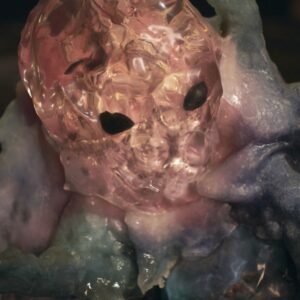

Mask II by Ron Mueck, 2001-2: ‘The head, innocently dozing on its plinth, calls forth one’s tenderness.’ Photograph: © Anthony d’Offay

There is a man at the door of this marvellous show who makes everyone jump. He seems to have been waiting in the shadows. Small, wiry, with blue eyes and a distinctive rake-over, he looks both familiar and strangely disapproving – as well he might, for this is the sculptor Henry Moore to the life.

Moore the maker of semi-abstract monuments, the arch-modernist who deplored the very idea of portrait sculpture: it’s a good joke to make him the host of the party, especially as a lifesize waxwork. But there is more to this than comedy. For you have to meet Moore’s gaze to get past him, and in that unnerving instant a shudder runs through you. It sets the whole tenor of the show.

Presence is a terrific gathering of people carved, cast, modelled in clay or turned to stone. It has bronze soldiers, marble statesmen, porcelain children and plaster mummies, ivory figurines and huge resin heads. There are lifelike portraits, posthumous portraits, invented portraits and semi-figurative sculptures that might have satisfied Moore, by Alberto Giacometti and Hans Arp.

The real as opposed to the ideal, the lifelike vignette against the marmoreal statue, the effect of colour, scale, clothes or glass eyes: all sorts of ideas are kept in play. But what unites all these sculptures is exactly what the show’s title alludes to – their curious and even sensational presence.

Waxworks, wooden effigies, hyper-real giants: figuration is a vigorous strain of contemporary sculpture from Antony Gormley and Ana Maria Pacheco to Juan Muñoz and Ron Mueck. But Mueck is the only one who qualifies as an old-fashioned portraitist; or rather self-portraitist, in the case of his own massive sleeping head.

Mask II has the look of life itself, down to the faint sheen of sweat. But walk round the back and the hollow mould is exposed, as if to say that this artifice is only skin-deep. And still the head, innocently dozing on its plinth, calls forth one’s tenderness. This is an object with presence.

A sculpture portrays a sitter quite differently than a picture; its presence comes, in part, from being bodied forth in the full dimensions of life, from space in the same way as real people. That gives it, so to speak, a head start. But not the least fascination of Presence is how such objects come to resemble portraits in the first place, and how they get this potent look of life.

Take the startling portrait that opens the show: an ancient bronze head dug out of the Libyan sands. Two thousand years ago, this youth had copper-plated lips, bone teeth and eye sockets fitted with glinting enamel. He must have looked so alive. But even now he has the vitality of character. High cheekbones and large eyes veer towards classical ideals, but the slightly weak chin and wry expression tug him back towards portraiture. He looks like somebody living, what’s more; he looks like Chris Martin of Coldplay.

Ever since Pygmalion, sculptors have tried to bring their creations to life. A head turn or an open mouth may counter the stasis of marble. Clay can look as pliable as living flesh. Mueck does it with special effects where one can hardly believe one’s own eyes.

But look at the 18th-century bust of poet laureate Colley Cibber, quite clearly a plaster effigy with coloured eyes and detachable hat. The impression of being in the presence of a disarmingly cheerful soul is amazingly vivid. The portrait pushes some essential life-likeness button while remaining conspicuously artificial; it is not just a matter of suspending disbelief.

Nor is factual truth the route to a perfect portrait. This show has a fine celebrity cast – Shakespeare, Lord Chesterfield, Jemmy Wood, the Gloucester banker said to have inspired Ebenezeer Scrooge – but only one of them appears in exact facsimile.

The death mask of Sir Thomas Lawrence, still with its Regency sideburns, is in some sense analogous to a photograph as a document of physical fact, warts and all. And yet it lacks presence. Prone on his plaster pillow, Lawrence looks less than real, and certainly less than himself; only art can make him into a portrait.

A subtle history of portrait sculpture emerges through this show. Before photography, sculptures were more easily reproduced than paintings, so heroes were cast – and recast – in economy editions. Shakespeare leans on a porcelain stump in Arden, the lines on his scroll available in German or English. Or you could buy him as a terracotta version of the earringed Chandos portrait, with or without goatee, a triumphant fiction to match all those blind marble Homers.

There are fashions in eyes, whether to indent or inlay, whether to include a hint of pupil or leave the eyeball a blank. Hair styling changes from Walnut Whip whirls to rippling incisions and those buns that sit on the head exactly like their real counterparts. Warts come and go (notably on the same eminent Victorian in two radically different portraits).

Heads are hewn out of stone, appearing monumental even when smaller than life; or modelled in clay that’s still quick with the maker’s mark. They aspire to the timelessness of statues or they attempt to overcome it with a glittering eye or a touch of blusher to the cheek.

Daphne Wright’s recent double portrait of her sons, eyes tight shut, shoulders hunched, records the physical discomfort of sitting for a full body cast. The two boys, sawn off above the elbow, appear immured in the plinth – suffering, as it were, for their mother’s art.

Ancient in its look of cold white marble, modern in its highly sophisticated casting, this sculpture arouses strongly protective emotions. It’s as if the children were trapped between life and death. Wright’s sculpture has a power no less primitive than the waxwork of Henry Moore, but considerably more metaphysical.

This is a terrific show, original, inventive and as stimulating as one might expect from Alexander Sturgis, late of the National Gallery, now director of the Holburne Museum, who believes, as few other curators of our times, that art might be about ideas as well as images. It is, moreover, about as good a survey of figurative sculpture as you could get – and if you can’t get to Bath, there’s an excellent book.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.