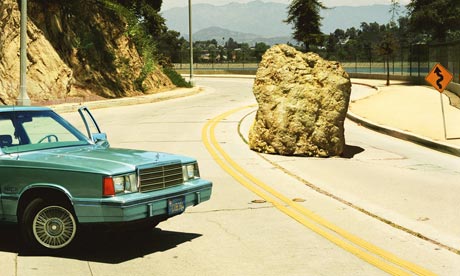

Alex Prager’s photographs ‘exude a sense of unreality’: 1.18pm, Silverlake Drive, 2012. Photograph: © Alex Prager; courtesy of Michael Hoppen

Both Stan Douglas and Alex Prager make elaborately staged photographs that look like film stills. They both use photography to create oblique fictional narratives that baffle and intrigue. It’s left to the viewer to figure out the bigger picture from the various references – cinematic and literary as well as photographic – embedded in the images.

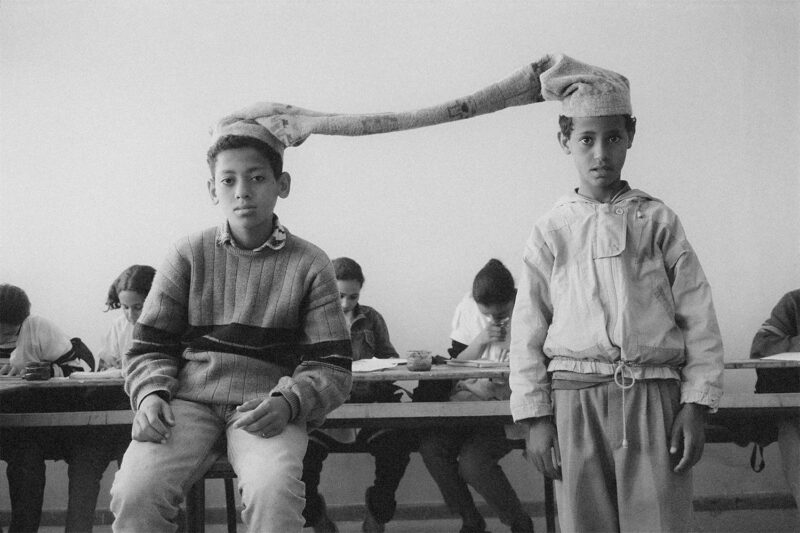

Stan Douglas, who lives and works in Vancouver, is the more cerebral artist, and over 30-odd years his films and photographs have touched on issues of race, politics and the vexed nature of representation. His new series of more than 40 black-and-white images is often challenging to the point of mystifying and you may, like me, leave this show questioning and requestioning its underlying meaning.

The conceptual premise of Midcentury Studio is that the photographs were taken by an anonymous Vancouver-based photographer between 1945 and 1951. The real-life inspiration for Douglas’s character is the self-taught press photographer and muckraking journalist Raymond Munro, a native of Vancouver, who worked for a tabloid called the Weekly Flash in the 1950s.

Many of the photographs seem like stills from a long-lost noir film: a brawl at a hockey game watched intently by a lipsticked femme fatale; a gangster in shades flanked in the back seat of a car by two plain-clothes cops; a dapper gent throwing dice in a gambling den. Elsewhere, a dual image shows a classic scam: a handshake between two men in which one deftly removes the other’s watch. What, though, to make of the triptych of images showing a hand gripping a cricket ball in various ways? Or the large-format freeze-frame of a cricket match in which, on closer inspection, the players are actually the same two actors, one black, one white, posed in different positions around the pitch?

The fact that Douglas is a black Canadian may have some bearing here, but race, like every other subtext in his work, is treated indirectly. If there is an over-riding narrative here it’s hard to follow, and intentionally so. We’re told that: “Douglas often presents his work in such a way that there is an element of chance and random ordering, meaning that the viewer can enter the narrative at any point and create their own understanding.” Maybe so, but that narrative, like the individual meanings of the photographs, remains frustratingly elusive. I found myself longing to see the imaginary film from which these stills are culled. For all their opaqueness, once seen, these strange photographic elaborations do linger in the mind, nagging away at one’s imagination.

Across London, at Michael Hoppen in Chelsea, the young Californian Alex Prager is also playing games with photographic history and representation. Her reference point is often the work of other photographers (in the past, she has even referenced the work of Stan Douglas, which gives some indication of the incestuous nature of a certain strain of ultra-postmodern conceptual photography). Here, Prager’s most obvious touchstone is the Mexican ambulance-chaser Enrique Metinides, whose brightly coloured crime-scene photographs are both gruesome and artful.

In one homage to Metinides, a smartly dressed woman hangs precariously on a pylon against a bright blue Californian sky. In another, a young woman lies across a network of electrical wires while an audience of silhouetted onlookers waits expectantly below. These images are elaborately constructed using cranes and winches that are then edited out using Photoshop in post-production. The end result is Metinides minus the real-life drama and tragedy.

Elsewhere, a photograph of a burning house in a field echoes Joel Sternfeld’s famous photograph of burning house in a field, though here the sense of unreality is such that the house looks like a model. The picture possesses none of the poignancy of Sternfeld’s complex image, in which a fireman purchases a pumpkin from a roadside stall while the house blazes in the background. In Prager’s version there is no context, no real sense of drama. It depends for its effect entirely on the viewer’s knowledge of Sternfeld’s photograph.

All the photographs in the Compulsion series exude this sense of unreality to one degree or another. It may be a comment on the media-fuelled sense of unreality that (if certain film-makers and writers are to be believed) holds sway in Prager’s native Los Angeles. There is certainly a Lynchian undertow throughout; if these images had a soundtrack, “Blue Velvet” would be on it.

Several images tend towards the cinematically apocalyptic – people floating in an oily green sea, a woman hanging from a falling car. Others, like the one of a woman falling from the sky (she was actually photographed while bouncing wildly on a trampoline), could be outtakes from a fashion shoot. As a signal of her intent, Prager has prefaced the accompanying catalogue with a short artist’s statement: “Mother Nature has always been stronger than us. Good and Evil have always contended. And there has always been the compulsion to watch.”

As if to ram home that point, the meticulously created scenarios are punctuated by composite photographs made up of close-ups of human eyes. The surrealists spring to mind as well as, again, Lynch, Hitchcock and the countless haunted protagonists of vintage Hollywood noir films and B-movies. A peculiarly Californian kind of vision, then, and one that comes with its own short film, La Petite Mort, complete with Gary Oldman voiceover, to be screened in the gallery.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.