Reading on a mobile? Watch video here

Animal parts, flayed hounds and chopped-up deer turn on Bruce Nauman‘s carousel in endless chase. Not bounding, but suspended from slowly turning beams. Some hang like things in a butcher’s window, others drag along the floor. The bodies are based on the casts used in taxidermy, later to be clothed in skin. They’re like life, but not life. The scene is morbid. What goes around comes around, dead presences wearily rotating.

Carousel (Stainless steel version), from 1988, is one of five works by Nauman occupying a single gallery at Hauser & Wirth on London’s Savile Row. Over the years I have encountered a lot of Nauman’s work – even some of those displayed here, some of which exist in several versions. But every time is different. You can still be left speechless and empty-headed in front of someone’s art, however well prepared you think you are.

The exhibition, and the accompanying book by the curator Philip Larratt-Smith, is called Mindfuck. This is brutal, and in both the choice and juxtaposition of works (all loans from various places) and Larratt-Smith’s text, he opts to emphasise the traumatic in Nauman – though it is always unavoidable. Larratt-Smith reads Nauman in the light of psychoanalysis, just as he did in the exhibition he curated of Louise Bourgeois at the Freud Museum last year. He has also edited Bourgeois’s notes about her own analysis.

But you don’t need to be a student of Freud, or even have a close acquaintance with Nauman’s work, to grasp that his art plumbs extreme mental states. Hilarity and abjection, humiliation and futility, aggression and a feeling of windedness are all on the surface. They don’t need much digging for.

I sidle down an ever-narrowing corridor towards an open doorway and slip into an empty white room. Except it is not quite white, but lit by harsh, pale green striplights. The light fills the empty parallelogram of the room with an unpleasant sickly pallor. I stare at my hands and they look suddenly horrible, mottled and half-dead. Goodness knows what it does to my face. It feels like an antechamber to a morgue in here, which I guess is the point. I feel exposed. Nakedness in here would not be appealing. All that effort to get there, and now all that’s left is to leave, edging out as quick as I can through another narrow exit.

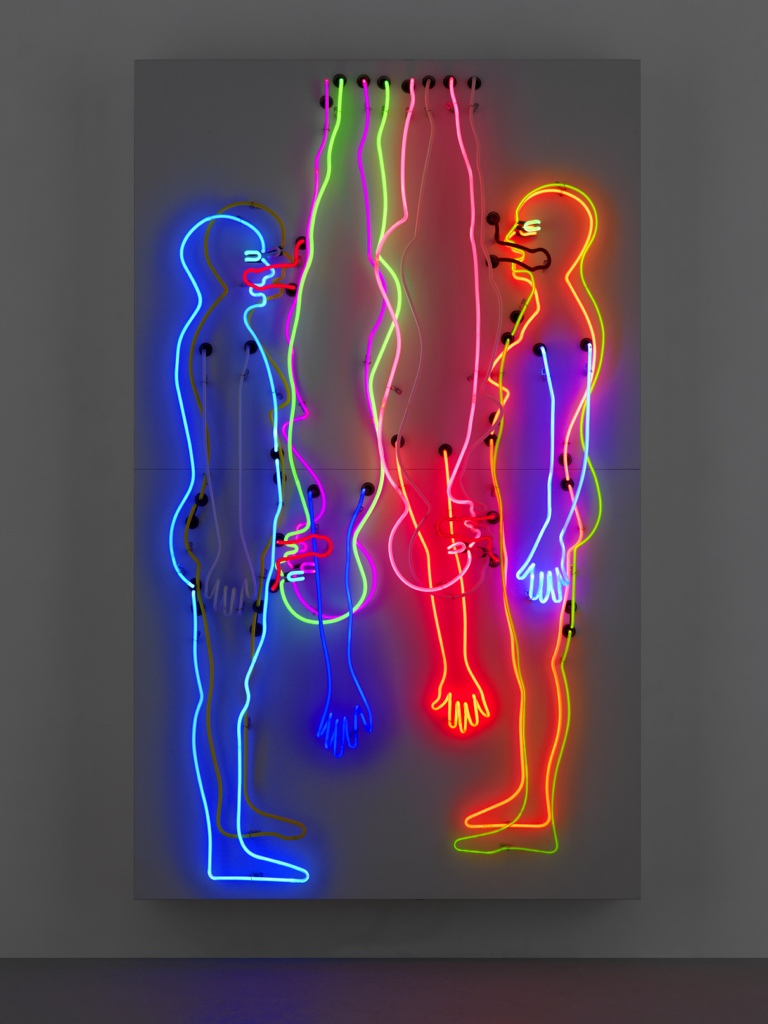

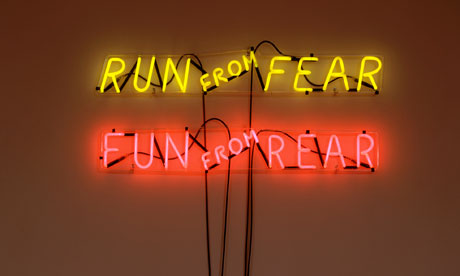

More naked bodies in coloured neon outlines pulse on the wall. As the lights flick on and off, the figures change from male to female and back again. Genders keep flipping back and forth, bodies entangled, right way up and upside down, standing and hanging. All these figures are performing fellatio, in the 69 position. Mouths are open, mouths are closed. Cocks pulse red. Up close I get snared in the fluctuating images, caught up in a life-size dirty-picture neon embrace. Over on another wall, a neon sign says “Run from fear” – a bit of graffiti Nauman once saw scrawled on a bridge over a highway – and below it the words “Fun from rear”. Another reversal, another inversion. Is the sign an order, an injunction, or just a bit of wordplay? The final work in Mindfuck is a 1986-7 neon version of Good Boy, Bad Boy, whose hundred phrases Nauman made into a video, performed by a white woman and a black man, the following year. You may have heard it as a spoken sound piece in Nauman’s Raw Materials, his 2004 Turbine Hall commission. The phrases of neon text thud on and off, are highlighted and then gone. Like the carousel, there’s a sense that these flat statements are interminable roundelays of good and bad, virtue and evil, shitting and pissing and drinking and sleeping, working and playing, sex and hatred, life and death. Nauman’s text is exhausting. He has wrung everything out and still wrings some more. What’s left? What’s missing? Is this all there is?

I’m glad I am not still on the couch; this stuff could undo me. And as I look at the words on the wall, the carousel keeps turning. Yet there is something missing. Those rotating, dangling body parts were originally intended to be dragged around the concrete floor, with a terrible sound of screeching. All they make here is a quiet shush as they revolve on a floor constructed from MDF which acts as a sort of plinth. It’s less a Mindfuck, more a lullaby.

This, I was told by someone at Hauser & Wirth, is a conservation issue – the sculptures risk being worn away by their interminable circular journey – but the work’s imminent auto-destruction is, I would surmise, an intended consequence of what Nauman originally had in mind. Where the work was once aggressive, it is now muffled, pathetic. But it is impressive for all that; though it does raise serious issues about the way an artist’s intentions, and work itself, can be misrepresented – or in this case muted. I want to hear the metal scream.

What draws me to Nauman? Something more than masochism, an attraction to discomfiture: there’s nothing like a feeling of futility to get the juices going. His art can be brutal, beautiful, aggressive and arresting, and it is always surprising and rich.

In the catalogue, Larratt-Smith brings out the richness of Nauman’s works and casts them in the light of analysis, without ever closing down the way we might think about Nauman. But the best thing about the book is the pictures, which tell their own stories: these images of copulating chimps and dogs, US prison cages and behaviorist lab-rat experiments, and serial killer John Wayne Gacy dressed as a clown are all pertinent to Nauman’s art.

I doubt any artist would be neutral to this kind of framing of their work, or to a title such as Mindfuck. But Nauman’s art is complex enough to take all this freight on board – and in any case, he always screws with your head.

As it is, none of us walks into a show with empty heads: we carry much more than thoughts of art with us. It could be the residue of last night’s dream or a bill to pay, some private anxiety or something overheard that keeps going round your head. Love and hate, fear of death: the carousel keeps turning.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.