I accidentally scared a gallery technician witless while exploring the Hayward Gallery’s exhibition of invisible art. I was standing in a room of thick, velvety darkness. A technician pushed through the black curtains and became aware of someone else in the gloom. Apparently spooked, he asked: “Who’s that?”

It was a relief to see someone else scared, because The Ghost of James Lee Byars already had me seriously unnerved. This work of art consists of no more than its six-word title and a darkened room. Yet its atmosphere is palpable. Six words are enough to tell a hell of a ghost story, it turns out.

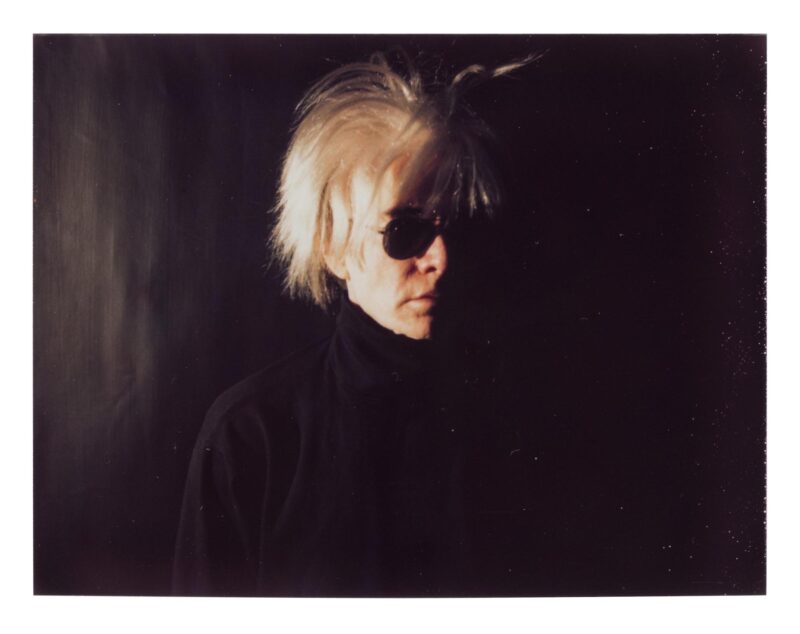

The American artist James Lee Byars conceived this freak-out in 1969. An enigmatic and morbid storyteller, he imagined his own death, not just in this work but in pieces with the resonant titles This is the Ghost of James Lee Byars Calling, and The Perfect Death of James Lee Byars.

Eventually, in reality, he died in Cairo in 1997. Judging by the terror it can inflict on Hayward contractors, I would guess the invisible image of Byars is creating quite a folklore behind the scenes.

Or perhaps they are dreading the critics. What, eight quid for a gallery full of invisible paintings? This exhibition courts tabloid headlines and bluff empirical sarcasm. It is, like Jerry Seinfeld’s sitcom, a show about nothing. But it succeeds because it is in on the joke, which it makes unexpectedly profound. Quite frankly, there is more art here, despite it being invisible, than in a lot of stuff galleries lure us to see.

There are indeed some invisible paintings in the show, white surfaces marked with materials that include “Brainwaves” by the Swiss artist Bruno Jakob. There is a drawing that fills a huge gallery and yet is almost impossible to find since the Taiwanese artist Lai Chih-Sheng has traced all the lines along floor tiles, corners of walls and fittings to make a drawing that is a near-invisible web-like echo of the place.

Yet the real heart of the exhibition is not so much in works that are barely there as in the thing they allude to, the unseen itself. As you put on a surreal buzzing headpiece to negotiate Jeppe Hein’s invisible maze or speculate on which gallery-goer may be the actor hired by Bethan Huws to behave just like a visitor, the notion of a world beyond appearances takes on a strange and powerful reality.

This exhibition is a seriously brilliant jest. It is a genuine history of an idea in art, a fascination with the immaterial and imperceivable that can be traced back to the audacious claims of Yves Klein in late 1950s Paris to create invisible atmospheres and “air architecture”, most famously in his 1958 exhibition of nothing, The Void. But it is also an absurd story. Carsten Holler exhibits an invisible car, one of a field of futuristic vehicles he designed for a utopian race. There is its starting place, painted on the gallery floor. But the supercar, called The Invisible, is for you to imagine.

The magic of the exhibition, its bizarre inversion of gallery-going, is that you do indeed imagine it. The car seems to be there. You don’t step on its starting block, in case you scratch the unseen paintwork.

Nearby is an empty white plinth. The air above it is cursed. The artist Tom Friedman got a witch to curse a zone hovering above the pedestal. As soon as you know this you do not want to put your hand into that evil space.

Why? Because nothing demands something of us. The human mind fills blanks with images and ideas; that is what a ghost story is, a way of filling darkness. This exhibition reveals that when artists, from Klein to Chris Burden, who hid himself on an elevated shelf in a gallery in 1975, started to deny that art had to be seen, they opened up a theatre for the imagination.

In the Hayward Gallery, the ghost of Byars haunts The Ghost of James Lee Byars. The visible world, as Plato pointed out, is a veil concealing truth.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.