There is a self-portrait in this exhilarating show of the artist naked and bleeding on an operating table. A nurse holds a bowl overflowing with blood and a vast stain is spreading through the sheets. Not one but three surgeons are in attendance and dozens of students are observing the agonies through the theatre window: witnesses, as we are, to the artist’s martyrdom.

It’s a ludicrous picture if you’re a stickler for the facts. Rejected by his lover, Tulla Larsen, Munch had turned a gun on himself during a final row, strategically missing everything except a finger of his non-painting hand. There was no need for major surgery. The picture is a performance, a public J’accuse made for display in an Oslo gallery where everyone, including Larsen and the press, could see it.

It is exactly what you might expect from Munch, that exuberant old miserabilist – exaggeration in the service of truth.

At Tate Modern, Larsen is also portrayed as a murderess in a bloody chamber or a vampire in the night; Munch as a stabbed corpse on a couch, one arm dangling lifelessly over the side like Marat in David’s great funeral portrait. The image is as transparent as a propaganda poster and equally one-sided, but who doesn’t recognise the potency of its feeling?

You stabbed me in the back, you ruined my life, you ripped out my heart! There’s rarely any need for titles, though the paintings frequently invite comic captions. Munch finds pictorial rhetoric for each expression, making the metaphors visual, not to say literal. That stain on the hospital sheets actually has the shape of a human heart removed from the body; but it also resembles something more piquant and personal: the shrieking face in The Scream.

Go and see this show if you possibly can. The bad times are always good with Edvard Munch. He has no shame when it comes to self-pity, hypochondria, jealousy or grief, is never too proud to confess to lust or depression. He is the friend who doesn’t censor the story as the rest of us might, doesn’t pretend to resignation or serenity or forgiveness. His emotions are open and energetically direct. His art is frankly invigorating.

Partly this is to do with its ardent theatricality. The 60 and more paintings in this exhibition are larger than one ever expects, and declare their meanings with such graphic force and clarity that one never wonders what’s happening on stage. The hell of a loveless relationship, the misery of solitude, the magnetic power of sex, or the dread of it: you know what this is like, you understand how this feels, this could be any of us. This is the underlying principle, and presumption, of Munch’s work.

So hyperbole becomes a means to universal truth, with the artist performing for the rest of us: lonely, ill, inebriated, foolish, stricken with Spanish flu, spurned by his lover, losing his wits or his eyesight. The self-portraits account for more than half this show, and though Munch’s exaggerations can be comic – think of the little screamer, hands held to face as if edified by a particularly scandalous piece of gossip – there is no reason to believe they are insincere.

Motherless by the age of five, victimised by a hellfire nutcase of a father who forced him out of bed at midnight to watch the death of his closest sister, he was an alcoholic who endured two nervous breakdowns and a lifetime of suffering and dread. Munch is an artist fit for the 19th century, parading his wounds on our behalf.

Except that he did not die until 1944. Three-quarters of Munch’s work was made in the 20th century, including several versions of The Scream and The Sick Child, which is not in fact a portrait of his sister but another child altogether. The object of this bracingly revisionist show is to modernise Munch, clear away the biographical interpretations that barnacle his work and draw him into the modernist century.

Munch worked in series, and in multiple media; quoted himself from one picture to the next; introduced the vocabulary of film to his art. The Modern Eye shows how advances in photography, cinema and lighting design influenced his work, what he may have taken from Degas, Caillebotte and the Japanese prints he saw in Paris (predictably, sharply receding angles and flattened space). The catalogue may be in danger of making a postmodernist of him, but it’s good to have the curatorial focus on the art, not the anguish.

Munch’s compositions are dizzying: bridges sheering away into the distance, figures rushing towards us like trains from a tunnel, bodies felled like trees in a wood. The works are grouped by pictorial idea. Tate Modern has the different versions of The Sick Child, where the paint itself appears to be weeping, or bleary, or dead as dust, each time matched to the emotion, so that one sees that Munch’s notorious repetitions are experimental, not merely commercial.

But what the show seems to bypass is the source of his longevity, what keeps Munch modern even when his subjects are syphilitic drinkers in wing collars or hair-tearing Medusas in long black frocks. And this is to do with his extraordinary gift for coining both archetypes and shapes.

The lone figure on a bridge, outlined by violent radio waves; the solid block of lovers bound by fatal attraction; the worm, the amoeba, the keyhole, the diamond-shaped face with punctuation-mark eyes; the shadows that leak from naked bodies like spreading stains. You would recognise them anywhere, along with the gorgeous colours and that distinctive alternation of brusque and fluid brushwork.

None of this is beyond parody, particularly not the yowling face; indeed it’s hard to tell what Munch meant by reprising that shape in On the Operating Table, if not some kind of joke.

But look at Weeping Woman – or rather the 10 weeping women at Tate Modern – a nude with eyes concealed and head hanging. It’s a weak image not because Munch paints it badly, though there’s a quavering in the brushwork that doesn’t come across as passive-aggressive (one of Munch’s singular strengths). The woman is just a conventional nude – there’s no symbolic form or psychological charge. The painting could be by anyone.

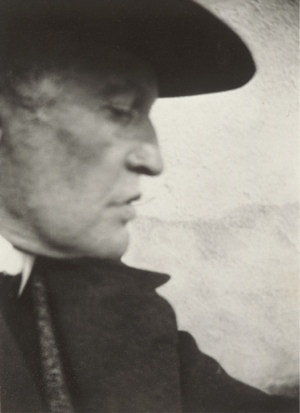

And Munch’s photographs, over-represented here, are equally banal and anonymous. Indeed these mechanical images – especially the over-exposed home movies of the artist lurking among the ivy – seem to push him further back into the 19th century than ever, like hearing Tennyson reciting “The Charge of the Light Brigade” on the newfangled phonograph.

“Photography,” Munch wrote, “will never compete with painting so long as the camera cannot be used in heaven or in hell.” The jealous man in his green and yellow bedroom, an open door revealing a kissing couple that could be imaginary or real; the trio of zombies in Death Room, so bereaved they might as well be dead themselves; blood in the snow, black claustrophobia, buzzing exhaustion and paranoia: his paintings always show far more than the lens can ever reveal.

The longest struggle of Munch’s life was against the dread of extinction that overshadows our days, and it produced his greatest masterpiece, Between the Clock and the Bed. The artist is seen in his late stance, legs planted, arms dangling by his sides, walled in between the high clock and the narrow bed, both by now heralds of death. As a depiction of an old man straining to remain upright it is incomparably poignant – no need for exaggeration: life and art are one at last – and also heroic. There is courage in Munch’s desolation, universal and inspiring. It’s a superb end to this show.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.