Jeremy Deller: Joy in People from Stephen Pook on Vimeo.

A small figure in an oversized Flowered Up T-shirt dances around the rim of a dark and very fetid cave. “Shit!” says Jeremy Deller. “Woah!” He ducks as the first bat rising from the crater crashes into him. In the silence of the Texan countryside, the stirring of millions of bats below ground is like the wind getting up. Then the occupants of the cave emerge in a spiralling column, rising into the sky like smoke.

There is lightning on the horizon, a storm coming in, and the flitter of bat wings sounds like a gentle rain on leaves. The bat detector haphazardly taped to the top of one of Deller’s three cameras makes a frantic squelching noise. “It’s a sort of electronic music, isn’t it?” says the Turner prize-winning artist delightedly, filming the sunset emergence of one of the largest gatherings of mammals in the world.

Apart from the bats, the biggest attraction in this desolate corner of Texas is the state’s largest live oak tree. On the road to Utopia, every vehicle is an enormous pickup. We pass a dead armadillo and stop in a metal shed for a hot taco lunch. It has been 38C (100F)for 100 days. Crows peck the eyes of a dead deer. Deller has travelled to these bone-dry creeks to gather footage for an “unbearable” 3D nature film, the climax to his new exhibition at the Hayward Gallery called Joy In People. Given that title, a bat film is a typically unexpected touch.

With his slight frame and darting, curious eyes, there is something of the elf about Deller. The 45-year-old plans to survive the week filming bats on a large tub of mixed nuts. The last time he was in the US he turned orange from drinking too much carrot juice. “I don’t really cook,” he says dryly. It is surprising that such an English eccentric is not only fond of America but owns a piece of it. He bought five acres near Death Valley for ,000. “I’ve got a skyscraper, an oil rig, helipad,” he says. A sly joke is never far away. He bought the land with his residency money from an American museum. He doesn’t know if the museum approved. But he did use it for art – a friend recorded a live album of banjo music there.

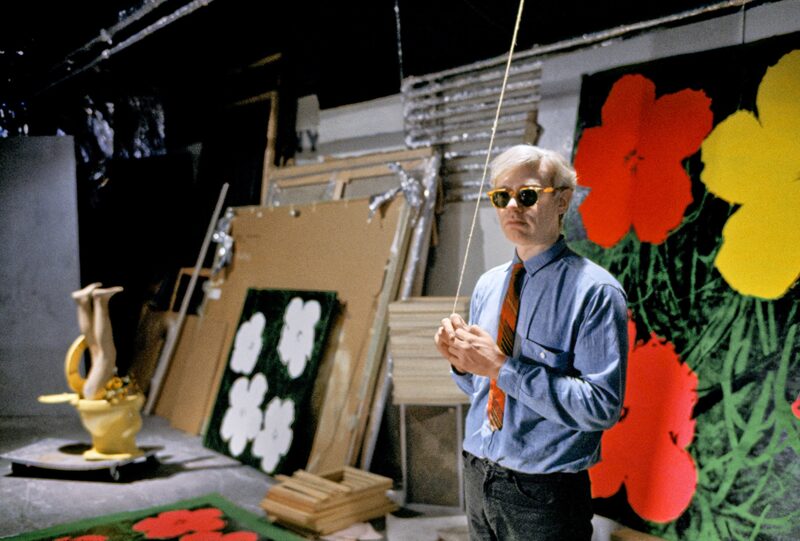

His life as an artist was awakened by an American: as a shy 20-year-old who hadn’t studied art, he met Andy Warhol at the Ritz on the artist’s last visit to Britain. “I was young, definitely, and relatively pretty,” says Deller. “When I met him in London, he said to me and my mate: ‘Oh you should come out to the Factory – we’re doing something for MTV.’ I thought, I’m actually going to take up this offer because this is never going to happen again. And so I did.” He hung out with Warhol in New York, gossiping, and saw that “you can create your own world, which is what he did. It was definitely a moment of clarity. I thought I would try to get by on my wits creatively, whatever that meant.”

When Deller was a child growing up in south London, his father, who worked in local government, would take him to galleries and museums. “When you go as a child, you’re not intimidated by it when you grow up. You just think it’s something that you can do,” he says. Deller studied history of art at university and then got a “small taste” of office work “nearly killed me”. So he lived at home for most of his 20s devising small-scale “interventions” – road signs on the streets commemorating Beatles manager Brian Epstein (about whom Deller had a curious fixation) and bumper stickers reading “I love joyriding” which he attached to a police car in Middlesbrough. His parents were baffled and Deller says he didn’t enjoy it at the time – his biggest success was selling his T-shirts declaring “My booze hell” and “My drug shame” in tabloid headlines at Covent Garden – but these years of “semi-employment” sound like a wellspring of creativity. “Everyone has the potential to be creative. It’s just having the time and the space. I don’t think artists are special. A lot of people do. That’s the great product of marketing artists – ‘they are different and special’. I don’t believe that. You see as much creativity outside the art world as inside it. I mean, all children are creative.”

Deller’s Hayward show, which he calls his “mid-career retrospective”, will celebrate this period with a recreation of his childhood bedroom and his first ever exhibition, held at home while his parents were on holiday. He has retrieved “all the crap” still lodged in his parents’ home; stuff under his old bed is now part of an exhibition. “It’s become official art now,” he says, amused. His life as art; it sounds like his Tracey Emin moment. “Sort of. Don’t say that,” he whispers sotto voce. “Horrible thought. I can’t bear her.” Can visitors bounce on your childhood bed? “Yes,” he says very decisively.

Deller’s breakthrough came in 1997, when he persuaded a brass band to perform house music. The result, Acid Brass, attracted loads of admirers (his favourite track was What Time Is Love? by KLF) “and I realised from then on, I can do this and I can do it the way I want to do it. I don’t have to make things any more, I can just work with people, and do these funny projects.” In 2001, Deller persuaded former miners and police to restage the “battle of Orgreave”, the seminal conflict in the miners’ strike, as if it were a medieval re-enactment. “Some people would just see that as wrong – to expect former miners to relive this terrible moment in their lives and in the history of mining in Britain. Often what I ask people to do might seem a bit, well, ‘wrong’ is probably the best word really, or slightly absurd. It’s the way you handle it that makes it OK. It’s very easy to exploit people, isn’t it? It’s one of the easiest things to do.”

For an artist known for his generous, collaborative approach, working with animals is “a tricky relationship”. Deller tries to “do things that aren’t exploitative even if the idea itself seems to be ridiculous or absurd, like the recreation of the battle in the miners’ strike,” he explains when we retreat from the bat cave to the porch of his log cabin. He sits in a rocking chair and I offer him a pack of repugnant beef jerky, hoping he might devour it “as I tear apart my peers, eating them alive”, nods Deller. Disappointingly, he is a recent convert to vegetariansim and has also vowed not to talk so freely about fellow artists after a Guardian interview a few years ago in which he slagged off both Emin and Damien Hirst. Only later I learn that Deller breaks his vegetarian vows in spectacular style at the Hog Pit, a Texan eatery favoured by the biker community.

Why bats? One evening Deller was watching School of Saatchi – a reality TV show in which Charles Saatchi set out to discover the next big thing. “There was some poor sod trying to cut a piece of wood and create a sculpture and I turned over to BBC1 and it was David Attenborough and time-lapse photography of sea anemones under Arctic ice. The art in that photography was so much more amazing than someone trying to create a crappy sculpture.”

Deller filmed the bats here once before as an unpredictable end to Memory Bucket, his 2003 film about Texas which became part of his Turner prize-winning exhibition, but was not happy with the results. He says he is “interested in the way they can co-exist pretty peacefully with each other. It’s incredible to live as close to other mammals. We can’t do it.” He wonders how well this explains his desire to make a better bat movie. “I do it because I can do it. I’m allowed to do it. A lot of art – or certainly what I do – is related to that; having an opportunity.”

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Deller has resisted the opportunity to make money. His work cannot be easily commodified. At times his projects seem almost wilful financial suicide. He lives in a modest flat on the grimy Holloway Road, north London, with his girlfriend, Tasha Amini, “a proper artist” – a painter. “There’s enough stuff in the world,” he says of churning out artistic objects. “I’m definitely more interested in ideas than I am in money. A disregard for money is always interesting.” Are contemporary artists too motivated by money? “Some are. And that’s a legacy of Andy Warhol.”

For someone who eschews commodification, his love of Warhol may seem odd but Deller argues a celebration of materialism was only part of Warhol’s legacy. “Because his art sells for so much, that’s all people can think of when they think of him now – money. Actually his legacy is about ideas.”

Deller venerates ideas. Part of his exhibition includes a section called My Failures – ideas that were never realised. These are variously silly (getting Iggy Pop to pose for life-drawing classes before a group of unsuspecting artists), brave (proposing a statue of Dr David Kelly looking as if he was about to jump from the fourth plinth at Trafalgar Square) and thought-provoking. “I like art that exists in people’s minds more so than it does in reality,” he says – art that people tell each other about. In the 1970s, the artist Chris Burden was shot in the arm with a gun as a piece of work. “I doubt if he made much money out of that but as an idea they don’t come much stronger, and you’ll never forget that I’ve told you that.”

Whether what Deller does is art, and where you find him in his work, troubles some critics. On a previous visit to America he toured the country with an Iraqi man, a US soldier and a car that had been blown up by a Baghdad bomb. This provocation must have created a great debate, especially when they pulled up at the rightwing college that hosts George W Bush’s library. Actually, says Deller, it was more a “conversation piece”. This is a characteristic choice of words. “Initially we were terrified we were going to get shot or lynched,” he says. But the most grief he got was from anti-war protesters who demanded he make explicitly political statements with the bombed car. “We wanted to make it more neutral so anyone could talk to us and didn’t feel like they were being used,” he says. “It’s almost a scientific experiment – what would happen if you added this car with these people to a trip around America? I was standing back and observing the reaction. I’m not necessarily in the middle of the work or getting in its way but I’m definitely on the edges of it, the fringes, seeing how it all goes.”

And so it is with the bats. While Deller records some sound, takes stills and edits the final film, the 3D shoot is undertaken by a group of quirky Americans. (“Our musician makes gothic music. Our voiceover man sounds like he is from a horror film. Our offices are black inside. We have a very alternative group of people,” says the 3D boss Greg Passmore, who arrives with two colleagues in a big RV, a pink-haired German and a pale-skinned young cameraman who looks like he might live in a bat cave.) Artists shape and sculpt things. Deller doesn’t. “I like that losing control of projects and letting people take some sort of ownership and get on with it in their own way. It doesn’t bother me. I’m not a control freak and I’m not a very technical person but maybe I’m a bit lazy as well.”

Deller resists “that old view of the artist being an exceptional person or a shaman” so strongly that some critics question whether he is an artist at all. He believes debates over whether his collaborations are art or not are a dull media preoccupation. “The public don’t mind. They are not interested. If something is good and interesting and they enjoy it … Whether it is ‘art’ or not is not really part of the conversation,” he says. “The public are ahead of the media.”

Deller has a knack for being perceptibly ahead of trends. A decade ago he was collaborating with the Women’s Institute, celebrating traditional craft skills and folk art. Now flower arranging, knitting and Keep Calm and Carry On needleworks are mainstream. The real world quickly catches up with Deller’s subversions. He once made a £250 cocktail at Stringfellows; now there are £35,000 cocktails on offer in London clubs. “If culture is keeping up with you it’s a kind of competition and I don’t mind that,” he says. His bat film fits into the current vogue for artists such as Björk and Chris Watson to produce work directly inspired by the natural world. “It’s not a terrible thing to be associated with,” says Deller agreeably.

Back in London, Deller sits in his flat editing the 3D bat film. From the first flashes of thousands of bats clinging to the cave roof, pink mouths opening like baby birds, it slowly builds into a visceral swarm in flight. The bats move so fast they look like an abstract pattern; even slowed down, their screams sound like Space Invaders. Towards the end of the seven-minute film, the emergence of bats slows, and a weird, restless tranquillity returns, just like the experience of this miraculous gathering of mammals in the wild. Deller wanted his film to be almost more than people could bear but is now having second thoughts. “You have to be very careful people aren’t going to be running out screaming after two minutes,” he says. “Kids will either really love it or it will traumatise them.”

After bats, Deller has a busy year ahead of him: he is producing a show for Bruce Lacey, an octogenarian artist from Norfolk and “total bohemian” who has led the kind of extraordinary life with a flagrant disregard for money that Deller approves of. He also wants to make a bench from a compacted Range Rover. It sounds like a very pointed piece of art but, true to form, he will leave people to work out for themselves what the bench comes from. Giving what he calls “a useless object” a “social function” is political, he reluctantly concedes, “because I hate those cars. If ever I’m going to be killed in London it is probably by someone driving a Range Rover because they are the worst drivers. The people who drive them obviously have some sort of personality problem. Usually they are on the phone at the same time as they are driving it. And not indicating. They are borderline psychopaths, I imagine.”

Jeremy Deller: Joy in People opens at the Hayward Gallery, London SE1 on 22 February and runs until 13 May 2012

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.