Self-flagellator …Landy in his National Gallery studio, wearing the arm of St Jerome. Photograph: Sarah Lee for the Guardian

Michael Landy is a peculiar choice as resident artist of the National Gallery in London: until he was offered the two-year role, he’d never been. “This is like confessing,” he says guiltily. “But I was too busy at church.” He’s joking – but, coming from a family of east London Irish Catholics, there is a tiny bit of truth in this. As a kid, adds the artist, he was a regular at the Tate and the Saatchi – more interested in the new than the old.

And unlike the last resident artist, Alison Watt, the Scot who made graceful paintings inspired by the folds of fabric depicted in the National’s Old Masters, Landy has what you might call an irreverent attitude to objects. In 2001, he made Break Down, in which he destroyed his material possessions – all 7,227 of them – including a number of artworks. In 2010, he made Art Bin: a giant tip at the South London Gallery, where artists were invited to dump their failures. You might well ask: is it safe to let this man loose on the nation’s masterpieces?

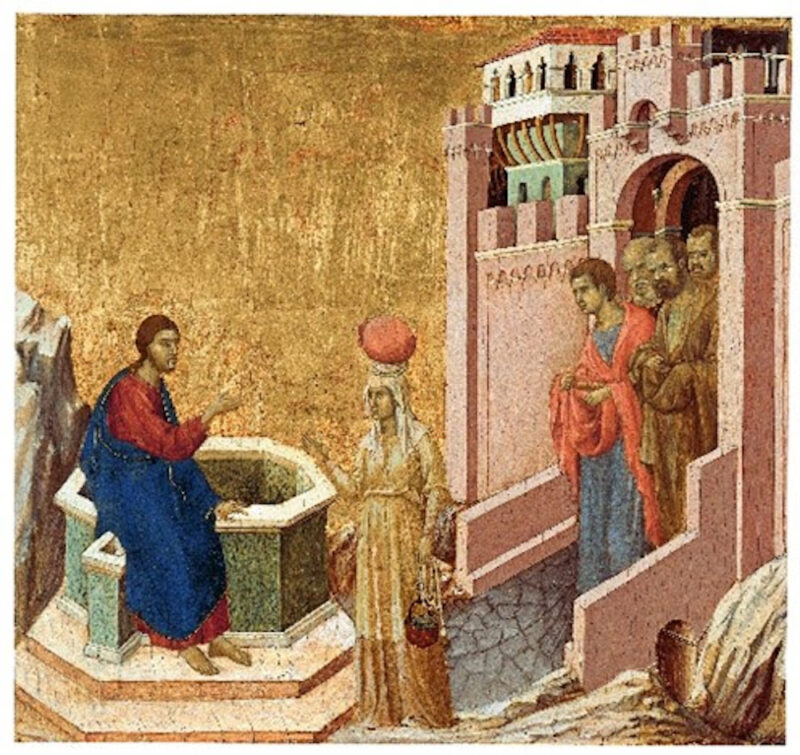

In the end – and here we come back to Landy’s religious upbringing – what really got him going, after months of looking intently at the collection and “flagellating myself”, was the depiction of saints in the collection’s medieval and Renaissance works. “They are such single-minded characters. I like the stories and their attributes.” By this, he means the fact that St Catherine can be recognised by the wheel she carries, St Lucy by a pair of eyes in a dish, St Peter Martyr by the knife slashing through his skull – all references to violent deaths the saints met. He relishes the more bizarre aspects of such tales: St Jerome, “an old man who beats his chest with a rock and has sexual hallucinations”; St Benedict, “rolling around in the snow to try and take his mind off sexual thoughts”; St Catherine, who “gets her head chopped off and milk flows from her body” (after the wheel fails to kill her).

As he says: “There are nice stories about saints – like St Nicholas, who dropped gold down people’s chimneys so their daughters wouldn’t have to become prostitutes.” But he didn’t use them. As so often with Landy, it’s all about destruction. Or rather, about the state of flux between an object’s construction, use, failure and ruin.

Which is why we are standing in a huge workshop in south London – the HQ of MDM Props, a low-profile firm that fabricates all those works that artists don’t have the means to create with their own hands: Marc Quinn’s Blood Head, the Chapman brothers’ Hell, Elmgreen and Dragset’s rocking-horse sculpture for the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square. (Nigel Schofield, the firm’s director, tells me he can stand in the middle of Frieze art fair, look around at the sculptures, and say: “We built that one and that one and that one …” Plus, MDM build all the stands.)

Here, Landy is presiding over the creation of vast kinetic sculptures inspired by the museum’s paintings, due to go on view at the National in May. One is based on a Cima da Conegliano painting of St Thomas, the doubter. “Is it safe to switch it on?” he asks Schofield. As soon as he does, a huge finger stabs Christ’s chest with surprising force. “Like a punchbag,” Landy says. St Thomas’s prodding finger is already ruining Christ’s fresh paintwork. Which is the point, says Landy: these are sculptures that in the end will destroy themselves.

He remembers going to a 1982 exhibition of kinetic sculptures at the Tate by the 20th-century Swiss artist Jean Tinguely. “It was the first time I ever saw people laugh in a gallery – and actually interact with the sculpture, by putting their foot on a pedal. Or else they had broken down; he was a rubbish engineer. They were made out of junk. I loved them.” This is his Tinguely homage.

In another part of the workshop, a painter is diligently applying colour to a figure’s face, using a reproduction of one of the National’s Cranachs as a reference. This is St Apollonia, from a double portrait of her with St Genevieve. St Apollonia was tortured by having her teeth pulled out (she is, inevitably, the patron saint of dentistry), so is pictured with a pair of pincers. When the sculpture is working, she’ll be hitting herself on the lips with a pair of tongs, ruining the careful paintwork. In another corner, there’s a vast Catherine wheel that visitors will be able to spin. When it stops, it will give you a sort of fortune-cookie reading, drawn from elements of the saint’s life: “You will remain a virgin for the rest of your life”; “You will have a mystic marriage with the Christ Child”.

Elsewhere, a “multisaint” is being built: a mad, mangled Frankenstein’s monster of a sculpture with body parts harvested from different saints. The top part is St Peter Martyr, from a Carlo Crivelli altarpiece, with a cleaver through his head, as nonchalant as if he was “having a chat about what time the No 36 bus is coming”. This sculpture will be 4m tall, with St Michael’s legs and a red, glowing griddle for St Lawrence, the patron saint of chefs, who was chargrilled to death. St Lawrence had a sense of humour, points out Landy. “Halfway through, he said: ‘I’m done on this side, turn me over.'”

We travel across London to inspect his studio in the National, through the tight security of its entrance and down into the bowels of the museum. He normally works (as you might expect from someone who radically decluttered in 2001) in a bare, office-like space. His setup at the gallery is different: the walls are lined with the drawings and collages he has made from reproductions of the paintings. Some are like 2D versions of the “multisaint”, with body parts from different works stuck together. One is a torso of St Sebastian, who was pierced with arrows; in Landy’s version, his body becomes “like a pincushion”, bristling with every arrow Landy found in paintings of the saint.

“Chopping things up, that’s what I’m doing,” he says. “A bit from here, a bit from there. I’m creating my own saints: taking the body parts. That’s why the exhibition is called Saints Alive. I’m resurrecting” – he stops himself – “reanimating them”. Landy chucks any unneeded shreds of paper on to the floor, which now crunches with them. Postcards and reproductions are stuck to the walls, and there’s an image of the Rokeby Venus, from a photograph taken after the canvas was slashed by a suffragette in 1914. There’s also a copy of Hall’s Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art.

How will these huge kinetic sculptures go down in the normally quiet, studious rooms of the National? “Like a lead balloon?” he laughs. “I like to think younger, hipper people will like it. The older people – they’re all deaf anyway. I don’t want to, or mean to, offend religious people. It’s just my take on the saints. One could think it’s slightly absurd, boiling people in urine or pulling out their bowels using winches.” He laughs nervously. “For this exhibition, I am going to be martyred.”

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.