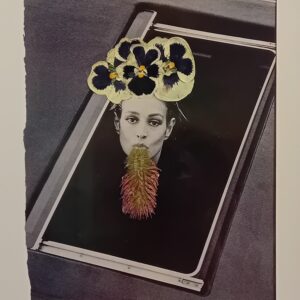

Inside out … Rachel Whiteread’s Detached 3 (2012). Photograph: Mike Bruce/Copyright Rachel Whiteread/Courtesy Gagosian Gallery

It is almost exactly 20 years since Rachel Whiteread received official approval from a fractious coalition of councillors and residents in east London to create what still remains her best-known artwork, House. By the spring of 1993 there had already been two years of preparation for the project. Work eventually began that summer on the last remaining property in a demolished terrace on Grove Road, Bow.

Liquid concrete – the same product that is used to patch up the white cliffs of Dover – was sprayed on to the house’s interior to create a cast, and then the external walls were carefully removed. The work was finally finished in late autumn, revealing a full-sized, inverse representation of the three-storey home, complete with outlines of fireplaces, windows, architraves and staircases. Less than a month after its official opening, Whiteread, aged just 30, was awarded the Turner prize.

The work was Whiteread’s most ambitious exploration to date of the utterly familiar, yet almost entirely overlooked. And within the apparently blank concrete surface were exposed the affecting remnants of lives lived. Whiteread found herself being thanked by two former residents of the demolished terrace for “making their memories real”.

“People still talk to me a lot about House,” she says today. “It still seems to be incredibly evocative and people can bring it up in their mind’s eye. That’s obviously very pleasing, but I also know that part of it is undoubtedly to do with the way it was destroyed.”

For all the praise House attracted, it was also a lightning conductor for varying degrees of opportunistic political and artistic objection. Unofficial laureate of east London Iain Sinclair captured well the “freakish alliance of extremes” that eventually coalesced in opposition: “Come in the K Foundation, Brian Sewell, Stewart Home, Councillor Eric Flounders. Come in Class War, the BNP, and the M11 protest lobby.” On the very day of the Turner prize announcement, a sub-committee of the local authority made the decision that the lease should not be renewed, and so in January 1994, less than four months after its completion, House was demolished.

Whiteread’s early career was associated with the Young British Artists generation. “YBAs? OBAs?” she laughs. “What is the correct term these days?” (Like Tracey Emin and several other YBAs, Whiteread is 50 this year). And over the last 20 years she has put together a body of work that includes the Holocaust memorial in the Judenplatz in Vienna, the fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square, filling the Turbine Hall of Tate Modern with 14,000 plastic boxes and providing a new frieze on the façade of the Whitechapel Gallery. Her latest work will be exhibited at the Gagosian Gallery in London later this week. The show is called Detached and features casts of secondhand sheds, doors and windows, as well as smaller casts and works on paper.

Back in 2002, speaking about House, Whiteread declared it was a shame the work “didn’t have the chance to become invisible, the way architecture becomes invisible. I think that’s an interesting idea and maybe it’s something that I will work with at some point.” The sheds in Detached could be seen as her addressing that idea. “I call them ‘shy sculptures’,” she says. “The first one I made was of a boathouse on a fjord in Norway. It’s had hardly any attention, and I really wanted to make things that you just come across, very much a part of the landscape.” She’s also making a piece that will go into a wood in Norfolk, and one for a desert in America. “House disappeared, but these things will just be there in the landscape.”

Alongside the large sheds will be smaller objects, “items put together that might include a found old can, a new cast of an old can, and something that might be called sculpture.” Her large east London studio – and home she shares with husband and fellow sculptor Marcus Taylor and their two sons – is full of disparate objects she has found or made. “My show of drawings at the Tate a few years ago made me think of all these things I’d collected since I was a kid. I’ve called them ‘abject objects’, and I’ve just sort of played with them, applying silver leaf or casting in ferrous plaster so that they rust or patinate.”

She says that physically playing with these objects helps her to work things out. “They are almost like doodles. It’s what I’ve always done. When I was a kid my friends would be obsessed by music and would learn every lyric of songs, but I was never into that. I was totally interested in the physical world and would always be making something, playing around with bits and pieces I’d found, changing them from one thing into another.”

Whiteread was born in 1963, the youngest of three girls with her elder sisters being identical twins. Their mother was an artist and their father a teacher, lecturer and educational administrator. The family lived in rural Essex until moving to London when Whiteread was seven, where she remembers a house full of politics and art. Not only would she go canvassing with her father for the Labour party, there’d be trips to the National Gallery, “and also to wacky 70s happenings at the Roundhouse. We went to lots of interesting things and my mother was involved in a famous feminist exhibition at the ICA called Women’s Images of Men. I remember it being put together in our basement in Muswell Hill, and so I’ve known people like Iwona Blazwick and Sandy Nairne [who both worked at the ICA early in their careers and are now directors of the Whitechapel Gallery and the National Portrait Gallery respectively] since I was 13.”

She says she did go through a brief period of rebelling against her mother “and claiming that I wanted nothing to do with art. But by the time I was in the sixth form I was pretty committed.” As a child, Whiteread’s two favourite images – printed on postcards she still has – were of Bridget Riley op art and Anthony Caro’s groundbreaking 1962 sculpture Early One Morning. Although she never thought of herself as the best painter in her school, she was aware of having “a hyperactive mind and seeing a lot of possibilities. By the time I went on a foundation course I was desperate to start making work.”

Despite enrolling on the BA painting course at Brighton Polytechnic, she spent most of her time in the sculpture department. In her second year the artist Richard Wilson gave a workshop on casting and, importantly for the rest of her career, Whiteread saw for the first time that the cast of the space around a simple spoon resulted in it “simultaneously both losing and retaining elements of its essential ‘spoon-ness’. I can’t say that I realised there and then that the possibilities might be almost endless, but I knew it was challenging and interesting that something so simple could change your perception of objects.”

It was while on the Sculpture MA at the Slade from 1985–87 that Whiteread made her first discernibly Whitereadean piece of sculpture, Closet, a black felt-covered plaster cast of the inside of a cupboard. The impulse for the apparently blank and stark piece was both emotional and nostalgic in that it conjured for her the – comforting, she insists – childhood memories of hiding in a dark cupboard. It was followed by another work prompted by personal experience: Shallow Breath, a cast of the space underneath a bed, has often been described as reminiscent of a rib cage, and was made not long after her father died.

By then she was renting a studio “funded by Thatcher’s dream, the Enterprise Allowance Scheme. It was a massage of the unemployment figures and I know an awful lot of people who went on it. You got 40 quid a week but you could do anything. So I was an artist, but also a painter and decorator, a prop maker, a film person. I had a studio with no windows and lots of mice. It was where the Olympics site is now, and there were a lot of artists there” – Grayson Perry’s studio was close by – “so we would visit each other’s studios a lot and people were generally supportive of each other.”

Both Closet and Shallow Breath featured in her first important solo show at a tiny Islington gallery in 1988. “It was basically a very small domestic space, and I showed the cast of the inside of a dressing table, the underside of a bed, the inside of a wardrobe and a hot water bottle. I thought they were all elements that you might have in a room like that, filled with postwar utilitarian furniture.”

The pieces all sold and Whiteread was able to attract funding for her most ambitious project to date, Ghost (1990), that saw her shortlisted for the Turner prize. It was a cast of a room in a house in Archway, north London, that was put together with a “great deal of second-hand dexion, plaster, rubber, wood and a lot of hard work.” The work has passed through several collectors since then, including Charles Saatchi, and is now in the National Gallery of Art in Washington. In an unusual validation of her belief that spaces retain human history, she was recently told by a visitor to the museum that the room must have been part of a house occupied by relatives of Rod Stewart. “Apparently the fireplace had been installed by this guy’s father.”

By 1992 Whiteread had featured in Saatchi’s Young British Art shows alongside the likes of Sarah Lucas and Damien Hirst. She also showed work in the definitive YBA exhibitions Sensation and Brilliant. How did she react to her friends and contemporaries becoming as famous as pop stars? “Some people have made it their mission to become extremely well-known. For Tracey [Emin] it is part of her work. I’m nothing like that and neither are most of my contemporaries. People like Gary [Hume] or Sarah [Lucas] muddle along and get on with their work and do a bit of publicity when they have a show.”

She says she went into a career in art knowing what was ahead of her. “My mum was an artist so I was aware that being a committed artist didn’t mean you would earn any money. As it turned out I have earned quite a lot of money and that’s been great. But I didn’t expect it, unlike a lot of my contemporaries during the heady early days of YBAs when money was quite an important part of it all. I was ambitious for my work, but I always thought I would fund it through teaching, and that’s what I did for five years.”

She says she enjoyed teaching but eventually gave it up when too many students “wanted to know how to become a wealthy artist. It wasn’t really about making work any more, it was about having a big career. I just kept saying ‘keep your head down and get on with it’. If the work is good enough the career will come.”

Whiteread’s own career certainly came with House and the Turner prize, although she found the process uncomfortable. “I’d made House and I was something of a physical and nervous wreck. Then, on the day of the Turner, the council said they were going to pull it down and there was also the crazy K Foundation thing.” Art pranksters the K Foundation awarded Whiteread their worst artist of the year award and “blackmailed” her into accepting the £40,000 prize – twice the money of the Turner prize – by threatening to burn the cash if she refused. In the end, she gave away the bulk of it to homelessness charity Shelter and in grants to young artists. “So the whole thing was too much stress really, and looking back it is a bit of a blur.”

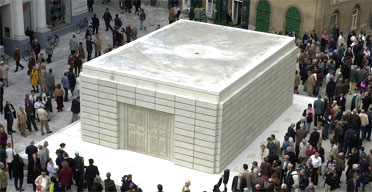

Her next major commission, the Vienna Holocaust memorial, was an equally fraught process due to the complications of Austrian politics and the inevitable sensitivities around the issue. It took over five years to complete, but while she now says she wouldn’t go through that sort of process again, she is very proud of the work, a large concrete cast of a library with the titles of the books facing inwards. “The politics were horrendous, but I’m happy at the way people seem to respect the piece and to use it as a place to think about what happened.”

She now takes on very few commissions, but was keen to make a new frieze for the Whitechapel gallery despite the problems of negotiating with English Heritage “about what you can and can’t do. Having to stick to your guns is kind of exhausting. But as I’ve lived round here forever it was very nice to be asked, and it did feel as if I was giving something back.

“What I’m not into is what I call ‘plop’ art. Making things and just putting them in places for the sake of it. I don’t like much sculpture in the street. It really needs a reason for being there, but when it does, it can be a wonderful thing. I don’t think art changes the world in terms of stopping people dying of Aids or of starvation or being homeless. But for an individual, seeing a great piece of art can take you from one place to another – it can enhance daily life, reflect our times and, in that sense, change the way you think and are.”

Her forthcoming schedule – “I’m booked until 2018” – includes large-scale works as well as making a special edition of a book to accompany the New York stage version of Colm Tóibín’s novella The Testament of Mary. Small art remains as important to her as her large projects. “I changed my way of working a few years ago in that I used to have lots of assistants and then realised that wasn’t for me. A lot of the early work was based on my size and what I could lift. I still bring in people to help me when needed, but I love doing the smaller things myself and I try to keep my touch on the work. It goes back to the beginning.”

There is a print in the new show of a squashed can she found on her first day as an undergraduate, and she still uses college sketchbooks.

“I’m always recycling in my head. It can take a long time to develop your vocabulary as an artist, but now I’m coming up to be half a century I suppose I should be getting there. Then again, my mum always said that I had an old soul, and I do now feel as if I’ve finally grown into my age.”

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.