the driving force of the work. I was looking for curtains from films that talk about, or portray theatre life. When you watch these movies (I have watched so many) you start to see certain conventions to do with the telling of life in the theatre. Film took so much from theatre, and you find so many references to this.

I didn’t just choose films with beautiful curtains: I wanted to have an internal path that keeps the work together for me. You might not see it but (for me) this path binds the whole film together. I don’t get too carried away with things that are just beautiful. I think when it comes to found footage there is a dilemma: you love films and you want to show the beauty of them but you are working towards something that is yours, with your signature. I have works that have taken me over a year to make, and they are just 11 minutes at the end.

In making this work, were you referring back to films from the 1950s or ‘60s?

I was not so much looking for a certain period (of course, visually I wanted the images to fit). The work is also about referencing painting. It was very interesting for me to reference the women from the back, something I know from very classical painting. When I worked in film I was an editor, and it was always about the face. They always say that you can only show emotions and create emotions by means of the close-up (and the emotions of the face). I was curious to know the extent to which I could put a motif or a convention associated with classical painting into a moving image, and still create a dramatic charge.

I am not a painter but I am interested in making work that comes close to pictorial representation (in painting) in a moving image.

You were thinking about the vocabulary of painting, and also the vocabulary of film? You have worked as a film-maker?

I studied film before I studied art. It was when I became a documentary editor that I realised that documentary is actually fiction at its best. Even reality has to be orchestrated; orchestration is what interests me. You have hours of footage, that you then select from and structure into a story. It opened my eyes to archives, and working with material that already exists. Before that I worked with short films. I was interested in being a film-maker. But I was always aiming for a more experimental approach to film.

How do you find your way through the found footage you work with? What is the process of constructing a work from this material?

When I work with found footage I try and put restrictions on myself because it can be absolutely seductive. In cinema, you have these wonderful actresses and performances. Directors have a certain vocabulary. I don’t want to just fall in love with this material and simply reference it. I want to take it, and fight for finding my own voice in there.

I can see you’re not just taking found footage and presenting it in an uncomplicated, uncritical way, taking it and then rolling it in one after the other. You make interventions with pacing, and with sound. Do you crop?

I don’t crop. I use slow motion. I had to use slow motion in this particular film with all the women because I didn’t want them to turn around. I like to be open about my tools. You as a viewer know my tools, but I still want to drag you in emotionally. The film is not a real history because there is no clear narration. But in all my works it’s also about two generations of women talking to one another. One a bit older, maybe a bit more experienced.

You appropriate sound but then you recast it. You don’t use sound in a linear way. Sound is sculptural in a sense.

Yes. I work in Final Cut Pro. I collage with sound. I cut words together that don’t belong together. The sound in my videos are almost never in synch with the images. I move the sound around, re-assemble it, cut it at the moment you wouldn’t expect it to be cut.

Do you write a script for yourself? A sound script, and an image script? You orchestrate the work very tightly?

Yes, absolutely. I write everything down. I work on the sound and images together. I work out how I’m going to lay out the sound before. I set out the voices, the dialogues … I think about how I’m going to make my characters say what I want them to say.

Do you ever let chance enter the mix?

No. Of course, sometimes there is trial and error. It happens sometimes. But mostly not.

The only time the images are muddled with are through slow motion?

Yes, slow motion and juxtaposition. I also work a lot with two channels, or three channels. Then it’s not just about time, and linear editing. It’s also about space. I explore what happens when I work with two of the same images on different screens but start one a bit earlier or later. I play with that a lot.

I’m interested in how you make use of Joseph Mankiewicz’s ‘All about Eve’ in your soundtrack. What strikes me about films like ‘All about Eve’ is that they’re actually quite self-referential and critical. We think film-making that speaks critically to what it is to be a woman comes later but what is interesting about films like ‘All about Eve’ is that there is some critique and irony.

Yes, absolutely. But at the end of the movie she’s happy to get engaged and married and be domesticated.

There’s also in ‘All about Eve’ the theme of ageing. Sometimes when I look at some of the images of the curtains in your piece I see a shroud, or they seem to take on a life of their own. The effect is quite uncanny.

I am very interested in those sorts of dialogues. In 2008 I made my first found footage film. Before that I was working with documentary material I shot, and mixing it with found footage (I was buying 16mm film and Super 8 from places like eBay). It is very interesting trying to create a new context for these images. Sometimes knowing where they come from, and sometimes not. Working with cinema makes you think a lot about film history and popular culture. It’s interesting to think about the time in which films are released, about the impact they have. Louis Buñuel’s ‘Belle de Jour’ is a film that had an impact, on an erotic system, and the way women were seen.

Did you use ‘Belle de Jour’ in ‘Confessions with an open curtain’?

No, but the Catherine Deneuve film I do use is called ‘Hustler’. Her character tries to make it in America as an actress but to earn money she becomes a prostitute. It was with Burt Reynolds. She goes to the balcony in a kimono. I was looking for an image of a woman from the back, and I had this material for many years already. I build large archives of material. I also used an image of Ginger Rogers; and I used material from Hitchcock’s ‘Topaz’.

You are like a historian. You build your own archives. You gather material for your archives. Some of the material you deal with is not documented at all. It’s found and anonymous. And some of it is known and visible (from cinema). As an artist you’re finding your voice through this. Not just a creative voice but also a critical voice. You’re searching for a counter-archive; a counter-history?

Yes, absolutely. I’m busy on a piece where I’m trying to mix American film noir with Italian neo-realism. I have been putting Fritz Lang and Visconti together. It’s a totally different way of story-telling. These are two different histories, from two different places, and they happened at the same time. I love Italian neo-realism – Pasolini, Visconti. I started putting Italian neo-realism with the deepest film noir (looking at material with Ingrid Bergman and Barbara Stanwyck). It seems so disrespectful, this mixing, but when you bring it together it is so magical.

I notice in ‘Confessions …’ slight glimpses of men: we see a slowed down sequence of a man walking towards, and then, behind a curtain. And an image of a man’s arm that looks as though it’s dragging on the floor.

The arm is from ‘The Great Gatsby’. Of course I am a feminist and I am interested in how female characters are being portrayed. There is a certain vocabulary and a certain imagery when it comes to representations of women. Perhaps later, in 20 years, I will explore a vocabulary about men. Mostly films are made by men. It’s just a fact. So the view is automatically a male view.

Perhaps with looking at the past, distance and time gives you a way of seeing that is more critical than when you exist in close proximity to something. Is there something interesting for you about time?

I think there is nothing objective about time, and I do think there is nothing objective about the past or about memory. I am very interested in these things. When you remember something you are sure of your memory, but someone else who experienced the same thing will have a different memory. The timing, and pacing of memories are so different.

In film you seem to be very interested in interiors, in space, in the affects, and emotions, that space produces?

Yes, absolutely. It’s about proportion, and about perspective, and where you decide to put the camera? How you cut, and what you cut first. You decide where you put the camera, and how you’re going to do the telling.

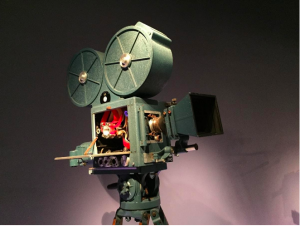

How did you get to the sculpture?

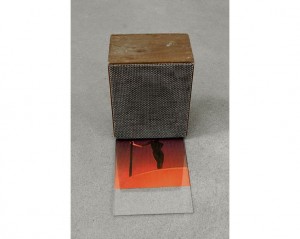

I think video for me has a sculptural aspect. I came to these objects from collage. Through the process of collage, I started to think about work that is three dimensional.

What is the process that drives the object-based works?

I work with collage, with assemblage, with materials and objects I find. But somehow it is difficult for me to make a drawing about what I want the work to be because I go from the material. That is a very formal approach. You can say it’s just about the formal aspect of the work, or just about the beauty of the thing, or about the material. But it is also about an internal drive that is propelled by a theme that is moving me. The titles of the pieces are key for me. It’s not that they should simply describe the work (tell us what it is about). They are abstract but they drive me through the work. The title of the show is ‘Awkward Studies’ and I do think works are never really finished. I see everything as a study. There is also an awkwardness to the material combinations.

Is there something about space that interests you in the making of the three-dimensional work?

Yes. Each time I would work with paper I would try to add material that is three-dimensional. I would add and add, and it wouldn’t work. The only thing that would work was to take the two-dimensional aspect out of it, and it was there. I think about the work in a relationship to the spaces they inhabit, and the juxtapositions of objects.

Is there a narrative that drives the object based works, or is the process of making them more organic?

I think it is something more organic but then again story-telling is something that comes from the gut, and a story is something you want to tell or you don’t. And it doesn’t mean that someone wants to listen.