What is Bernadette Corporation? A group of artists? Definitely. And writers? Sort of. Fashion designers? Once. Party promoters? If you know the right people. Anarchists? Probably not. The anonymous, endlessly mutating New York collective relies on rumour, subterfuge, fictional characters and avatars. Nothing is certain.

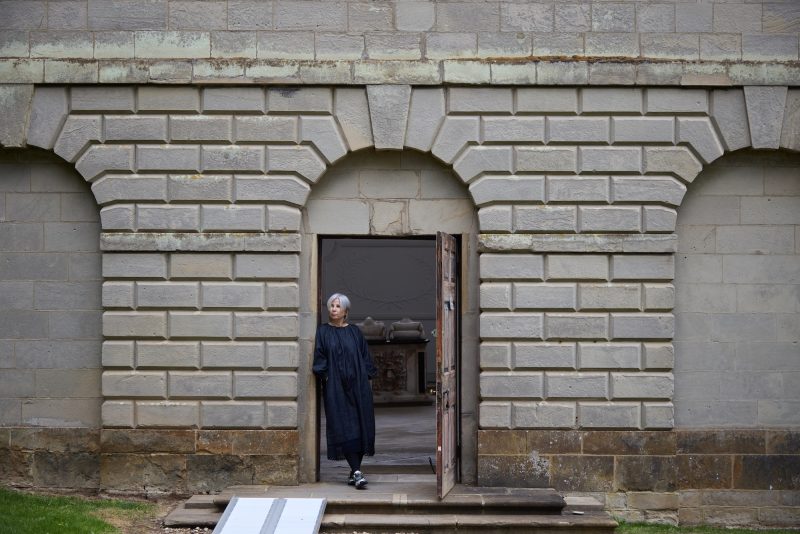

“We have a corporate front, but behind the logo it’s total chaos,” says John Kelsey when I meet him and Bernadette Van-Huy, two of BC’s core members, in New York. The collective – whose first British retrospective, called 2000 Wasted Years, is about to open at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts – came together in 1994, when Van-Huy had just finished an economics degree, and New York nightlife beckoned. “I had barely been to a club and then, randomly, got asked to host a night. So I put together a group of people, and they elected the name Bernadette Corporation. We did it for one summer. Then they fired us.”

What began as a disco night soon changed into something more enduring: a fashion label that developed a cult following. The Bernadette Corporation label was to some degree an attack on, or parody of, high fashion. Catwalk shows featured mascots in bear costumes and, once, a group of cheerleaders. Although the label set out to expose the fashion industry’s appropriation of downtown (often immigrant) subcultures, it was also a bona fide brand, covered everywhere from i-D magazine to the New York Times, and noted for recklessly mixing high and low end looks in single items. The ICA show includes several outfits, draped over slouchy mannequins; visiting the show’s earlier incarnation in New York felt a bit like attending some hip party in the days of Clinton’s presidency.

Why did they call themselves a corporation? “I think it was just a way to annoy people,” Van-Huy says. “It was an anti-art stance, to embrace this kind of crass commercialism. Doing something in a gallery seemed so rarefied and serious. Exclusive, too. We just preferred to speak in a common language and in a form that was more stupid.”

Soon, BC launched its own magazine, Made in USA, which placed essays by French philosophers alongside features about H&M. “We just did it in the apartment all by ourselves,” Kelsey says. “We had to hustle ads from art-gallery friends. We had the idea to do a fashion magazine that was dysfunctional in regard to fashion, something with a real DIY, anti-skill ethic.”

BC had no patience with the idea that artists could drop out of the capitalist system, punk-style, or resist it from some imagined outside position like 1960s hippies. They called on young creative types to give up their fantasies of artistic autonomy, band together, and commit to working inside economic networks. “Don’t have sex with each other,” they warned. “Above all, don’t romanticise the communal life – dress for work every day, keep regular business hours, and learn proper phone manners.”

Then two events changed BC. First was the massive antiglobalisation protest during the 2001 G8 meeting in Genoa; the second, six weeks later, was 9/11. “Our attention shifted,” Kelsey says. “Fashion became very guilty somehow.” Van-Huy agrees: “It was difficult to return. It wasn’t that the magazine was no longer financially viable, because it was barely financially viable to begin with. But there was sort of a break that was irrevocable.”

Reading this on mobile? Click here to view video

The attacks inspired one of BC’s most influential and inflammatory works, the “anti-documentary” Get Rid of Yourself. Opening with an image of the smoking towers, it combines footage of “black bloc” protestors (anarchists who disrupt non-violent demos with vandalism and arson) with sequences in which Chloë Sevigny, actor and muse to New York’s downtown fashion set, mumbles revolutionary slogans in a sundress. Sample line: “The best Molotov cocktails are made with a mix of gas and acid. They burn better and cause more damage to cops.” While other artists might have feared accusations of “radical chic”, BC encouraged them – as if to say that all left activism had become so ineffectual that all one could do is make a fashion statement.

Yet the more enduring work from that period is Reena Spaulings, a novel “written by” BC, but in fact the product of over 150 anonymous contributors. A meandering tale of post-9/11 New York, Reena Spaulings follows its fictional title character, a museum guard turned supermodel, everywhere from the Metropolitan Museum of Art to a banging fashion party. “There wasn’t ever the idea of writing a skilful novel,” Kelsey says. “We asked non-writers and non-English speakers to contribute. A group of us worked on it constantly, kind of like an editorial board, and we gave precise instructions: give us dialogue for two characters in an elevator; describe the scene backstage at a Strokes concert in Central Park.” The novel was published in 2004, and Reena has enjoyed a substantial real-world afterlife: “she” now directs a successful art gallery (in fact partly run by Kelsey) and even has a work in MoMA’s permanent collection.

BC never anticipated having a retrospective. “We’re not that old,” says Van-Huy. Sceptical of the tendency in today’s art world to solidify the recent past, the artists have rejigged many of their earlier works, hiring a film-maker to re-edit Get Rid of Yourself into what Kelsey calls “a snappy, trashy trailer”, all pumping music and explosions. Fashion campaigns from the 1990s are reworked into slick digital presentations, and many of BC’s past actions and products have been turned into a timeline that takes up a full gallery.

“There’s a real fetishisation of the 90s right now,” Kelsey says, pointing specifically to a current show in New York called NYC 1993, which looks nostalgically at recent art. “When I talk to younger people, there’s this thing I always hear, that they missed out on ‘authentic’ New York somehow. But I don’t think New York was more authentic then. Our retrospective fucks with that expectation of coming and finding something authentic – because everything in the show is new.”

Since BC couldn’t care less about the dividing line between original and copy, real and fake, they prefer to think of the show as a reboot: a chance both to continue and start again. “It’s kind of liberating,” Van-Huy says of the show, which has made her feel “a lot more mature – like an adult. It changed my life. I behave very differently.”

“The retrospective changed your life?” says Kelsey, looking askance.

“Yeah!”

“It didn’t change mine at all.”

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.