Yvette Greslé caught up with David Blandy (and his father, John Blandy) at an exhibition of new work at Seventeen gallery. Blandy invited his father, John, to collaborate with him on a project that thinks about different kinds of dialogue (in times and places both actual and virtual). Creative dialogues between father and son have begun to emerge in documentary form. I think here of film-maker Tomas Koolhaas’ current project: a feature length documentary film about his father the architect Rem Koolhaas. Or the documentary ‘My Architect’: Nathaniel Kahn’s personal journey into the life and work of his late father Louis Kahn (again an architect). The Blandy conversation is based on a father/son relationship but it is also about two artists (and the choices that they have made at different times and places in their lives). Rather then a documentary account, their relationship is figured through the making of work that emerges out of a process of conversation and creative collaboration.

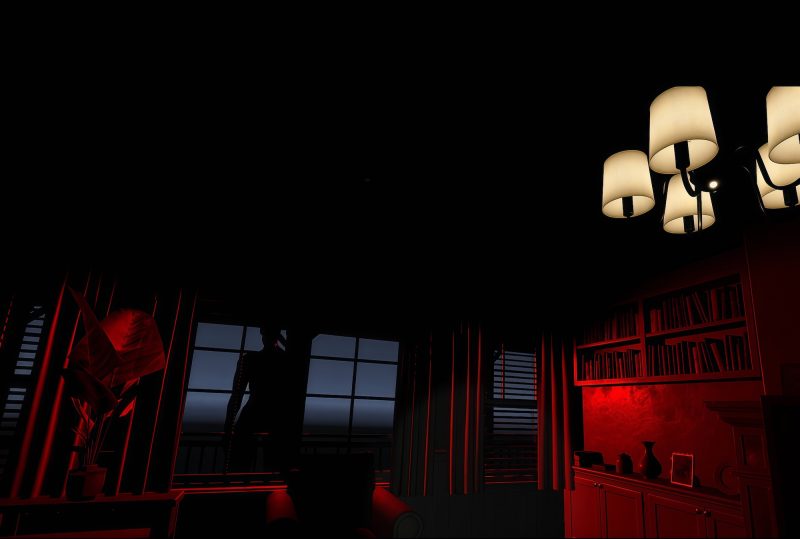

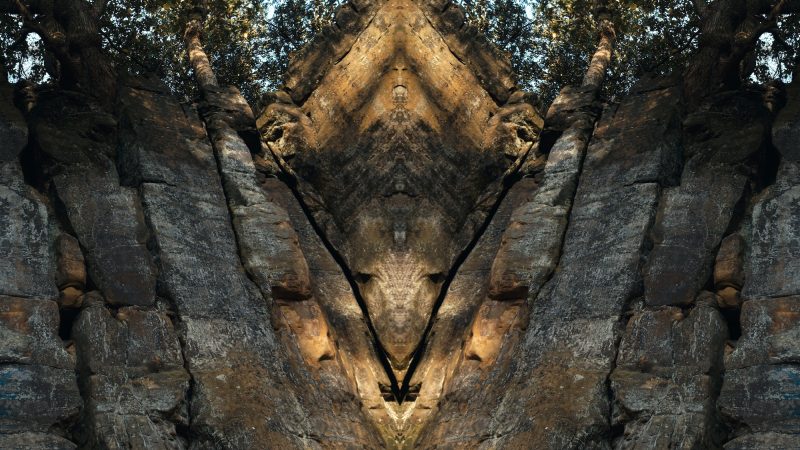

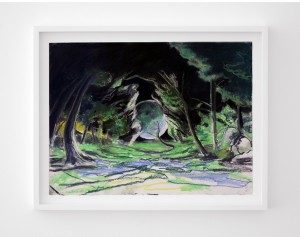

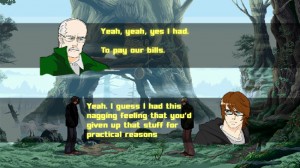

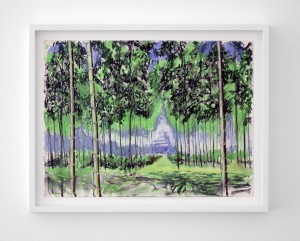

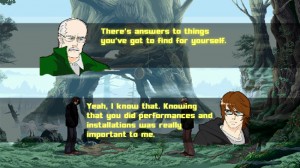

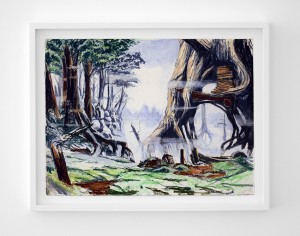

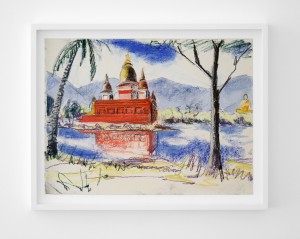

David Blandy’s digital landscape rests, in a corner (and on the floor). We look downwards and watch as two figures, father and son, walk and converse (text boxes transmit a dialogue). Seasons and landscapes shift and transform as we look. We observe pixelated surfaces and otherworldly colours (sometimes intense and saturated, and at other times bleak). Music (punctuated by silences) travels through the gallery space affecting us as we observe, not only the images that move across the screen-surface, but also the landscapes that hang on the walls around us. John Blandy’s pastel drawings, are a different kind of language: they bring together the processes of hand-drawn marks on paper and landscapes, that we imagine, both reference and precede the virtual realities we inhabit today. Their scale is intimate, as is the immediacy of marks, lines and textures on a paper surface.

The exhibition doesn’t overly define the relationship between father and son, or the spaces they inhabit (creative and personal; actual and virtual): it is a quiet and affecting exploration of different creative processes and internal lives, and a relationship that remains private even as it is staged for our view. As the conversation between father and son tells us, choosing to be an artist (and a certain kind of artist) in a world so over-determined by commercial imperatives, brings with it particular kinds of challenges, and constraints. Exhibition runs through 23 March 2013 www.seventeengallery.com.

Conversation with David Blandy

What is the background to the show? What motivated you to make this work, and collaborate with your father?

It was a way of starting to have a conversation with my father about art, and about where I’ve come from, and where he’s come from. And how his life and career has affected how I’ve thought about art and where I wanted to go with it. I asked him to draw backgrounds from computer games that I gave him. I showed him pictures of games that I really enjoyed as a young adult and I just wanted him to have an insight into my universe. I gave him a series of images that I thought he might be interested in. He went through them and chose ones that he thought would made sense for how he draws. He always draws from life so to be confronted by a still image of what is effectively another artist’s work was a bit of a stretch: but he really started to understand the spaces and interpret them. I didn’t want to be too prescriptive. A lot of the ones that ended up being up in the exhibition were not necessarily the ones that I’d have chosen.

It’s interesting that you draw here on the idea of a father/son relationship, which is also a relationship between two artists, and two generations.

I’ve always been frustrated that my dad’s work isn’t more appreciated. At the same time I’ve never been quite sure of his reaction to my work because we don’t really talk about it. I started to make assumptions that he didn’t like certain things that I was doing. My use of collage and so on is very different from his idea of mark-making.

What does he produce as an artist?

His main project has been drawing the same tree, almost every day for years. He’s produced 2 500 of drawings of the same tree, from the same perspective. So, as you go through them, you get changes of seasons, and times of day.

How did you construct this work? How do you put it together? Is each frame a composite?

It’s a mixture of composites. So for the backgrounds in the video I took existing fan-made GIFs (which themselves have been fabricated by extracting all the separate image elements out of the original game file). The background in a 2D fighting game is rarely one solid image: the programmers use separate layers to generate “parallax scrolling”. This creates the illusion of depth, and animated elements to give the scene life. The fan-made GIFs combine these elements into a single animation cycle from a single point of view.

The sprites that I created for my father and me are what are known in the Mugen community as Frankensprites. You have an existing sprite (low resolution 2D image) and add it to part of another to create a new character or animation. The sprites for “Backgrounds” are based on K’ [pronounced K- dash] from SNK’s King of Fighters 99. And then I’ve changed the top-half of him, and changed the colours etc. So now I’ve got a walking animation that is turned into me and my father: through a bit of pixel art. And the final layer is that there’s a composite of different sound effects from different games to create the atmosphere and the music.

The experience of watching the piece is very affecting: the way the images capture movement, time passing, and the changes in weather (the music adds to this). Where is the music from?

The music is a piece of incidental chip-music in a game by SNK called Last Blade, which occurs after you have a confrontation with a significant character in the plotline, before going on to your next battle.

How did you stage the conversation between you and your father?

The conversation is effectively a transcript. I did edit it, from a recording. Originally I had it completely verbatim but it’s just too long. I got it down to its essentials, which is what happens in fighter games. In fighting games, characters don’t have a whole conversation, and I was trying to follow that mode. I’m also referencing games like Final Fantasy VII where you’ll have really intense existential conversations. You’re talking about life and death and the universe. It becomes oddly emotional (even in the games).

What is the importance of place in your work?

That’s often the starting point. With ‘Child of the Atom’ it was Hiroshima and my emotional relationship with that place. Sometimes it’s a conceptual place and sometimes it’s a real place, or location. It’s also the imagined place of the background of these games. Sometimes you come out of the activity of the fight and you start to appreciate the space that you’re in. I’ve always been interested by the emotional register of fighting games.

Conversation with John Blandy

What was this project with David like for you?

I’ve worked on other things with him before: the conversation between Darth Vader and Sky Walker (we did a lip synch together). I used to watch him playing computer games and all that sort of stuff, and I remember the games he plays while making work. In making the work for this show, I searched through images and selected the ones that spoke to me. I used the images as a base: my drawings are not completely accurate, but they’re not inaccurate. I get the essence of the backgrounds but make them into a landscape that I can believe in. I’m fairly instinctual in the way I make work.

You’re a landscape artist? Place comes up a lot in David’s work.

I used to be an artist who was sent by a gallery to travel around the world and paint landscapes. These paintings were based on my feelings and responses to landscape. David remembers me going off travelling when he was a kid. I also used to take him out drawing, into the countryside.

David mentioned that you’ve made hundreds of drawings of a single tree?

There’s a tree that I’ve been painting for the last 15 years. It’s a lime tree in Queen’s Park (North West London). But it doesn’t really matter to me what kind of tree it is. It’s a kind of riposte to the idea that you can go around the world painting different landscapes. Different landscapes can come to you standing in one spot. It’s a response to people just going off to work and coming back again. It’s also a way of keeping yourself in hand with what you can do, with your practice.

Before the landscapes you were making different kinds of work (conceptual work). It’s interesting in David’s work, the conversation you have as artists as well as father and son. You draw attention to the choices that artists make and the struggles that inform these.

I used to make things like drips of water on a hot plate. Or standing in a white plastic cube: flinging paint around, and slowing obliterating the surface so that you become invisible inside. That was in the 60s, 70s and 80s.