Banned … Ai Weiwei’s Grass Mud Horse Style parody of Psy’s Gangnam Style.

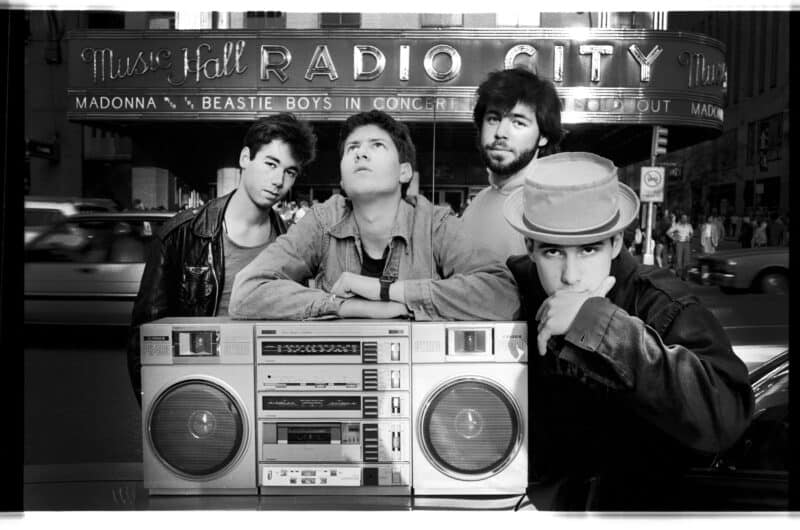

On Thursday evening, a group of artists will gather at Anish Kapoor‘s studio in London to shoot a parody of Psy’s monster hit Gangnam Style, in support of Ai Weiwei. This follows Ai’s own version last month, which featured the original video interspersed with clips of Ai and friends doing the dance. The video swept the internet, mainly thanks to the comic appeal of the eminent artist clowning around to K-pop; but the Chinese authorities scented subversion and banned it. Ai’s video was titled Grass Mud Horse Style, a reference to a Chinese profanity banned on social networking sites by the government, and at one point he is seen wearing handcuffs – presumably a reference to his detention earlier this year: he is prohibited from leaving the country. Kapoor’s hope is that his version, co-directed by the choreographer Akram Khan, and featuring dancers, actors and musicians, as well as artists, will have the same reach.

It’s not the first time a huge pop hit has been reworked to make an artistic and political statement. Since the 1960s, when Andy Warhol acted as impressario to the Velvet Underground, and when John Lennon brought Yoko Ono into the heart of the world’s biggest band, artists have attempted to hijack the mainstream and enter the rough-and-tumble arena of the charts. Thanks to their friendships with musicians, a natural desire to try their hand at other media, and an often shared art-school background, artists from Dieter Roth to Theaster Gates have added gigs and records to their oeuvres – with varying results.

Reading this on mobile? Click here to view

A few have managed hits. In 1982, Laurie Anderson stunned the art world, not to mention viewers of Top of the Pops, when she reached No 2 in the UK charts with her minimalist, vocoder-laden song O Superman. Damien Hirst reached the same peak 16 years later in rather less highbrow style, as part of Fat Les, whose Vindaloo was the unofficial England football song of 1998. Others have preferred to take the cult route. Sam Taylor-Wood has made three elegant electronic covers with Pet Shop Boys, including a take on Serge Gainsbourg’s Je t’Aime (Moi Non Plus) which features her faking an orgasm over tinkling synthesisers. Meanwhile, few people who saw them will ever forget Minty, Leigh Bowery’s musical project, which included artist Cerith Wyn Evans, and whose shows saw Bowery “give birth” to his wife, Nicola Bateman, on stage.

Even Joseph Beuys, a complex giant of 20th-century art, made a pop single, the 1982 song Sonne Statt Reagan. Beuys tunelessly barked his lyrics, which have an anti-nuclear message, over incongrously chirpy euro-rock; there is an irresistible YouTube clip of him performing it on German TV, wearing his standard uniform of jeans, a felt hat and fishing vest. It is so far removed from the rest of Beuys’s practice that many critics treat it as a strange aberration, in much the same way some sneered at Ai’s Gangnam Style. But the chances are that Beuys was trying to make a political statement that was important to him, in the most audience-friendly way he could. “It’s bizarre,” says artist David Shrigley, who has himself released several spoken-word records alongside his mordant drawings. “It makes you realise that Beuys didn’t care that much about the way people perceived him. It has a great sense of fun.”

Reading this on mobile? Click here to view

Some artists make records simply out of a wish to do something completely different. Others see it as a way of expanding their repertoire. In the 11 years since he won the Turner prize (presented, incidentally, by Madonna), Martin Creed has made records alongside his sculptures and paintings, records he describes as “one-off singles, limited-edition, homemade things”. In 1997, he released an album under the band name Owada.

Creed argues that making a record, an artwork or even giving an interview are all part of the same creative process. (He asks me for an mp3 of our interview after we speak, for possible future use.) “Working on a song to me is not much different from working on a sculpture,” he says, “in the sense that I want to make something that’s exciting, and worth looking at or listening to.” He started making music after art school, after feeling that his sculptures were failures. “When people looked at them they couldn’t see what I’d gone through – they could only see the bit left over at the end. If you’re listening to a piece of music being played, you’re listening it to it being made – the decisions to go up or down, faster or slower – so it’s more like a story.”

This year, Creed took the plunge and made an album under his own name, Love You To, co-produced by Nick McCarthy of Franz Ferdinand (an art-school graduate). Last month, Creed’s band took their clipped post-punk to the Swn music festival in Wales; they have supported the Cribs on the indie circuit, too. “I like working in different places,” says Creed. “That’s why I like doing the music. I feel the art world’s a bit of a ghetto and I don’t want to make work for a little, special society – I need to go out into the world, and that’s the way to test out work, or songs.” It bothers him if he feels that his band – a five-piece – get invited to play because of his art-world fame rather than their music; but Swn was attended by “a very music crowd”, and his album was well-reviewed.

Reading this on mobile? Click here to view

Occasionally, music can combine with art to create something truly spectacular – as Warhol and the Velvet Underground twigged when they came up with the Exploding Plastic Inevitable, which featured the band playing at ear-splitting volume, film projections, blinding strobe lights and a “whip dance” by artist-poet Gerald Malanga. The EPI’s influence can be felt in art/pop collisions ever since, from Lady Gaga to Kraftwerk’s performance of all their albums at Moma in New York this spring. Later this month, an art-rock festival in Cologne, Week-End, will feature visuals by David Shrigley, while Stephen Malkmus tops the bill, covering Can’s album Ege Bamyasi.

Certainly, the number of musicians who went to art school is vast, from Malcolm McLaren, who saw his management of the Sex Pistols as a continuation of the situationism he had imbibed at Central Saint Martins, to Brian Eno, three-quarters of the Clash and Jarvis Cocker. Pete Townshend was taught by Gustav Metzger, whose theories of autodestructive art influenced Townshend’s guitar-smashing.

Most of these bands applied their art-school training to their music, but the proccess can work the other way around, too. Elizabeth Price studied at the Ruskin school of fine art, co-founded quintessential 80s indie band Tallulah Gosh and is now nominated for this year’s Turner prize. Artist Sue Tompkins formed the band Life Without Buildings at Glasgow School of Art before leaving in alarm at the prospect of endless pub gigs and printing up T-shirts. Yet the things she learned as the band’s frontwoman have influenced her artwork, some of which is poetry and lyrics-based. “I get asked to participate in galleries but also a performance in a pub or a poetry night,” she says. “There’s a mix.”

Perhaps the most powerful reason for an artist to make music is its direct appeal to the emotions, and the body; art – particularly conceptual art – is more cerebral. “When I’m making videos or artworks it’s aspiring to the condition of music,” says Mark Leckey, another Turner winner, who has made records under the names donAteller, Jack Too Jack and Genital Panic, ranging from covers of rave classics, such as Dominator by Human Resource, to abstract soundscapes recorded on the streets of Soho. “So I inevitably end up making music. With art, there’s always an intellectual barrier. Music has a directness and a physical effect. Contemporary art comes from a conceptual idea and it can be returned to a conceptual idea. It can stay in the realm of language, of text, and there’s something about music that escapes that.” Leckey says he listens to two records – Trip II the Moon by Acen and Roadrunner by Jonathan Richman – before he sets out to create an artwork. “If I could achieve in some way what they achieve to me, then I’d be very happy.”

Are visual artists jealous of musicians? “Oh my God, yes,” says Frances Stark, an LA-based artist and former member of the band Layer Cake. Even the cubists’ collages of musical instruments, she says, are more interesting than truly moving: “What music does is, like, 10,000 times [more effective].”

But does being brilliant at one art form mean you can transfer those skills to another? “It tends to be more successful when it’s part of a considered project,” says Shrigley. “Martin Creed’s stuff is really great, and consistent with his project as an artist. But Yoko Ono made one good track – Why Not [on Plastic Ono Band] – and the rest’s rubbish.” Shrigley used to be in a band, but says he will stick to making spoken-word records. Making music, he says, “would smack of some kind of middle-aged vanity and desperation, and I’m keen to avoid that scenario”.

This touches on a final, more superficial reason artists make records – to plunge into a more glamorous and high-octane world than that of the studio and the gallery. It may be unfair to suggest that this was what motivated Hirst to get involved with Fat Les in 1998 (other members: Keith Allen and Alex James), but he certainly gave that impression. Perhaps some of the artists involved in today’s Gangnam Style tribute will have similar motivations. Ultimately, however, their aim is to show support for a fellow artist in the most mainstream way possible, using one of culture’s most potent and endlessly adaptable weapons: the power of pop.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.